You know the drill – walking through the city alone you have your headphones on, your music playing; it guides your footsteps, marks your rhythm. You see cars and trucks, ongoing construction work, but hear only what you want to hear. But what if we built a new relationship with urban noise, rather than escaping from and denigrating it?

After travelling through the bush and absorbing its quiet ambiences, returning to the cacophonies of the sonic city can be exhilarating. The body is immediately swamped with an energy that speaks of action, progress, and possibility.

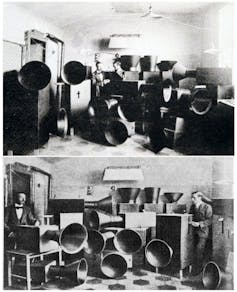

Wikimedia Commons

Countless working machines and human activities combine to form an intoxicating urban roar. And yet, in just a few days, our bodies are fatigued by the constant bombardment of noise. Our response is to withdraw. The internalising of thoughts as the outer world presses in; our voice silenced by the city’s indefatigable roar.

The former characterisation – that of the exhilarating city – can be traced to the Futurists, an amalgam of 1920s Italian fascists who sensed great excitement in the march of modernity. Their sonic champion Luigi Russolo invented grand machines called intonarumori that could recreate the sounds of modernity in concert hall conditions.

In his manifesto The Art of Noise (1913) he writes of the sonic city:

our ears rejoice in it, for they are attuned to modern life, rich in all sorts of noises.

Noise-sounds, as he called them, were to be celebrated.

In contrast, acoustic ecology, a sonic outgrowth of an emerging environmental sensibility, some 50 years later came to bemoan the urban soundscape as a mess of sounds that prevented us from forming enriched listening relationships with the world.

Tri Nguyen

This awareness was facilitated by the electrical revolution, and the rise of the motorcar, in which the now familiar drones of the city were becoming dominant. The movement’s founder, Murray Schafer wrote in his book The Tuning of the World (1977):

when […] the voice cannot be heard the environment is harmful.

His suggestion being that, when individual voices are silenced by the roaring city, we have lost our shared aural culture.

Together these divergent views form an opposition that provides sound makers – musicians, sound artists, composers and sound designers – with endless conversational fodder.

Noise music aficionados can take great offence to the charge that silence is pure, while trained composers may dismiss noise music as an undifferentiated cacophony. This musical clash is surely a matter of taste.

Take for example the band Einstürzende Neubauten, whose noise music seems to grow increasingly refined. At a recent Melbourne concert their arrangement of “junk-like” material appeared, and sounded, like a post-apocalyptic ensemble of profound poetic grace.

The distinction becomes even more interesting when considered in the context of sound culture. Sonic theorist Brandon La Belle suggests in his book, Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art (2006), that acoustic ecologists, by dismissing urban noise, might be missing the world’s most expressive moment.

Elsewhere he brings attention to the unerring silences of city-suburbs, where the absence of noise is associated with a form of social control. In contrast to the silenced suburbs, Franciso Lopez’s La Selva (1998) reminds us that the natural world is anything but silent – his rainforest composition blares with multiple noises.

So in fact the silence-noise distinction is a constructed difference rather than a reality. Yes, the city can be noisy, but equally its internal spaces and suburban stretches can be oppressively silent. And the bush constantly reminds us that it is a mixture of the two – think of the silence of a still atmosphere before the onslaught of a storm.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NwrrTAX07TI

Urban noise becomes problematic when it is constantly present. Where there is a constant, there is relentless similarity. And where there is relentless similarity, there is boredom, routine and banality.

The reason a city’s roar can arouse excitement in us after a time of absence is because, for a moment, it acts as a point of difference. A sonic flood momentarily overwhelms the body, which must adapt to the new environment.

But upon adaption, bodily stresses caused by noises become the norm. And like all living things, when stressed, we become reactive.

Have we silenced our suburbs to act as a stark contrast to the city’s busy centres?

Do we withdraw into our iPads, smartphones, and noise-cancelling headphones to escape the city’s noises? It seems our bodies are reacting to stress.

I concur that acoustic design is a matter of retrieving our aural culture, that listening is an integral part of connecting with each other and the world around us. But noise removal is not the only answer.

Urban planners might begin to design a diverse city by supporting a creative reshaping of the sonic city. Sound installation artists have shown us multiple ways that we might begin to achieve this.

Bruce Odland and Sam Auinger’s Harmonic Bridge (1998), Susan Philipsz Lowlands (2010) and Max Neuhaus Times Square (1977-) are just three examples of constructed sonic localisations that reshape urban noise into evocative listening experiences.

We should build new relationships with urban noise, rather than escaping from and denigrating it. To do this we must become urban storytellers and actively reshape the urban roar, rather than becoming its passive and defeated receptors.

Credit: Source link