This most recent rally was sparked by a confluence of global and market events, including the Russia-Ukraine war and uranium supply challenges related to conversion and enrichment.

The drive for nuclear energy to be a part of the fight to combat climate change is also having an oversized impact on the uranium price outlook as governments look to nuclear as a carbon-free energy source. Even Sweden is considering lifting its ban on uranium mining in an effort to support growth in it own nuclear power industry, for which it currently imports nuclear fuel.

“Sweden currently uses 2.4 million pounds U3O8 annually in its three nuclear power plants and has committed to building two additional nuclear reactors by 2035,” World Nuclear News reported.

Although prices have since pulled back to the US$78 to US$80 range as of mid-September, there are notable signals that the market may be in for plenty of upside to the uranium price forecast in the years ahead.

For many years, the uranium market’s back-and-forth struggle to move out of a rather entrenched trough had investors asking, “When will uranium prices go up?” Now that they have, the questions that remain are whether they are up enough to spur uranium mining activity and whether or not they have further to go.

Before we try to answer those questions, we’ll have a look at what’s moved the uranium spot price in the past, including the energy metal’s supply and demand dynamics.

How have uranium prices traded historically?

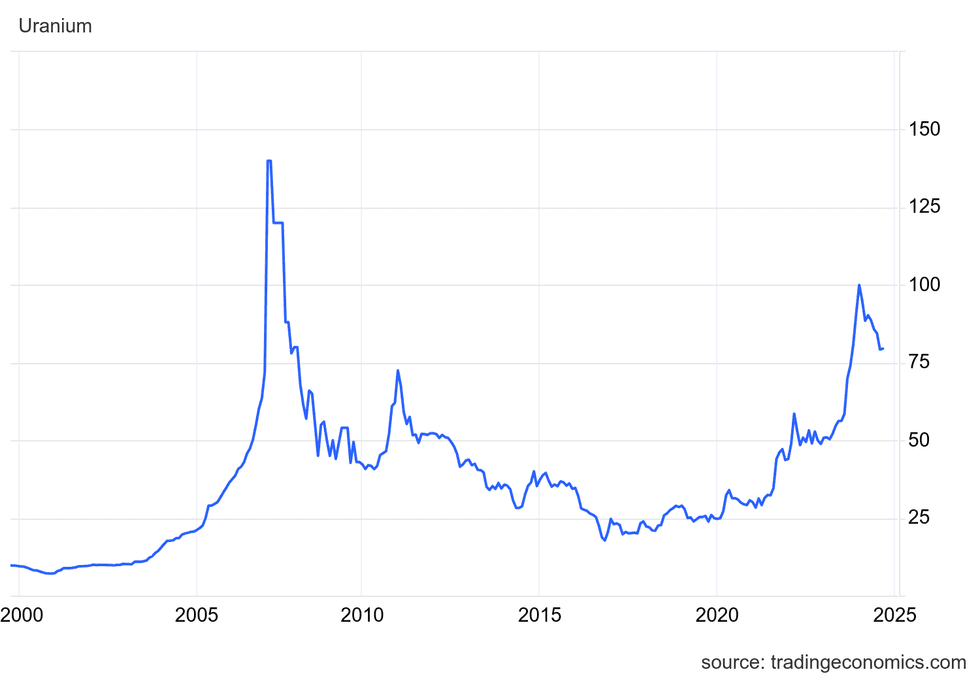

As briefly outlined above, uranium has experienced a wide price range this past century — while its highest level was nearly US$140, the lowest U3O8 spot price came in at just US$7.

In 2003, the price of uranium began an upward trend as demand for nuclear power rose alongside the world’s need for energy, especially in growth economies such as China and India. These increasing energy demands came at the same time as significant supply-side disruptions. For example, in 2006, Cameco’s massive Cigar Lake mine in Saskatchewan flooded, stalling production for several years at one of the largest uranium deposits in the world.

The inability to move this uranium ore to market was a huge setback for the uranium industry, and translated into explosive price growth for the metal in 2007. However, those impressive gains were soon undone by the 2008 economic crisis, which sent uranium on a downward spiral, slipping below the key US$50 level in early 2009 and to the US$40 range in 2010, as is shown in the uranium price chart below.

Uranium’s price history, 2000 to 2024.

Uranium price chart via Trading Economics.

At the start of 2011, uranium got a serious push to the upside along with other energy metals as the global economy began to recover. The tight supply situation, heightened by years of low prices, also played a part in pushing the spot price past the US$70 level.

The rally was short-lived, however, as Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster in March shook confidence in the sector. The uranium spot price began a slow slide to lows not seen since the start of the century, ultimately bottoming out at US$18 in November 2017.

Although COVID-19-induced supply disruptions at the world’s top uranium mines briefly sent the commodity to a four year high of US$33.93 in May 2020, it wasn’t until the fall of 2021 that uranium started to find its footing again.

In September 2021, uranium began to show signs of life as it shot up to a nine year high of US$50.80. The 2021 uranium price rally came after supply cuts from major producers, including Kazakhstan’s Kazatomprom and Canada’s Cameco( TSX:CCO,NYSE:CCJ), alongside the emergence of the launch of the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (TSX:U.UN).

Prices were soon see-sawing between US$38 and US$48 in October and November, but the start of 2022 brought civil unrest in Kazakhstan, as well as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. These events proved price positive for the uranium market, and by mid-April, uranium prices had reached an 11 year high of US$64.61.

Looking at the demand side, utility companies had once again returned to the table to sign new long-term uranium supply agreements to secure price and supply. This coincided with uranium supply challenges related to conversion and enrichment. The result was that from April 2021 to April 2022, the price of uranium soared by an eye-popping 106.47 percent.

By H2 2022, uranium prices had begun to slide back to the US$50 range. Much like the broader commodities market, uranium felt the squeeze of higher interest rates as central banks, including the US Federal Reserve, sought to curb rising inflation.

While the uranium price remained stuck in the low US$50s range for much of 2023’s first half, positive fundamentals born out of the view that nuclear energy is critical to reducing global carbon emissions sparked another major price rally beginning in the fall. By January 2024, as the uranium spot price hit US$106 per pound, many market analysts were loudly proclaiming that the next uranium bull market is finally here.

However, uranium prices went on to consolidate in Q2 2024 to the US$80 range, which many experts see as a natural part of the nuclear fuel’s emerging bull market cycle. Although the spot price has pulled back this year, the long-term contract price has increased. Term prices are considered by industry insiders to better reflect uranium market fundamentals.

What factors impact uranium supply and demand?

Uranium prices are mainly influenced by aboveground mine supply and demand for nuclear energy. To understand where those stand, investors in this sector typically look to:

- output from uranium mines

- the number of nuclear reactors online, under construction or planned

- the signing of long-term contracts between uranium suppliers and utilities companies

Analysts with a bullish lean believe the uranium market cycle has reached its bottom and that a break to the upside for uranium prices is supported by positive supply and demand fundamentals.

On the demand side, nuclear energy generated from 440 reactors around the globe supplies about 9 percent of the world’s energy requirements. Russia is constructing four with another 14 confirmed or planned, and India has seven nuclear reactors under construction. Meanwhile, China alone is constructing 30 new reactors at the moment. In fact, Bloomberg reported in August 2024 that the Chinese government is investing US$31 billion in building 11 new reactors across five sites over the next five years.

A World Nuclear Association (WNA) report forecasts that nuclear generation capacity will grow from 391 gigawatts electric (GWe) in 2023 to a total of 686 GWe in 2040. About 83,840 metric tons (MT) of uranium will be required to feed reactors in 2030, up significantly from the 65,650 MT of uranium required in 2023, according to the WNA’s uranium forecast. The firm projects that nearly 130,000 MT will be needed in 2040.

On the supply side, major uranium producers are still not producing at full capacity, and new uranium exploration and development projects are few and far between. The WNA points out that world uranium production dropped from 63,207 MT of uranium in 2016 to 47,731 MT of uranium in 2020. Although that figure ticked up slightly higher in 2021 to 47,808 MT and again in 2022 to 49,355 MT, the organization notes that only 74 percent of 2022’s reactor requirements were covered by primary uranium supply.

Huge cuts to global uranium production have come from Kazakhstan, the world’s largest uranium-producing country. Responsible for 43 percent of global uranium production, the Central Asian nation began reducing its annual production levels in 2018.

In its 2023 financial report, Kazakhstan’s state uranium firm Kazatomprom warned that it sees a major supply deficit in the uranium market post-2030. “In the current pricing environment, another Kazatomprom-sized supply source will be needed to cover future market needs,” said Kazatomprom CEO Meirzhan Yussupov.

In early 2024, the company reduced its production guidance for the year due to several challenges, including difficulties obtaining sulfuric acid.

However, after its H1 2024 production totals showed a 6 percent increase over total production in the same period last year, Kazatomprom increased its production guidance for the year from a range of 21,000 to 22,500 MT of uranium to the new guidance of 22,500 to 23,500 MT of uranium. The company’s sales guidance for 2024 remained unchanged.

Canada, Namibia, Australia and Uzbekistan are also among the world’s biggest uranium producers. In Canada, Cameco shuttered the Saskatchewan-based McArthur River mine in 2018 and temporarily closed Cigar Lake — the world’s top uranium mine — in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In November 2022, the mining giant brought the McArthur River/Key Lake operation back online.

In 2023, Cameco produced 17.6 million pounds of uranium, falling short of its original production target of 20.3 million pounds for the year. The company’s 2024 guidance is set at 22.4 million pounds. In its H1 2024 report, the company shared that production for the first half of the year had come in at 12.9 million pounds.

As for Australia, Boss Energy (ASX:BOE,OTCQX:BQSSF) announced in April 2024 that it had produced the first drum of uranium out of its Honeymoon project in South Australia as part of its commissioning process. The current mine plan only uses 36 million pounds of the project’s total JORC resource of 71.6 million pounds. Boss’ goal is to scale up production at Honeymoon to 2.45 million pounds of U3O8 per year.

In the US, Boss Energy began uranium production at its South Texas-based Alta Mesa in-situ recovery (ISR) central processing uranium plant in June 2024. “With operations now ramping up at both Honeymoon and Alta Mesa, we are on track to hit our combined nameplate production target of 3 million pounds of uranium per annum,” said Managing Director Duncan Craib.

Uranium Energy (NYSEAMERICAN:UEC) announced the restart of uranium production at its Wyoming-based Christensen Ranch ISR operations in August 2024. The first shipment of yellowcake from the mine is projected later in the year. Scott Melbye, executive vice president at UEC, told INN during a March 2024 interview that the Burke Hollow ISR project in Texas will be company’s next project to come online.

Despite this positive news, the WNA reports that supply deficits are likely to continue in the years ahead as current global production levels are not enough to meet forecasted demand.

“To meet the Reference Scenario requirements from early in the next decade, in addition to restarted idled mines, mines under development, planned mines and prospective mines, other new projects will need to be brought into production,” the WNA report states. “Considerable exploration, innovative techniques and timely investment will be required to turn these resources into refined uranium ready for nuclear fuel production within this timeframe.”

When will uranium prices go up?

So when can investors expect to see further gains in the uranium price? And how far can we expect uranium spot prices to climb?

A good gauge for which way the winds are blowing is utilities contracts, as these entities are traditionally the greatest sources of uranium demand. In fact, only about 10 to 15 percent of uranium trades happen on the spot market — the vast majority of uranium is sold through large long-term contracts between producers and utilities.

It’s also useful to watch the rest of the nuclear fuel cycle. Russia controls about 50 percent of global conversion and enrichment capacity — this dominance amid the country’s war with Ukraine has spiked prices for these services. Recent moves by the United States may impact this dominance. In mid-May 2024, Biden signed into law a US bill banning Russian uranium imports through the end of 2040.

Speaking to the Investing News Network in a June interview, Ben Finegold, director at Ocean Wall, referred to this as one of the most significant events for the uranium market since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“I think that we’re going to start to see a move much higher both in terms of term volume and in terms of term prices,” he said. “Fuel buyers have got the clarity that they need, particularly in the west now, on the US’ stance on the future procurement of Russian uranium.”

In the month following the launch of the ban on Russian uranium imports, the US Department of Energy announced plans to invest up to US$2.7 billion to stimulate the development of the country’s uranium enrichment capacity and nuclear fuel supply chain.

Not to be outdone, in September Russian President Vladimir Putin put forth the threat of limiting exports of uranium to western nations. The news gave a bump to the share prices of uranium miners such as NexGen Energy (TSX:NXE,NYSE:NXE), Cameco and Denison Mines (TSX:DML,NYSEAMERICAN:DNN).

Uranium stocks have languished in recent months as the winds have left the sails of uranium prices. But plenty of optimism remains for the sector. Speaking to INN in September 2024, Mart Wolbert, analyst at Contrarian Codex, shared his thoughts on supply and demand fundamentals in the uranium market, why uranium prices have dropped, if uranium stocks will go up and what’s next for prices.

Even though uranium spot prices have receded down around the US$80 level, Wolbert remains bullish on the market going forward and thinks higher prices could be in the cards. He points to the 42.5 million pounds that have been signed into long-term contracts this year, and advises uranium market watchers to look at term prices rather than spot as a truer indication of where the market is going.

As Reuters reports, long-term uranium prices are coming in at 16-year highs, and are expected to increase further. “With a stronger market environment, we’re currently locking in ceilings of about $125-130/lb and floors at about $70-75/lb in market-related contracts,” according to Cameco.

Looking over at spot uranium price prediction for 2025, as of mid September 2024, analysts at Trading Economics were forecasting that uranium would trade at US$82.60 in 12 month’s time.

This is an updated version of an article first published by the Investing News Network in 2020.

Don’t forget to follow us @INN_Resource for real-time updates!

Securities Disclosure: I, Melissa Pistilli, hold no direct investment interest in any company mentioned in this article.

Editorial Disclosure: The Investing News Network does not guarantee the accuracy or thoroughness of the information reported in the interviews it conducts. The opinions expressed in these interviews do not reflect the opinions of the Investing News Network and do not constitute investment advice. All readers are encouraged to perform their own due diligence.

Credit: Source link