A woman or girl is killed

in Canada every 2.5 days. In a recent interview with Maclean’s magazine, Maryam Monsef, Canada’s minister for women and gender equality, called the problem of gender-based violence a “four-alarm fire.”

Gender-based violence happens everywhere, but certain places (like campuses, the military and RCMP) have especially high rates. And certain groups like women with disabilities and Indigenous women and girls face higher rates of violence.

Economically, gender-based violence costs the Canadian economy billions per year.

Gender-based violence is a “wicked social problem” that’s defined as difficult or impossible to solve because of its prevalence, cost, harm and complicated solutions. The immediate causes of gender-based violence stem from individual actions, but it is as much, or more, about what we believe and tolerate as a society.

To start shifting our shared narratives, I propose some new ways to think about gender-based violence.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/David Kawai

Change power dynamics

Gender-based violence is fundamentally about power — the power that individuals attempt to wield over one another, and that groups wield against other groups. At its root is the belief that one gender — men — should have dominance over others.

Historically, the subjugated gender has been women, but as the experiences of those who do not identify on the female-male binary are recognized, we are learning that it’s being not male that increases the risk of gender-based violence.

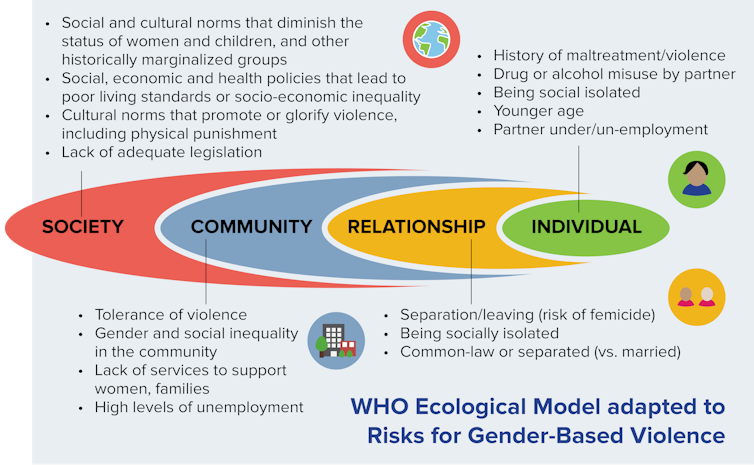

graphic by J. MacGregor.

While factors come into play on individual to societal levels, the causes of gender-based violence are rooted in the fact that women, children and those who don’t identify as male are not seen as fully human and deserving of human rights.

This means that to prevent gender-based violence in the first place, we need to shift the norms, beliefs and practices that ignore, or even encourage, these forms of violence in our homes, schools and workplaces.

Stop misogyny and victim blaming

There are two types of problematic beliefs about gender-based violence in Canada.

The first are myths, stereotypes and misunderstandings. These are usually based on outdated or false information, or ignorance of the scope and impact of gender-based violence.

While usually unintentional, these beliefs can cause harm. For example, a friend, family member or health care provider who says a woman should just leave her abusive partner doesn’t recognize that leaving an abusive relationship is often the time of greatest risk, including for murder.

The second kind of problematic belief stems from intentional messages to devalue and demean women and trans, queer, intersex and two-spirited people. These messages often include denigrating people’s experiences, victim-blaming, citing bad data and/or attacking data that doesn’t support the argument and claiming a crisis in false accusations against men.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

So-called men’s rights advocacy groups feature these beliefs. These views are closely aligned to more extreme narratives, including those of the “incel” movement, that increasingly lead to tragedies. These tragedies, like the Toronto van attack, not only kill people, but also shake our sense of safety and community.

Power structures in ‘intimate terrorism’

Researchers like Canadian criminologist Holly Johnson at the University of Ottawa have articulated concerns about the return of “an individualized and de-contextualized masculinist worldview” when it comes to gender-based violence. While feminists have built up arguments over the years that violence against women is about power, recent measurement trends have shifted this towards focusing on individuals.

Johnson argues that how we currently measure and report on gender-based violence amounts to “de-gendering violence.”

One focus of Johnson’s critique is the use of survey tools that conflate behaviours found in many poorly functioning relationships with abusive gender-based violence. This form of violence is almost exclusively perpetrated by men, most often against, and harmful to, women.

This conflation — for example when throwing something is counted the same as attempted strangulation — is what leads to some data, including current Canadian national surveys, showing equivalence between genders in overall intimate partner violence. When this occurs, the gendered nature of abuse is obscured.

Sociologist and gender-based violence researcher Michael Johnson calls these types of coercively controlling abusive relationships “intimate terrorism,” with patterns of physically, psychologically and sexually abusive acts used to establish dominance and control.

As noted in the above graphic, we need to take a social-ecological perspective on gender-based violence, modelled on one developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), in which risks and impacts are seen as multi-level.

The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2016 – A Focus on Family Violence in Canada; graphic by J. MacGregor

New data are coming

This fall, Statistics Canada and Women and Gender Equality Canada will start releasing new data from the national Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. Two other national surveys will then follow — one examining sexual violence on campus, and the other focused on workplaces.

The latter builds on extensive work by our team — the DV@Work Network — examining the impact of domestic/intimate partner violence on workers and workplaces. These findings have been used to advance legislation for paid and unpaid leave for survivors, and to reframe domestic violence as an occupational health and safety issue. We have produced a series of research-based infographics with key findings.

The new surveys ask better questions about how people identify their gender, ask about more types of violence, including new forms like cyberviolence, where and how violence happens, and crucially, to what effect — how does it harm, but also, how do people survive and thrive?

I’m excited about the potential of this more nuanced data to help us better understand and respond to the various and gendered ways that we use violence against one another.

Better data will mean better service design and delivery for anyone experiencing gender-based violence, regardless of gender.

To pretend that everyone experiences these traumas, and their effects, in the same way doesn’t help anyone. We have a unique opportunity to create compelling evidence-based narratives to dispel existing myths, and, importantly, to push back against the malicious and hateful messages designed to sow confusion and division.

[ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day. ]

Credit: Source link