The largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history began ten years ago, on April 20, 2010. A massive explosion killed 11 workers on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, and a blowout spewed more than 3 million barrels of oil from the Macondo well, located 70 miles off the coast of Louisiana.

For three months the oil company, BP, struggled to contain its runaway well, which it finally capped on July 12 and permanently sealed in mid-September. By that time, oil coated more than 1,000 miles of coastline in six states and covered over 40,000 square miles of the Gulf of Mexico.

This spill was the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history. After a dreadful start, BP and its drilling partners removed most of the oil from Gulf coast beaches over the next several years; the visible sheen of the oil slick eventually disappeared as well. But studies indicate that it will take parts of the Gulf, such as deep ocean ecosystems, decades to recover. We may never know the full extent of the ecological damage.

BP paid dearly for the reckless corporate culture of cost-cutting and excessive risk-taking that caused the spill: more than US$60 billion in criminal and civil penalties, natural resource damages, economic claims and cleanup costs. Indeed, from a legal standpoint, the legacy of the Gulf oil spill is the sheer size of the payout, which ushered in an era of multibillion dollar criminal and civil penalties for environmental and other corporate crimes.

In most other respects, however, the legal landscape governing offshore drilling is unchanged from before the spill. The U.S. still outsources drilling safety and spill cleanup to industry, which has proven far more adept at extracting oil than protecting the environment.

Meanwhile, Americans have yet to heed the spill’s wake-up call to reduce our nation’s dependence on fossil fuels and accelerate the transition to clean energy. From my perspective as an environmental law professor and the former chief of the Justice Department’s Environmental Crimes Section, that failure stands out as the continuing tragedy of the spill.

Holding BP accountable

BP endured years of costly litigation in the wake of the Gulf oil spill. In 2012 the company reached an agreement with the Justice Department to plead guilty to 14 criminal counts, including manslaughter, obstruction of Congress and violations of the Clean Water Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

The company paid a $4.5 billion dollar criminal penalty – the largest in U.S. history at that time. For comparison, the previous record was a $1.3 billion criminal fine paid by Pfizer for pharmaceutical fraud in 2009. The largest penalty for environmental crime was the $125 million fine imposed on Exxon for the Valdez oil spill in 1990.

In 2015 the Justice Department and Gulf coast states reached a record civil settlement with BP that totaled over $20 billion, including a $5.5 billion civil penalty under the Clean Water Act, $8.1 billion in natural resource damages and $5.9 billion in payments to state and local governments. BP also paid about $15 billion in cleanup costs and another $20 billion in economic damages to companies and individuals harmed by the spill.

Sean Gardner/Getty Images

The BP settlements set benchmarks that influenced the size of penalties imposed for subsequent corporate wrongdoing. Volkswagen paid more than $30 billion for the 2015 revelation that it cheated on diesel emission standards by rigging software in its cars. Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase have paid billions of dollars in fines since the 2008-2009 financial crisis for misconduct that included mortgage fraud.

BP was worth more than $180 billion at the time of the Gulf oil spill and is still one of the largest companies in the world. But it was on the brink of collapse after the spill, and few other companies could afford the costs BP incurred. From a corporate accountability and deterrence standpoint, the settlements were a significant achievement that should deter similar misconduct.

No new laws

Apart from the landmark settlements, the legal legacy of the Gulf oil spill is more modest than previous spills that motivated Congress to enact new laws. The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill helped prompt passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, which transformed rivers and streams that were open sewers into fishable and swimmable waters. The Exxon Valdez spill in 1989 resulted in the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, which made it possible for companies like BP to pay civil penalties for oil spills in addition to criminal fines.

In response to the Deepwater Horizon spill, Congress passed the RESTORE Act in 2012, but this served only to ensure that civil penalties paid to the federal government by BP and its partners would be shared with Gulf coast states. The law was silent about drilling safety and future oil spills. Congress also did not act on recommendations made by the bipartisan commission that President Obama appointed to investigate the spill and offshore drilling, such as increasing energy companies’ liability limits for oil spills.

In terms of new regulations, the initial response was promising. The Obama administration imposed a brief moratorium on offshore drilling, reorganized the relevant offices within the Interior Department and enacted safety rules to prevent future oil spills. But the Trump administration has reversed many of these rules and pushed to expand offshore drilling, even though this policy is unpopular in many coastal states and faces significant legal obstacles.

The net result, 10 years after the Gulf oil spill, is that the U.S. still depends on companies like BP to conduct their activities safely, despite painful experience that doing so is risky. Today the oil industry is more committed to well containment efforts than it was in 2010, but there is no indication that a blowout today would be any less of a disaster.

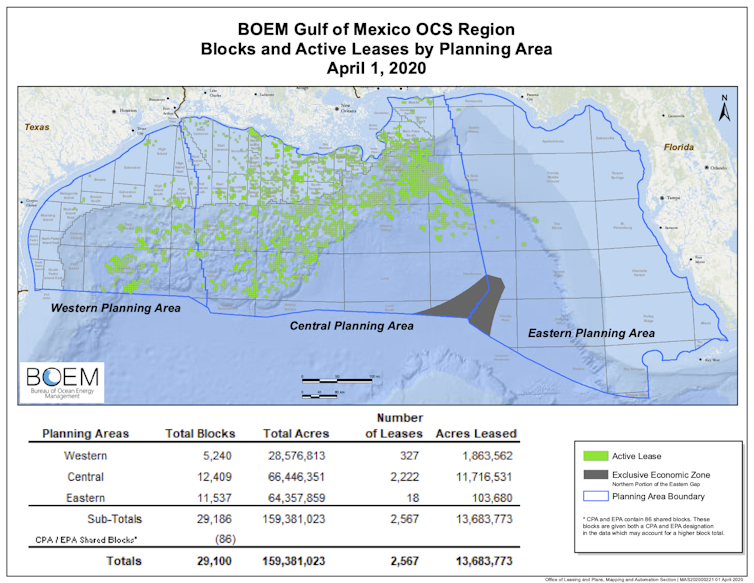

BOEM

The U.S. has not quenched its insatiable thirst for oil, even after the Gulf oil spill laid bare the risks of offshore drilling and evidence has mounted about the havoc of climate disruption. U.S. oil production set records through 2019 and may do so again once the nation emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic.

BP paid for its reckless conduct in the Gulf. The question that remains a decade later is when the U.S. will address its societal responsibility for the disaster.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

Credit: Source link