Illustration: Jeffrey Smith

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

After Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, Fox News — to the surprise of many, including founder Rupert Murdoch, who loathed Trump — became more successful than it had ever been in its already very profitable history. It had survived not only the loss of its longtime boss Roger Ailes, ousted the same year in a sexual-harassment scandal, but that of its former ratings leader Bill O’Reilly in another harassment scandal and that of Megyn Kelly, the anchor who the Murdochs had hoped might lead the network to a not-so-right-wing future.

Now President Trump was its star, a change so big that it demanded a reshuffling of the prime-time lineup. Sean Hannity, the former ratings laggard who had revived his career with an unquestioning devotion to Trump — and emerged as one of Trump’s inner-circle advisers — was given the 9 p.m. slot in a sop to MAGA world. But the biggest change was that Murdoch gave Tucker Carlson, a former magazine journalist who had served unremarkable tenures as a host at both CNN and MSNBC, an 8 p.m. anchor slot.

Murdoch made the unexpected move because he believed Carlson to be a moderate Republican who could be a counterweight — someone who could pull Fox away from reflexive Trumpism. The opposite happened: Carlson became a firebrand of the new Trump order and cable television’s ratings winner. The two men, Trump and Carlson, were suddenly the pillars of the post-Ailes network, and there was not much that even Murdoch could do about it.

The Breakup

Carlson’s success had become a bigger and bigger headache for Murdoch over the years. On the weekend of April 29, 2022, that headache scaled up dramatically as the New York Times rolled out a three-part series focused on Carlson and his role at Fox News.

Fittingly, the day part one was published, Carlson was fishing at the Rolling Rock Club in Ligonier Valley, Pennsylvania. Rolling Rock, founded by members of the Mellon family, those 19th-century industrial and banking aristocrats, with streams stocked with trout and a set of riding stables with all manner of elegant hunting accoutrements, in addition to the usual golf-and-tennis country-club amenities, is a stop on a particular 20th-century White Anglo-Saxon Protestant Establishment tour. How Tucker Carlson came to adopt and identify with this unreconstructed way of life, and with a passionate intensity unusual in places like the Rolling Rock Club, to transform its once-traditional conservative values into a down-market right-wing credo that played so big among Trump supporters on Fox News, was part of what the Times was trying to make sense of in its big story that weekend.

At Rolling Rock, Carlson declared to friends that he wasn’t reading any of it — although he tweeted a smiling picture of himself holding the Times’ front page dominated by his photo. But a three-part story in the Times, every barbed, surly, execratory, high-minded word of it, would be for anyone, no less a media and Washington insider, hard to ignore.

The Times’ series saw Carlson’s programming and ideological strategy as his deftly positioning himself as MAGA forward but at the same time distancing himself from Trump. But much more strategically, and marking his programming breakthrough, he was distancing himself from Fox and its overwhelmingly Irish Catholic right-wing barstool identity, as exemplified by O’Reilly and, now, Hannity.

“You know, I am not antisemitic, and I am not anti-Black; that’s a complete misunderstanding of what I am,” he would explain, this side of the edge of irony. “I am anti-Catholic.”

That was the retro message of the pale face, tousled hair, and prep-school uniform: Wasp. In this, his atavism was a purer kind than that of Fox or Trump. His reached back further, recalling an earlier America. The tumble into a diverse immigrant society began with the Catholics. Yes, take this fight back to the 1920s, when the sides were clear. The great modern mishmash in which anyone who occasionally visited a church was broadly subsumed into being a “Christian,” as though this was an uncomplicated designation, was very much, for Carlson, ewww thinking.

Even though Murdoch had himself been attacked in the starkest terms by the Times as outside of the bounds of political and journalistic acceptability — he had gotten his own series in 2007, and the Times had since embraced moral condemnation of Fox as a key element of its brand — this attack on Carlson brought Murdoch up short. For one thing, it not only proved Murdoch wrong but no-fool-like-an-old-fool wrong, the most pitiable kind of wrong. His view of Carlson as a country-club Republican, as a kind of well-mannered Protestant reclamation of conservatism — which Murdoch was able to maintain even in the face of Carlson’s Ukraine stances (he had spent weeks leading up to the invasion, nearly nonstop, excusing Vladimir Putin, if not praising him, if not outright siding with him) because Carlson was, in fact, a well-mannered Protestant and an attentive and charming dinner companion — had now been seriously challenged, if not dismantled, by the newspaper.

Where people still read the New York Times, they were appalled. And worse, Murdoch’s children — most of them, anyway — were among the people who still read the New York Times. So not only was he wrong, but his son James, who had taken a very liberal turn in recent years and had singled out Carlson as perhaps Fox’s most pernicious influence (and had likely been a helpful source for the Times’ story), was right. Even Jerry Hall, Rupert Murdoch’s fourth wife, whose views Murdoch was always eager to avoid, read the New York Times. She was now full of How could you let him on the air? How could you support this? … And what are you going to do about it? questions. But, pointing to another problem, Lachlan — his firstborn son, whom he had picked to be CEO of Fox Corp. after a decadeslong Succession-in-real-life struggle against James — did not read the New York Times. That incuriosity was just part of Lachlan’s disengagement from the media business and even Fox News itself. Murdoch was at a loss to defend his star, except to say, as though this were a virtue, that he didn’t really think, deep down, Carlson actually believed most of the things he said on the air.

So not for the first time, Murdoch was brought to the point of … what? Having to fire Carlson? He couldn’t do that even if he wanted to, and not just because of the millions of dollars of prime-time revenue that depended on him but because the New York Times wanted him to. But did he have to defend Carlson? That might make him seem like a Putin lover, which he most assuredly was not, and an anti-immigrant type, which was, for him, the worst kind of know-nothing conservative. Or did it mean he had to do something entirely different with Fox? But he could not imagine what that might be; as a television executive, which is what he had devolved into after having always seen himself first as a newspaper man, he really had no good ideas. Or would he just have to keep sitting there being lambasted by his children, his wife, their friends, and anybody he met in reasonably good company?

Carlson wasn’t Murdoch’s only headache. Two months later, in June 2022, the judge in Delaware’s Superior Court overseeing the $1.6 billion defamation lawsuit that Dominion Voting Systems had brought against Fox News ruled that the suit could also extend to Fox News’ parent company, Fox Corp. — and by extension its top executives, including Rupert and Lachlan. The first rule of libel law for a media company — beyond the actual law — is never to go before a jury. Ordinary people don’t like big media companies and are uneasy with the way the First Amendment seems to protect powerful organizations against little guys.

The second rule is to avoid discovery — the pretrial information gathering that would expose how the media sausage is made. Therefore, media companies in libel actions have two courses: move to dismiss — that is, ask the judge to decide early in the process that the media is within its constitutional rights and to throw out the case. Or, failing that, settle, no matter how expensive. Just a few months prior, Murdoch had figured the suit might cost him as much as $50 million. With the new ruling, that amount had potentially doubled or tripled … or much more. And yet his legal team, led by in-house counsel Viet Dinh, a DOJ official in the second Bush administration and a former Supreme Court clerk who also served as Lachlan’s de facto No. 2 at Fox Corp., seemed unconcerned.

Murdoch was in something like denial. One visitor to his Montana ranch found him absolutely unwilling to consider any view in which Fox could be at fault. Murdoch, the visitor discovered, was stuck in a place far from the real world. The Dominion suit had somehow become an attack on him and on his long career. He seemed angrily trapped in the company’s desperate and preposterous logic: that it was just airing the newsworthy opinions of important political figures.

“Why don’t you just settle?” asked the visitor. This provoked a Murdoch rant, lots of it hard to follow but leaving the visitor with the sense that Murdoch had found himself alone, up against all those who wanted him to settle, and that he, if no one else, was going to stand up for free speech. And at any rate, it wasn’t Fox’s fault. It was Donald Trump’s fault. He wasn’t going to pay for what Donald Trump did. Sue Donald Trump. The visitor came away wondering how this famously cold and analytic business mind had become such a hot mess.

Murdoch’s loneliness had seemed to fuse with his contempt for Trump. Trump had lost the election. But by refusing to concede and then mounting a campaign to convince his base — Fox’s base, and a base that would largely believe anything he said — that he had won, Trump had pushed the network into its untenable position. You see, Trump’s fault! As much as Trump could not leave the subject of his stolen presidency alone, Murdoch dwelled, his anger only increasing, on how Trump and his claims had damaged him and his business.

Around the same time, Carlson confronted the unconcerned Dinh, who told him not to worry, repeating what seemed to have become his go-to line: that they would take the case all the way to the Supreme Court if they had to, even though by then pretty much all the damage of the lawsuit — devastating discovery, humbling testimony, mountains of bad press, internal blame, a ten-figure award — would have been done.

In November, the widely predicted red wave failed to materialize in the midterm elections. At that time, its seemed particularly bad for Trump, many of whose chosen candidates were humiliated while a prime opponent and current Murdoch anti-Trump hope, Ron DeSantis, was elevated by a landslide result. With a new chapter seemingly opening on the American right, Lachlan Murdoch began telling people that Fox was going to focus on Dominion and get it resolved. But Rupert Murdoch wasn’t having it — he seemed to double down on a desire to punish Trump rather than resolve Dominion. Dominion wasn’t the problem — Trump was.

In terms of Trump, it seemed clear: In addition to being an “asshole,” “plainly nuts,” an “idiot,” a “fool” who “couldn’t give a shit,” who had “no plan,” who “just wants the money,” Trump was “a fucking crazy man” and a “loser.” The last was among Murdoch’s worst imprecations. Trump couldn’t win. Here were Murdoch’s true politics: There’s nothing to be gained from a loser. With Trump facing an incumbent president and a Democratic Party united against him, and with a marginalized message and his vast organizational disarray, not to mention certain looming indictments, the end was obvious: “Loser.” Without other alternatives, Murdoch had subbed in DeSantis. He was, in one of Murdoch’s good words, a “professional.” Unfortunately, that was exactly the sobriquet DeSantis was trying to avoid, as it might cause Fox viewers to flee. Indeed, everything Trump-like about DeSantis, everything he had so carefully worked at in order to seem Trump-like, Murdoch waved away. He wasn’t like that; that was all just because he had to; strategy stuff; he was a Florida Jeb Bush Republican.

At the same time, despite how the 92-year-old’s attention might wander, Murdoch retained an acuity for numbers. Whatever else was happening and for whatever reason, he seemed always to be up-to-date on the internal reports and focused on the faintest trends downward. Bad numbers were your fault. You had only one real job to do, and that was to bring good numbers. The underlying message was clear: He might despise Trump, but Fox must remain the dominant cable-news channel, holding and increasing its market share and continuing to generate enormous profits. But was there any other way to do this than giving the audience what it wanted, which was lot and lots of Donald Trump?

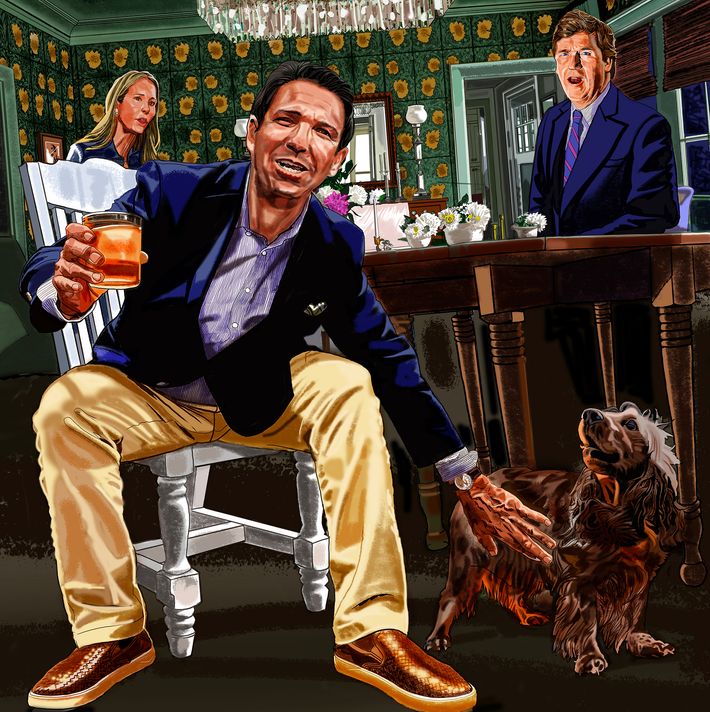

There had been quiet urgings at Fox for Carlson to be open-minded about Murdoch’s favored candidate. By early spring 2023, this had culminated in the DeSantises coming to lunch at the Carlsons’ home in Boca Grande, an exclusive community on Florida’s Gasparilla Island. And certainly, for DeSantis, this was a significant moment — an opportunity to reach out, to break bread, to make nice, to suck up to a plausible kingmaker. The DeSantis strategy, to the degree that he had one other than embodying the media dream of any alternative to Trump, was to make quick proof-of-product inroads into the MAGA base, for which he was heavily dependent on Fox. Winning Carlson over would be an important part of making good use of the network.

Carlson put DeSantis’s fate to a focus group of one: his wife. When they lived in Washington, Susie Carlson wouldn’t even see politicians. Carlson himself may have known everyone, dirtied himself for a paycheck, but not his wife. In her heart, it was 1985 and still a Wasp world, absent people, in Susie Carlson’s description and worldview, who were “impolite, hyperambitious, fraudulent.” She had no idea what was happening in the news and no interest in it. Her world was her children, her dogs, and the books she was reading. So the DeSantises were put to the Susie Carlson test.

They failed it miserably. They had a total inability to read the room — one with a genteel, stay-at-home woman, here in her own house. For two hours, Ron DeSantis sat at her table talking in an outdoor voice indoors, failing to observe any basics of conversational ritual or propriety, reeling off an unself-conscious list of his programs and initiatives and political accomplishments. Impersonal, cold, uninterested in anything outside of himself. The Carlsons are dog people with four spaniels, the progeny of other spaniels they have had before, who sleep in their bed. DeSantis pushed the dog under the table. Had he kicked the dog? Susie Carlson’s judgment was clear: She did not ever want to be anywhere near anybody like that ever again. Her husband agreed. DeSantis, in Carlson’s view, was a “fascist.” Forget Ron DeSantis.

But the question of whom he could fully support as a conservative candidate for president was a more complicated one — and had started to feel personal. Carlson regarded himself as being in a small circle of clear-eyed people who knew Trump well and knew exactly who and what he was. If the field was Trump, DeSantis, and various hopeful brand builders and gadflies, then Carlson, the second-most-famous person on the right — with that new political X factor, a television persona — might realistically become a true MAGA-friendly Trump alternative himself. Once you saw it, the logic was undeniable.

Carlson had risen on the Fox-Trump juggernaut, but that, he was concluding, was a spent force — and a broken partnership. He had spent ten hours in his Dominion deposition. The Murdochs and their executives had dumped their problem on him. You don’t want to work for people who you think might hurt you. He had become what Fox demanded, and now he could be, he feared, left out here on his own.

He was also aware that voices in the Murdoch family were relentlessly campaigning to have him fired — and that there was a not-small chance he would be. If that came to pass, Carlson’s transformative, cometlike success would abruptly, and ignominiously, end. That had always been part of the strange alchemy of Fox News. It made you — gave you a singular name: Tucker, Hannity, O’Reilly, Megyn — but somehow did not give you a star’s independent life. Megyn Kelly, Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck, Greta Van Susteren, Paula Zahn, Fox superstars, had tried to go somewhere else and quickly faded away. It was a fate that weighed heavily on Carlson.

His only alternative … might be to run for president. The White House. There it was, absent a note of irony: He could be unemployable but for the presidency. (Sometimes it also seemed that he regarded running for president as a further part of his inevitable martyrdom — as well as a convenient way to get out of his contract.) But if he did run, he knew what he would run on — he had been thinking about that. He would run on foreign policy. A year into the bog of Ukraine, his views had only hardened: The foreign-policy Establishment, followed mindlessly by the entire political Establishment, was risking everything — a functional world order, economic stability, as well as Armageddon — in a conflict that would only result, without the active involvement of NATO troops, in Ukraine’s capitulation. Be realistic! Here is what gripped him: not just that Volodymyr Zelenskyy was a fake and Putin, you better believe, real, but that liberals, and he would include here the Republican center as effective liberals, weren’t even really talking about Ukraine — supporting Ukraine was just some accepted aspect of good manners and public virtue. Well, fuck that — here was a reason to run. He had a message. He was the antiwar candidate.

Murdoch, presented with rumors about Carlson’s possible interest in the presidency, blamed this on Lachlan, holding his son responsible for not controlling the ratings winner at the network — who, of course, precisely because of his ratings, could not be controlled. Murdoch told friends with disbelief that Lachlan wanted Carlson to become president: “My son wants his own president.” It seemed intolerable to Murdoch that he might be responsible for another president representing conspiracies and populist emotion — that is, representing Fox. And so he dismissed it (with almost the same words he had once used to dismiss Trump’s prospective candidacy): “Won’t happen.”

Illustration: Jeffrey Smith

The week before the Dominion trial was set to begin, a nervous Carlson spoke to Dinh. Carlson was trying to get a better sense of strategy and confidence levels. Dinh, who Carlson thought had perhaps been drinking, told Carlson he was reconciled to being the fall guy. “That’s okay with me,” he said stoically, but eyeing, Carlson understood, a rich payout from the company, if worst came to worst. (Indeed, in August, Dinh departed Fox with a $23 million golden parachute.)

On Monday, April 17, the day the jury was supposed to be seated and opening statements begun — before a day’s delay was declared — Murdoch told Carlson Dominion was holding to a demand of a billion dollars in damages. For Murdoch, this was a nonstarter: He would not endure the humiliation and defeat of paying a ten-figure settlement in the case. It would be not only a record-shattering sum but also tremendous fodder for his enemies (like the Times) when it came to writing headlines.

The positions were: Fox’s — or Murdoch’s — continued determination not to go to a billion but with anything under it fair game, and Dominion’s expectation that it had considerable room to go above $500 million with the hope that it could yet break through Fox’s billion-dollar resolve.

There was also a sweetener: putting Hannity on the table. The Fox News host would be fired concurrently with the settlement. Murdoch had always wanted to get rid of Hannity, and perhaps MAGA insider Hannity’s scalp would make Dominion more likely to accept a nine-figure settlement? It was a thing they might have done without this suit, and might do in the future anyway. Still, rolling it into the deal was convenient psychologically and tactically.

But it would be a gentleman’s agreement. There would be no official side letter about firing Hannity, no real acknowledgment even in the settlement that they were doing this as part of the deal. In one sense, there would be no enforcement mechanism. But, practically speaking, after a settlement is reached, the parties have a period of time, often up to a week, to file with the court. Technically, a settlement could come apart in that time if anticipated conditions or actions — for example, a gentleman’s agreement — were not honored. So Fox would make its gesture, this coincident event, within a week.

But Dinh’s offer of Hannity’s scalp as a sign of future reform at Fox News — meant to inspire trust in that reform — at $500 million was soft enough to keep the number moving upward. At some point on Monday, with the trial again set to kick off the next morning, the logical midpoint between $500 million and a billion started to come into view. Dominion understood that it would be able to better its position by hundreds of millions of dollars while still falling under Murdoch’s B-word line in the sand. How to nail it?

Murdoch’s annoyance with Carlson, especially over Ukraine, was balanced by how much Murdoch enjoyed Carlson’s company, looked forward to speaking to him on the phone, and appreciated the fact that he had built a good relationship with Lachlan. Murdoch even liked Carlson on the air, except for when he was spouting his obvious bullshit. But even that he did well. He didn’t think Carlson was actually a racist, although he thought he could really be an asshole. More and more, though, he was bothered by the reports that Carlson might run for president. It seemed ludicrous — like Trump running for president. It just lacked respect for politics itself — the thing Murdoch most respected. He was pissed at Lachlan for not reining Carlson in.

Shortly before the Dominion case was set to go to trial, Murdoch — to Carlson’s pleasant surprise — invited the host to join him and his new fiancée for dinner at his Bel Air mansion. Carlson liked Murdoch, or, at least, found him to be a character of great fascination. He might be a savage animal, but he also had great manners: You were well received in his company, and he seemed to like to hear what you had to say (not many billionaires actually listened to you). The new fiancée, Ann Lesley Smith, was very different from Jerry Hall, from whom Murdoch had recently split. Smith was a 66-year-old die-hard conservative who seemed to idolize Carlson and, Carlson reported to friends, referred to him as a “prophet from God” during the evening. This might be nuts, thought Carlson, but on the other hand, the couple seemed very much in love, and it was a happy evening. Murdoch called Carlson afterward to thank him for an enjoyable meal — though he ended the short-lived engagement with Smith just a few days later.

The dinner reinforced for Murdoch that he really did like Tucker. He liked him much better than he liked Hannity, whom he didn’t like at all. But there was, too, a sense that the problems he created were greater than his value. Among his children, the Fox backlash could often seem to be Tucker backlash. Without him, you might take down the Fox temperature by what? Twenty percent? Thirty percent? Maybe more? This was a Murdoch calculation: How much could you cool things and still have Fox be Fox?

Hannity had been offered as a sweetener. But Carlson, the ratings leader, increasingly the real, hard-core face of the new demagogic right wing, was sweeter. He won’t go to a billion. He just won’t. Not going to happen. It’s Rupert. You know Rupert and money, when he digs in. So that’s it. We’re here.

Seven hundred and eighty-seven million dollars. There it is. Far and away the largest defamation award ever made, outside of Alex Jones — and Jones isn’t good for it and we are. And while we’re not making this a part of anything — he can’t live with that — we do understand what you want and things will happen. It will happen by the end of the week. It will be done.

Can you live with that? Can you live with $787 million … and Carlson?

On Tuesday, April 18, Fox had a plane waiting on the tarmac at the private-use airport not far from Boca Grande ready to take Carlson to Delaware for his testimony at trial, which might begin as early as Wednesday morning. Slightly before 4 p.m., he was notified that a settlement with Dominion had been reached. He would not have to get on the plane. It was over. Carlson went on the air the rest of that week but never mentioned the lawsuit or giant settlement that his employer had agreed to pay out.

The general with-us-or-against-us protocols at Fox News have reliably meant that a notable defenestration — and there have been many — is preceded by a series of leaks and reports so that when the firing comes it isn’t entirely a head-spinning surprise for the audience. Fox’s PR arm, led by Ailes protégée Irena Briganti, had a playbook for besmirching anyone soon to leave the network (by choice or otherwise).

But in this instance, there was no prelude. Briganti and her people did not learn what was about to happen until 5 a.m. on Monday, April 24, six days after the settlement. At 11 a.m., just as Carlson had begun work on that evening’s show, Fox News CEO Suzanne Scott called him. After some idle chat, Scott said, “Listen, I think we have to go our separate ways.”

“Go where?” said a baffled Carlson.

“No, we’re taking you off the air.”

“Why?” asked Carlson, so perplexed that he remained unruffled. “For how long?”

“No, we’re taking you off the air permanently.”

“Are you firing me?”

“No, but we’re taking you off the air.”

Now concerned, Carlson said, “Have there been accusations against me?” There was a recently filed suit by a former Fox booker accusing Fox and the Carlson show of sexism and harassment — but the booker acknowledged that she had never personally met Carlson. “Are you saying that I violated my contract?”

“We’re not going to get into specifics at this point. But we would like the statement to acknowledge that our parting is by mutual agreement.”

“You would first have to tell me what I’m agreeing to.”

“We’re just agreeing that you won’t be on the air. Can you agree to that?”

“Suzanne, why don’t we step back a moment and actually see what we can reasonably agree to. We obviously don’t want a war.”

“We definitely don’t want a war. But we’re announcing this right away.”

“When?”

“Immediately. So if we can’t agree, then we should end the call.”

“All right.”

The announcement followed less than a minute later with no suggestion at all as to why the network’s top-rated star had been abruptly taken off the air — not to the public at large or to Carlson, his lawyers, or anyone inside Fox. Carlson’s company email was cut off, and the security guard provided by the network began to pack up his things. As a measure of how much Carlson had become a political phenomenon in the nation — and with no reasonable explanation forthcoming — for nearly two weeks his abrupt removal consistently ranked among the top stories in U.S. media, as large or larger than any other political, social, business, or international news.

A few days later, while the Carlson household was getting ready for its summer move to Maine, Murdoch called to thank Carlson for his 14 years at the network and his contribution to all the success they had had together. “I just hope you know I’d like to stay friends,” said Murdoch. “I hope we can.”

Carlson was already working on something new. Four hours after he was sacked, Elon Musk had called.

During the period shortly before and after Carlson’s de facto firing, Trump, who had run his political campaigns as well as his White House largely through Fox News, was finalizing his move to CNN. Fox News began as a play to take market share from CNN, then the singular cable-news giant. It not only succeeded in its ratings war with CNN but broke the cable-news market — and, practically speaking, the culture at large — into a monolithic conservative audience and everyone else.

Murdoch had never liked Trump, but his hatred had continued to deepen for many reasons: Trump’s unbreakable hold on Fox News during his White House years; the near billion dollars that the colossal nonsense about election fraud and Fox’s co-dependent abetting of it had now cost Murdoch (with the possibility of another billion or more in further lawsuits); and the grim prospect of this new campaign and a horrifying restoration. After 70 years of media dominance, an agitated Murdoch had spent as much energy as he could muster trying to break Trump and, as much as might be possible, to patch up his own legacy — even as he refused to acknowledge that it needed to be patched up. In another contradiction he could not acknowledge, he expected everyone to maintain Fox’s ratings even as Trump was, at Murdoch’s urging, increasingly frozen out of the network’s coverage.

More than the uncharted legal perils Trump faced, Murdoch’s efforts to keep the former president off the air seemed to be the real crisis of Trump’s early-phase campaign — to be deplatformed from the primary channel to his core supporters. But this then prompted an existential question for both Fox and Trump: Who was bigger? The Fox monopoly backed by the will (and money) of the most powerful man in the history of media or the former president and television personality who had become the most famous man on the planet? So Trump had placed a call to CNN.

Trump, the simple machine, makes the obvious and characteristic countermove. Fox controlled its world, and conservative politics needed to work within it — that was Ailes’s ecosystem and the power of monopoly. But Trump, with his abiding belief that true fame is bigger than anything, was untroubled by that. So, yes, he understood that of course CNN would be willing to put aside its years of casting him as democracy’s Golgotha and a common criminal, as well as Trump’s constant efforts to mock and demean CNN, to improve its own fortunes. (CNN would justify this as strictly a news choice — but what’s newsworthy and what’s profitable are, ideally, overlapping.)

The Trump town hall on May 11, less than three weeks after Carlson’s firing — with a Fox audience in essence bused in to CNN — had originally been set for 9 p.m. to avoid competing with Carlson’s high ratings. Trump would go against Fox but, in a subtle yet important point about the growing individual powers at Fox, not against Carlson, who was still in his place at the network when the CNN arrangements were first made. No, he’d challenge Hannity. This provoked great agitation in the Hannity camp and remonstrating with Fox News CEO Scott: This is what’s going to happen, you see, you see! We’re up against Trump. Then, after Carlson was taken off the air, CNN was told by the Trump camp that it had to move the town hall to eight. It had little choice but to oblige. Without the higher-rated Carlson to cater to, Trump could now extend a courtesy to Hannity, reminding him whose favor he most depended on. Hannity begged Trump not to let the CNN town hall run over into his hour — when, in fact, he had an interview scheduled with Mike Pence. (“You see,” said a Trump inner-circle staffer with happy sarcasm, “you can’t say all those years of fellating POTUS on air didn’t pay off for Sean.”)

In a single move, Trump showed that he owned Fox’s remaining star and gave Murdoch a demonstration of what 18 months of the Trump campaign’s guerrilla attacks on its programming schedule might look like. Fox would simply become another Republican outlier for Trump to run against. Not incidentally, the Trump weight broke CNN just as it was threatening to challenge Fox: The town hall was a direct cause of the firing of CNN chief Chris Licht a few weeks later.

In the days after the CNN Trump town hall, Murdoch told friends, in a new ironic tumble of virtue, that he would never have allowed Trump — whose performance at the CNN town hall was quite a singular encapsulation of his many years of Fox-enabled gaslighting and shamelessness — to do that on his watch. Meanwhile, the Trump campaign was in discussions with every network (including Fox) for prime-time appearances.

Within the space of a few weeks, Fox lost both an exclusive Tucker Carlson and a virtually exclusive Donald Trump, its two ratings pillars. In a taped interview with Bret Baier in early summer, Trump jauntily attacked Murdoch, remarks cut from the show.

The official line from Fox, internally, to advertisers, media, and the industry, was that it had lost big stars before and, beyond the short term, had suffered very little.

It was protected by its monopoly.

That monopoly system, with its blunt-force strength and unforgiving enforcement arm, went to work in the days after Carlson’s ouster. Briganti set up a war room tasked with pushing out the multi-layered case for getting rid of him: in sum, general perfidy, moral turpitude, and bizarre views. Not having had any warning of the move against Carlson and the time to build a slow-burn case that might make his end seem inevitable, nor an actual reason for why he was taken off the air, Briganti piled it on in particular shocked-shocked fashion. It was also personal for Briganti. Fox — that is, Briganti — released to its corporate sister publication, The Wall Street Journal, snippets of Carlson’s damaging emails, including the fact that he had called a senior woman executive at Fox a “cunt,” implying that this was Scott, the network’s seniormost and nearly singular female executive, when in fact it was Briganti herself, which fact Briganti conveniently elided. The network offered background briefings suggesting that more misconduct by Carlson would soon be revealed.

Not long after he was taken off the air, Carlson wrote a letter to Rupert and Lachlan Murdoch, Dinh, and Scott calling the allegations of sexual misconduct being “shopped by Fox” to media outlets “a lie, as you well know.” He suggested an amicable ending to the relationship with a note of threat: “I’d ask that you put a stop to this immediately before it escalates in a way that hurts everyone very badly.” Murdoch assured Carlson that no such efforts were underway or would be tolerated.

One ironic aspect of Briganti’s campaigns — not limited to Carlson — is that they so often take place through the New York Times. That is, the Times’ animosity toward Fox made it the oddly perfect vehicle through which Fox might damage its own people. Briganti’s voice had been trackable to an attuned reader through the Times’ three-part critique of Carlson a year before his removal; it would be evident in the Times’ account of Fox’s poor handling of the Dominion legal strategy with the blame placed here on Viet Dinh (quite an indication either that the Murdochs were imminently planning to get rid of him or that Briganti herself was taking him on — or both).

Fox’s case against Carlson, retailed through the liberal media in the weeks after he was taken off the air — while Fox ritually denied there was a leaker or even that there was a case against him — was a case against itself. Fox might be white, chauvinist, nativist, and conspiratorial in its views, but Carlson, in his six years in prime time, had become more Fox than Fox — that was effectively the company’s case against him.

Unable to admit that Carlson was a casualty of the Dominion settlement — and this had become such an unwritten secret at the highest echelons of Fox that the secret seemed no longer to exist, with Murdoch waving off the settlement as Dinh’s — Fox had landed on a rationale that basically accepted the liberal case against itself. Carlson had to go because … he offended the New York Times!

The company’s case against Carlson was being made almost entirely for people who did not watch Fox News. When the Times had gone after Carlson in its three-part series, it had had no effect on his ratings — his audience stayed in place, unaffected and perhaps largely unaware of the newspaper’s furious critique. Now, as the ratings came in after he was pulled off the air, roughly half of Carlson’s audience failed to show up, uninterested apparently in what Fox might offer in his stead.

After a week of disastrous ratings in the 8 p.m. hour and spreading across the evening, Murdoch began to actively panic, blaming Scott and blaming his son for not having better programming suggestions and reviving the idea of Piers Morgan in the slot. Murdoch also proposed putting in Carlson’s place a roundtable of Wall Street Journal editorial writers — “wise men,” in Murdoch’s programming concept. A month later, MSNBC, the historic last-place news channel, was beating Fox in key time slots.

The case Briganti was making against Carlson was one for “cause” — that is, one under which Fox could cancel its contract with Carlson and walk away from its obligations. But, contradicting the public case, Fox wasn’t firing him. In fact, it was adamantly refusing to sever his formal employment. As Carlson’s lawyer, in the weeks afterward, pressed more and more for a resolution that would allow Carlson to return to broadcasting in time for the election season — even offering to forgo the payout on the two years left on his contract — Murdoch himself, as the time-slot numbers plummeted, became more and more insistent on keeping Carlson from competing with the network. “We might not get the audience, but no one else will,” Murdoch said, appearing to arrive at some point of satisfaction and casting 2 million or so right-wingers into a political and media void.

Still, by the summer, as Carlson seemed intent on baiting Fox into suing him with a regular schedule of broadcasts on Musk’s X (formerly Twitter), Fox seemed reluctant to press beyond threatening letters. Will Carlson’s shtick work in a different medium — social-media monologues? That is likely not the right question. Rather, how many new shticks will Fox be facing? How many new voices will Trump, that ultimate shtickmeister, profitably inspire to the far-wacko right of Fox?

Two months after Carlson was taken off the air, Fox finally rejigged its schedule, demoting Laura Ingraham to the 7 p.m. hour, leaving Hannity in place, and filling out prime time with Jesse Watters and Greg Gutfeld, both more insult conservatives than ideological ones. (“Do you think they’re funny?” an unconvinced Murdoch was asking people.)

Carlson and Trump were talking together about how they might team up in a series of counterprogramming events and go head-to-head against Fox. (And they did so on August 23, putting up an interview on X at the same time Fox News began airing the first Republican primary debate — without Trump, of course.) Trump also began to casually discuss Carlson as a possible vice-president, a wicked -maneuver against Fox and Murdoch. Trump’s political wars were always as much against Republicans as against Democrats. It was natural to now take the fight to Fox.

Like all monopolies (and religions and single-party states), Fox was built on a great, uncompromising, stubborn, black-and-white literal-mindedness: us against them. Appropriately, it has been felled not just by its own overreaching and sense of impunity but by something like a conflicted conscience: The Murdochs feel bad, about Carlson, about Trump, about themselves. Too late, they are trying to reject the monsters they have created.

But the monsters, Trump and Carlson, are by this time bigger than the network that made them. In that age-old media tension, the best talent becomes larger than the platform by which it has been nurtured — and walks out the front door. Elvis leaves the building.

In the bittersweet department, accompanied by the wild laughter of his enemies, you have the lonely figure of Rupert Murdoch, 92-year-old Rupert Murdoch, now shaded by doubt, ambivalence, regret, bafflement, and the harsh and clanging voices of his children. Not the best mind-set with which to hold a kingdom.

Excerpted from The Fall: The End of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty, by Michael Wolff (Henry Holt and Co.; September 26, 2023).

Credit: Source link