By Isabelle GerretsenFeatures correspondent@izzygerretsen

In a bid to reduce global electronic waste, Fairphone has created a smartphone that owners can repair themselves. What makes its technology so sustainable?

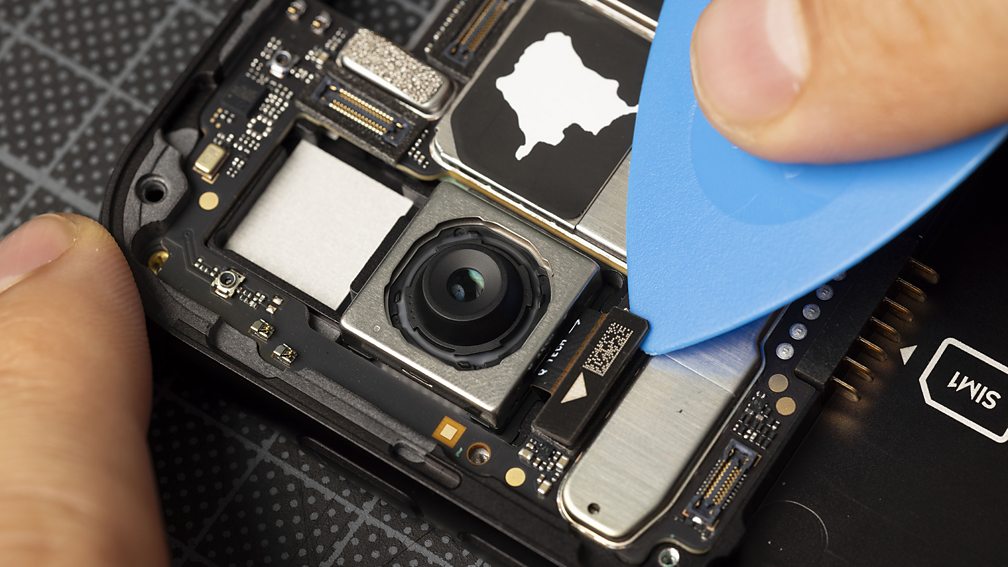

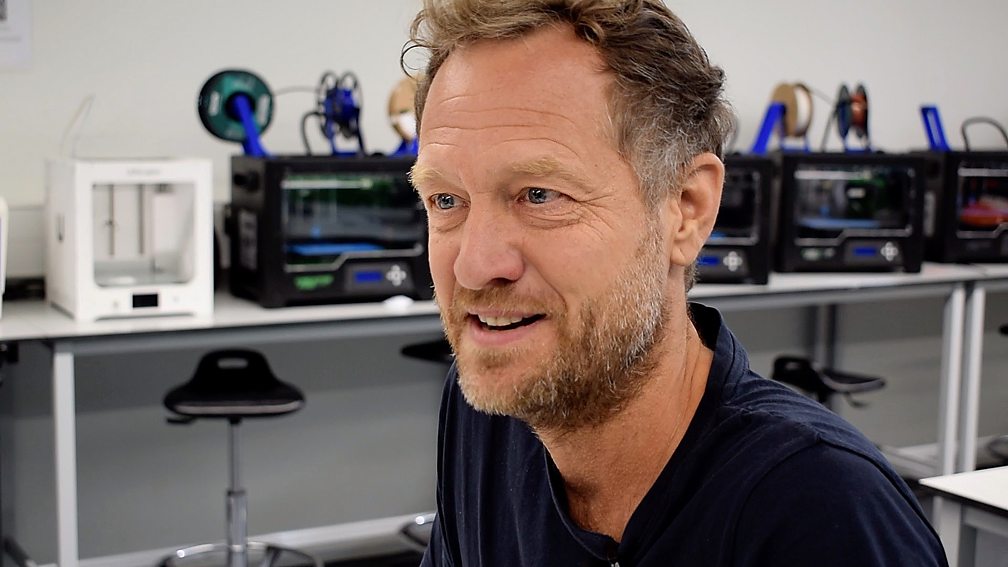

“This is my phone’s camera,” says Bas van Abel, holding a small, square component aloft. He has just removed it from his smartphone, using a tiny screwdriver.

“There’s eight components in total which can be removed and replaced,” he says, as he meticulously disassembles his entire smartphone, placing the camera alongside his phone battery, USB port, screen and loudspeaker.

Van Abel is the co-founder of the Dutch social enterprise Fairphone, which claims to have built “the world’s most sustainable smartphone”. But with a complex product containing rare metals and components from all over the world, just how sustainable can a smartphone be?

Founded in 2013 in Amsterdam, Fairphone makes Android smartphones which can easily be exchanged, customised and repaired by their owners. By enabling and encouraging people to fix their phones, rather than throwing them away as soon as a component breaks, Fairphone hopes to help reduce electronic waste.

E-waste is the world’s fastest-growing waste stream. An estimated 50 million tonnes of electronic waste is produced globally every year, weighing more than all of the commercial airliners ever made, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. Just 20% of that waste is recycled.

The mountain of e-waste is growing as the demand for portable devices and smartphones increases. By 2050, annual electronic waste production will more than double to 120 million tonnes, according to the World Economic Forum.

In 2022, 5.3 billion mobile phones were thrown away, the Belgian non-profit The WEEE Forum, which analyses electronic waste, estimates. In the US, people replace their phones every 18 months on average as new models with upgraded features are released. Most devices now come as sealed units that are extremely difficult and expensive to repair, or even produce error messages if damaged components are fixed.

Fairphone wants to break this trend by selling phones that have a longer working life.

“We make phones repairable so that you can use them for a very long time,” says van Abel. “It’s a very simple calculation: if you use the phone twice as long, you produce half the amount of phones and half the amount of waste.”

The Restart Project, a UK non-profit, estimates that increasing the lifespan of a smartphone by 33% could prevent carbon emissions equivalent to Ireland’s annual emissions.

You might also like:

Sustainability lies at the heart of Fairphone’s mission. “We use 100% recycled plastic in all our phones and fairtrade gold and silver,” says van Abel.

But not all the materials found in Fairphone models are sustainable. The Fairphone 5 contains 40 different materials, but only 14 materials (which make up 42% of the total weight of the phone) are sourced sustainably and ethically. Just 70% of those 14 raw materials come from fairtrade or recycled sources. The mining of rare earth elements used by Fairphone and other smartphone companies has a significant environmental impact and can result in the contamination of air, water and soil.

In an independent review of the company, experts said Fairphone could improve its sustainability credentials by procuring more materials from fair, certified sources and making phones that are upgradeable as well as repairable. Van Abel says Fairphone has expanded the number of materials it sources from sustainable and ethical sources from eight to 14, with plans to increase further.

“We focus on the 14 materials where we see the biggest need for improvement and the largest opportunities to benefit people and planet,” he says.

One of Fairphone’s ambitions is to improve ethical working conditions across the entire supply chain. The social enterprise began as an activism campaign in 2009, raising awareness around conflict minerals mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Today, Fairphone sources certified conflict-free tin and tantalum from mines in DRC and works with manufacturers to ensure fair working conditions in the mines and factories, says van Abel, adding that all workers are paid a living wage.

Despite its ambitions, Fairphone is still only a minor player in the mobile phone market – since launching, it has sold around 550,000 devices. To put this into context, more than 232 million iPhones were sold worldwide in 2022. But van Abel says Fairphone is trying to prove that it is possible for companies to turn a profit selling sustainable smartphones.

Sustainability, however, comes with a high price tag. The latest Fairphone model costs £649 (€699). This is partly because Fairphone has to build everything in-house, according to van Abel. “We do all the software updates ourselves as there’s not one company in the world that supports long-lasting phones,” he says. “There’s a lot of investment needed for us to be able to do what we want to.”

Fairphone’s repair scheme, however, is cheaper than its main competitors. A new battery for the Fairphone 5 costs £39.95 ($49), compared to the £80 ($99) fee Apple charges to replace an iPhone 15 battery and Samsung’s £109 ($135) fee for its Galaxy S23 phone. Replacing a Fairphone screen costs £89.95 ($112), compared to Apple’s £289 ($359) fee and Samsung’s £239 ($297) fee to get a new Galaxy S23 screen.

Fairphone also runs a recycling programme for smartphones which can no longer be repaired. Typically, however, just 30-50% of materials can be recovered in the recycling process, according to Fairphone. The company views recycling as a last resort.

“You want to reuse all the components,” says van Abel. “The last thing you want to do is recycle them…That’s why we focus so much on longevity.”

Like many modern electronic devices, smartphones are difficult to recycle as they contain up to 70 different elements. Slim, compact devices which are glued together are also difficult to pull apart in the recycling process.

“We’ve got an instinctive understanding that technology and electronics are not [made] to break down…that they are precious,” says Cat Drew, chief design officer at the Design Council in the UK, where she leads the sustainability initiative Design for Planet. “That’s why so many of us hold onto three or four old phones which might well belong in museums. We can’t bear to throw them away because we know that they are valuable.”

According to one industry estimate, as many as five billion mobile phones might be sitting unused in drawers around the world.

The design of most smartphones prevents people from repairing them and using them for as long as possible, says Drew. Phones aren’t designed in a modular, easy-to-disassemble way, she says, adding that people have a preference for very thin, sleek phones, which are difficult to take apart.

The cost of repairing electronics can also be “prohibitive”. “Getting a laptop screen fixed can be more expensive than getting a new laptop in the first place,” she says.

Building repairable smartphones is not a “technological challenge”, adds Joe Iles from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a non-profit which seeks to facilitate the transition to a circular economy where products and materials are reused and recycled as much as possible. The innovation to build repairable phones already exists and mainstream brands are starting to adopt it, he says. To date the sales model for devices such as smartphones has aimed to encourage consumers to update their devices every couple of years, often long before the lifespan they are designed for. New right to repair laws being introduced in Europe and the US are changing this.

In February, Nokia released its first smartphone which consumers can repair themselves, by swapping out broken parts using online repair guides. Apple has started publishing repairability manuals online and has opened a self-service repair store where consumers can buy Apple parts and buy or rent tools to help them fix broken devices.

But Apple’s repair scheme has been criticised for having extensive restrictions. Consumers must supply a unique serial number which is paired to an individual part of a device. The part cannot be replaced unless it is remotely paired to the device again using software provided by the manufacturer.

The real challenge is changing the business model of the electronics industry, says Iles.

“The way in which we make things, market and ship them…these supply chains have had decades of optimisation,” he says. “Breaking that [business model] or doing something that contradicts it is sometimes hard to imagine and hard for companies to actually invest in.”

Marketing is another hurdle. “The entire business model is based on growth and selling more phones,” says van Abel. “Marketing has been really good at selling us stuff we don’t really need.”

“A lot of people still get really excited about the release of a new phone,” Iles says, “but it is hugely wasteful to get a new one every year, just because the camera has a few more megapixels and the screen is slightly different size.”

There needs to be a business model in place that encourages people to repair their phones, Iles continues, adding that this could be achieved if companies offered consumers longer warranties on the electronics they buy or provided spare parts, such as batteries and screens.

Shifting to a subscription model for electronics could also incentivise technology companies to prioritise sustainability, says Drew. “It’s not about selling more and more, but about designing products that last and can be repaired.”

It is something already happening with clothing, she says, referring to the large number of rental platforms that are helping the fashion industry transition to a more circular economy. “Imagine if we did that for washing machines and for all sorts of different household items,” says Drew. (Read more about how to update your wardrobe sustainably.)

But doing this will require new laws and regulations to help “level the playing field” and ensure that companies continue to make a profit as they shift to a more sustainable model, says Drew.

Several European countries are already working to combat throwaway culture by making it easier for consumers to choose repairable products and get broken items fixed. In 2021, France started labelling certain electronic devices, including televisions, smartphones, washing machines, laptops and lawn mowers, with a repairability score based on five criteria assessing the price and availability of spare parts and how easily the product can be disassembled. In Sweden, people receive tax breaks for repairs on clothes and appliances including washing machines, dishwashers and bicycles.

In the US, there is also a push to encourage consumers to fix their devices.

President Joe Biden recently signed an executive order which aims to give US consumers the right to repair their own electronics. California, New York, Minnesota and Colorado all introduced right to repair legislation in 2023. The laws require manufacturers to provide consumers with the right tools and parts for seven years after production so that they can repair their own appliances.

“There is a lot of legislation coming out now that forces manufacturers to change their behaviour,” says van Abel, who hopes that Fairphone may inspire further changes in smartphone industry by showing what can be achieved. “Our primary goal is to make the entire smartphone industry more sustainable,” he continues. “We are raising awareness around problems in the supply chain and coming up with solutions.”

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

Credit: Source link