In a cross-sectional study published in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition, researchers from China investigated the potential association between muscle mass and the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) among adults in the United States of America. They found UPF intake to be linearly correlated to the risk of low muscle mass among adults, highlighting UPF intake as a potential risk factor for sarcopenia.

Study: Higher ultra processed foods intake is associated with low muscle mass in young to middle-aged adults: a cross-sectional NHANES study

Background

UPFs are industrially manufactured food products containing high levels of sugar, salt, additives, and unhealthy fats. As the name suggests, they undergo several rounds of processing to enhance taste, shelf life, and convenience, leading to their easy availability and increased popularity in recent years. UPFs often lack the nutritional quality of whole foods and have been linked to obesity, type-2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Consequently, public health organizations advocate reducing UPF intake to promote better health outcomes.

Sarcopenia, a condition associated with aging, involves a gradual decline in muscle mass and strength. While resistance training is a key strategy to combat sarcopenia, dietary choices also play a significant role. Low muscle mass is known to be a determinant of health outcomes and mortality risk. Evidence suggests that several factors influence low muscle mass, including breastfeeding history, genetics, birth weight, physical activity levels, socio-economic status, history of diseases, and nutrition.

Excessive consumption of UPFs has raised concerns about muscle health due to increased food additives intake, nutritional deficiencies, and potential effects of UPFs on gut microbiota. Therefore, researchers in the present study aimed to examine the relationship between UPF consumption and muscle mass in adults to provide insights into preventive strategies against sarcopenia.

About the study

The present cross-sectional study analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Participants aged 20-59 from the 2011-2018 cycles were included. The application of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in a sample size of 10,255 individuals.

Dietary data were collected through 24-hour dietary recalls taken in person. UPFs from the Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) were identified using the NOVA classification system. The UPF intake (as a proportion of total daily energy/grams intake) was estimated in terms of %kcal and %gram.

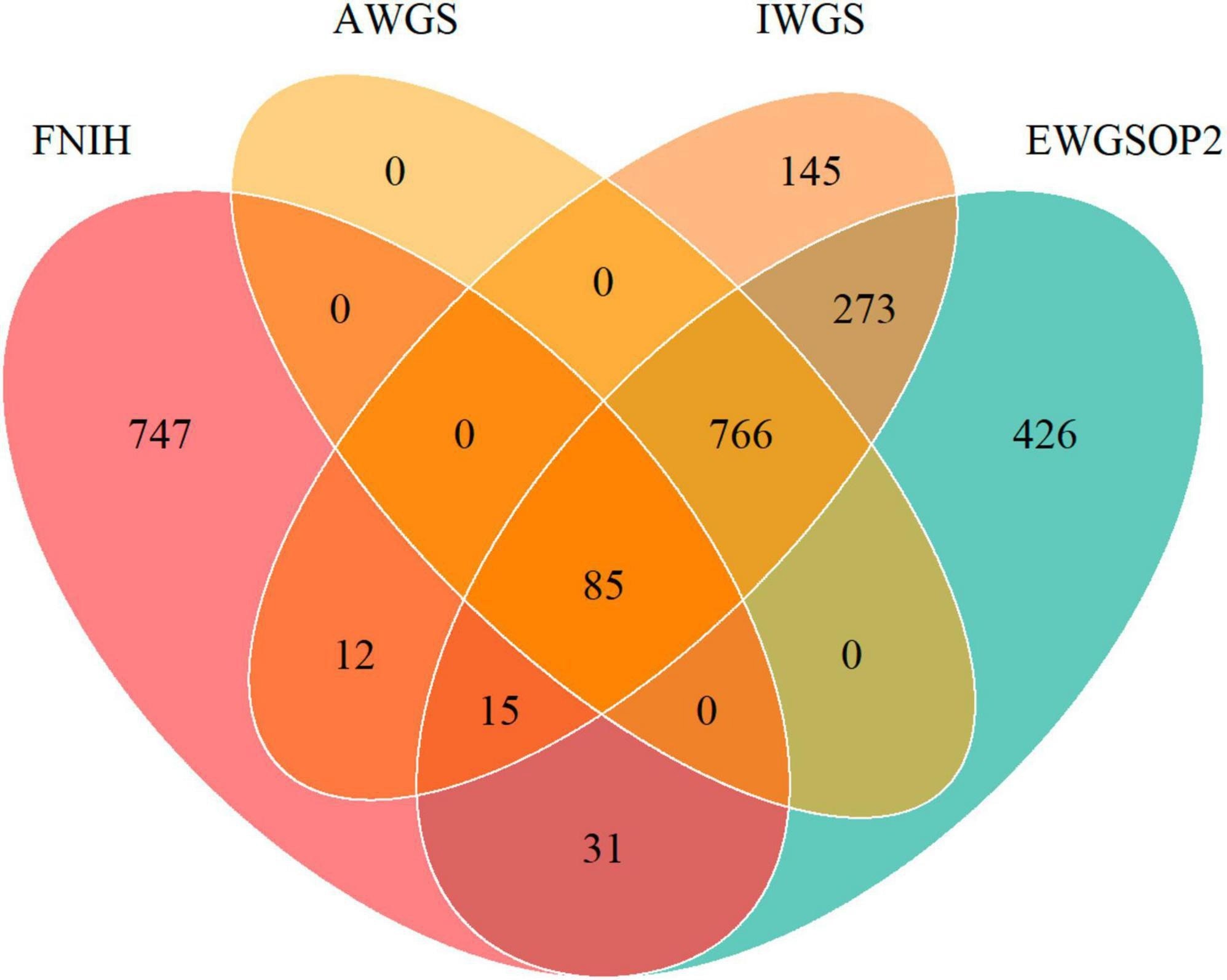

Height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were measured for each participant. Appendicular lean mass (ALM), a proxy for skeletal muscle mass, was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The primary outcome was low muscle mass, defined as ALM/BMI < 0.512 for females and < 0.789 for males. Sensitivity analysis considered updated definitions from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2), the Asian Working Group on Sarcopenia (AWGS2), and the International Working Group on Sarcopenia (IWGS).

Various socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors (such as alcohol consumption, smoking status, and physical activity), chronic diseases, and urinary biomarkers were adjusted for in multivariate models. Statistical analysis involved the use of Taylor series linearization, Student’s t-test, weighted percentages and means, survey-weighted chi-squared tests, logistic regression, odds ratios, and sensitivity analyses.

Venn diagram showing the overlap of prevalence of low muscle mass by different definitions of FNIH, EWGSOP2, AWGS, and IWGS.

Venn diagram showing the overlap of prevalence of low muscle mass by different definitions of FNIH, EWGSOP2, AWGS, and IWGS.

Results and discussion

The weighted prevalence of low muscle mass was calculated to be 7.65%. Similar percentages of UPFs calorie intake were observed in individuals with normal and low muscle mass (55.70% vs. 54.62%). Those with low muscle mass tended to be older, male, with lower income, lower education levels, and lower alcohol consumption. They also showed a higher prevalence of various health conditions, lower total energy and protein intake, and a reduced eGFR (short for estimated glomerular filtration rate). Significant linear associations were found between UPFs consumption and low muscle mass (P overall = 0.0117). After adjusting for confounding factors, participants with the highest UPFs intake showed a 60% increased risk of low muscle mass and decreased ALM/BMI. Sensitivity analysis supported these findings, except for the IWGS definition, where the association between high UPF intake and low muscle mass was not statistically significant.

The novel study is strengthened by its large sample size, thorough assessment of UPF consumption, the use of DXA for muscle mass measurement, and consideration of multiple sarcopenia diagnosis definitions. However, the study is limited by its lack of causal inferences, potential recall bias in dietary data collection, potential misclassification of UPFs, and the simplistic classification of physical activity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study highlights a clear link between UPF consumption and muscle mass. The potential adverse impact of UPFs on muscle mass revealed in these findings emphasizes the importance of dietary interventions for promoting muscle health. Limiting UPF intake could be an effective strategy for potentially preventing low muscle mass in adults, leading to improved physical function later in life.

Credit: Source link