Vladimir Putin spent a few pleasant hours this week with one of his friends and allies – an increasingly exclusive club these days. Putin met up with North Korea’s supreme leader, Respected Comrade Kim Jong-un, who rode his armoured train 20 hours to the Vostochny space centre in the remote Amur region in to talk weapons programmes with the Russian president.

Kim confirmed that Putin had his full support for Russia’s “sacred fight” against the west: “We will always stand with Russia on the anti-imperialist front”, he said as the pair posed for a joint statement after a trip to the cosmodome and a two-hour meeting. Details of what the pair spoke about have not been disclosed but issues are thought to have included North Korea supplying Russia with arms and ammunition in return for advanced satellite and nuclear-powered submarine technology.

As Daniel Salisbury, a visiting research fellow at King’s College London, has pointed out, it’s no secret that the two countries have been engaged in weapons transfers for some time. There is evidence of arms deals going back several years. And when Russian defence minister Sergei Shoigu was in Pyongyang recently, he was taken to an arms fair to look at the latest North Korean intercontinental ballistic missiles, long-range hypersonic missiles and advanced drones.

Since Vladimir Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine on February 24 2022, The Conversation has called upon some of the leading experts in international security, geopolitics and military tactics to help our readers understand the big issues. You can also subscribe to our fortnightly recap of expert analysis of the conflict in Ukraine.

Salisbury is concerned that any sanctions-busting deal between the two countries could not only help Russia on the battlefield in Ukraine, but could significantly boost North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction programme. Neither of these outcomes would be beneficial to international security.

Read more:

Ukraine war: two good reasons the world should worry about Russia’s arms purchases from North Korea

Ukraine is also urging its allies to step up supplies of weapons and according to reports from Washington the US president, Joe Biden, is close to reversing his stance on providing Kyiv with the long-range missiles systems it has been begging for. Biden was loath to provide Army Tactical Missile Systems, which have a range of up to 300kms, because of fears that Ukraine might use them against targets against Russia, with the prospect that might lead Putin to retaliate against Nato.

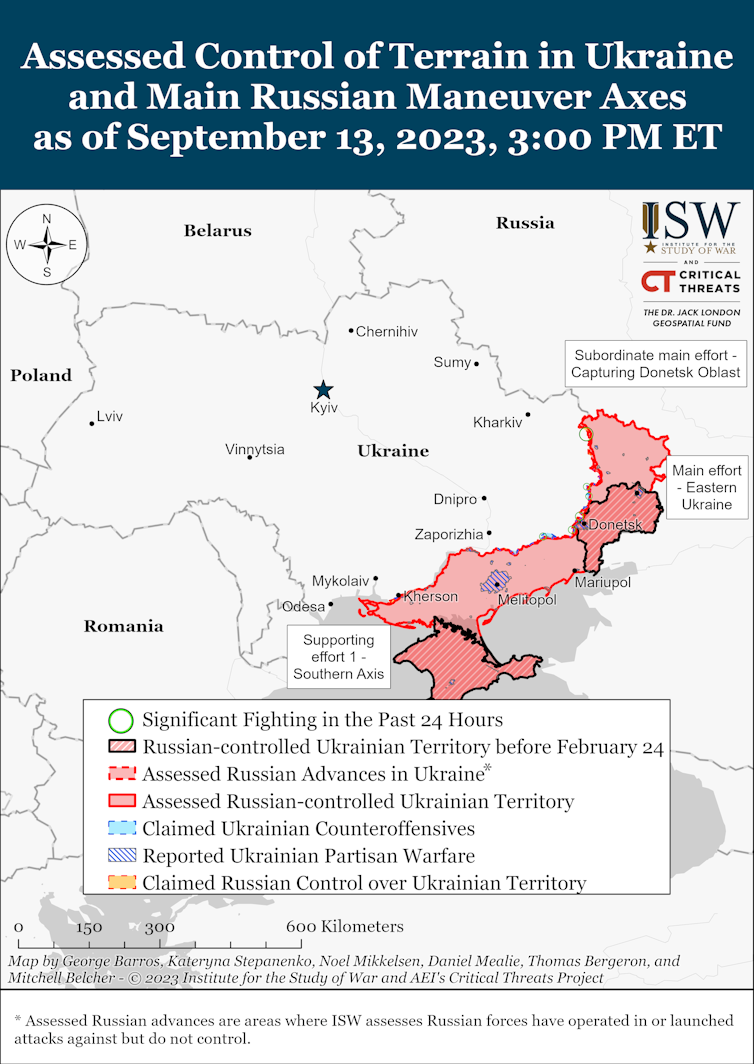

Institute for the Study of War

But Ukraine has been using home-grown drones to attack targets in Russia and there are signs that sentiment is shifting. This, writes professor of international relations and security at the University of Bradford Christoph Bluth, has a lot to do with the slow progress of Ukraine’s counteroffensive.

More western equipment – including weapons better suited to attacking targets in Russia’s “deep rear” – would undoubtedly help Ukrainian troops make the breakthroughs it needs to achieve its strategic aims, the most important of which is to drive southwards to the Sea of Azov and cut Russia’s land bridge to Crimea.

Read more:

Ukraine war: US and allies may supply longer-range missiles – how this would change the conflict

Ukraine has been supplied with UK-made Storm Shadow cruise missiles. And it’s believed to be a combination of these and unmanned boats that launched a successful attack on Russia’s naval facility at Sevastopol. The attack severely damaged two vessels, reportedly beyond repair: a large landing ship and a Kilo-class submarine.

As Gavin Hall – a teaching fellow in international security at the University of Strathclyde – notes, the attack on Sevastopol and a recent successful recapture of a number of oil and gas platforms off the coast of Crimea known as the “Boyko towers” will be considerable morale boosters, given the slow progress on the battlefield itself.

Read more:

Ukraine war: capture of key Black Sea outposts and strike on Crimea show Kyiv’s increasing confidence

The Storm Shadow missiles which Ukraine used against Sevastopol were developed as part of a joint venture between French manufacturer Matra and Britain’s BAE Systems. BAE, which has made a large proportion of the weapons supplied by the UK to Ukraine, recently announced its plan to set up branch business inside Ukraine.

As Martin Owens – a senior lecturer in international business at Sheffield Hallam University – notes, the company has done well out of the war, winning a record £21.1 billion of new orders in the first six months of 2023 alone.

Clearly, writes Owens, establishing a business in a country at war comes with considerable risk, and BAE will begin by establishing a a management office to coordinate sales and services with a view to setting up a manufacturing operation in Ukraine if all goes well.

Read more:

What BAE’s Ukraine deal shows about the risks and opportunities of setting up a business in a war zone

Playing politics

It may have been disappointing for western members of the G20, which met last weekend in New Delhi, to have to put their name to a declaration which failed to condemn Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. The corresponding statement made at the end of the 2022 summit in Bali, Indonesia last year was unequivocal, deploring “in the strongest terms” Russian aggression and demanding “its complete and unconditional withdrawal from the territory of Ukraine”.

But the statement emerging from the world leaders in New Delhi stopped short of that. It said all states must refrain from acting against the territorial integrity of other states and rules that use of nuclear weapons was “inadmissible”.

Jennifer Mathers, senior lecturer in international politics at Aberystwyth University, believes that this is a reflection of the growing clout of the global south, much of which sees climate change and inequality as more pressing issues than a war on the edge of Europe. She also believes that in agreeing to the wording, Biden was probably allowing Indian prime minister Narendra Modi a “win”, something to boost his stature as a counterbalance to China.

But she also believes Biden’s “soft diplomacy” by showing a degree of humility in this instance could be a sensible tactic which could in the long run help the US argue for more global unity around its opposition to Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Read more:

Ukraine war: why the G20 refused to condemn Russian aggression – and how that might change

From one bloc to another, EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has given her strongest indication yet that Ukraine and other countries – including the western Balkans, Georgia and Moldova – are under serious consideration for membership. Her annual state of the union speech on September 13 envisaged a “union complete with over 500 million people living in a free, democratic and prosperous” EU.

EPA-EFE/Julien Warnand

Nora Siklodi and Nándor Révész, who lecture in politics at the University of Portsmouth, give us their analysis of Von der Leyen’s speech, which appears to be signalling that she believes the EU ought to streamline its membership process to allow new members to join without lengthy debates or treaty changes.

Read more:

The signs that the EU has completely changed its perspective on adding new members since Russia invaded Ukraine

Meanwhile Russia pressed ahead with its local elections last weekend, including in some of the regions it occupied and annexed via “referemdums” last September which were characterised by a surprisingly high turnout and a near unanimous enthusiasm for joining Mother Russia. In the least surprising news this month, Putin’s United Russia Party did extremely well – unsurprising given most real opposition parties were banned from putting up candidates.

Stefan Wolff, an expert in international security from the University of Birmingham, and his writing partner Tetyana Malyarenko, a professor of international relations at the University of Odesa, point out that even by the Kremlin’s recent standards these polls were risible. Russia doesn’t even occupy large chunks of the annexed regions.

But they warn that this is all part of Putin’s playbook by which he plans to “Russify” the occupied territories. Electing a group of loyalists to do the Kremlin’s bidding in these areas aims to convey a sense of local participation without the risk of any real dissent, they write.

Read more:

Ukraine war: Russian-held elections seek to normalise illegal occupation and reveal reality of a long war ahead

Competing narratives

Of course, Putin has also gone out of his way to marginalise dissent in Russia in recent years. One of his targets as part of this mission has been Russia’s once-lively independent theatre scene that flourished after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since the invasion, many of its leading lights have lost their jobs, been jailed on dubious charges or been forced to leave the country.

Meanwhile, according to Julie Curtis, a professor of Russian literature at the University of Oxford, state subsidised theatre has become the vanguard of the new agitprop, parroting patriotic messages. As one exiled director bitterly comments: “There is currently one country which certainly is engaged in cancelling Russian culture. And that country is Russia itself.”

Read more:

How Russia’s theatre scene has been obliterated by Putin’s culture war

One episode from Russia history that seems unlikely to be the subject of a rousing patriotic drama is the disastrous Soviet-Polish war of 1919-20 when Lenin, emboldened by some battlefield successes in what is now generally referred to as the “Russian civil war”, decided to embark on a full-scale invasion of Poland.

According to historian Peter Whitewood of York St John University, Lenin’s plan was to “sovietise” Warsaw before pressing on to build a bridge through to Germany. It wasn’t to be: in what became known as the “Miracle on the Vistula”, Polish leader Józef Piłsudski routed the Russians.

Whitewood believes the parallels with Putin’s invasion of Ukraine are interesting. Putin’s main justification for sending Russia’s war machine into Ukraine last year was that Ukraine is a pawn in a dastardly US plan to encircle and dismember Russia.

In 1919, Lenin and much of the Bolshevik leadership believed that Poland’s strings were being pulled by capitalist western powers in the shape of Britain and France. As Winston Churchill once told the UK’s House of Commons: “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

Read more:

Russia’s disastrous decision to invade Poland in 1920 has parallels with Putin’s rhetoric over Ukraine

Ukraine Recap is available as a fortnightly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

Credit: Source link