It was an almost Churchillian phrase, had the man who pronounced it not been so wary of his own media-consciousness: “This is not a day for soundbites, but I feel the hand of history is on our shoulders.”

Tony Blair was about to sign an agreement, with Irish taoiseach Bertie Ahern, on behalf of two neighbouring sovereign states, with the backing of paramilitary groups and of populations that had been at each other’s throats on and off for 70 years at the cost of thousands of lives on each side.

That agreement was signed on Good Friday, 10 April 1998.

The date was not quite an auspicious coincidence; it had been laid down by American Senator George Mitchell who, as US President Bill Clinton’s special envoy, had been a facilitator trusted by both sides. In part this was for its symbolism, but it also meant he could be home with his family by Easter Day.

Those who signed up called it the Good Friday Agreement; those forced reluctantly to accept its terms still call it merely the Belfast Agreement. Its terms have come to be a guarantor of peace – or as near to it as Northern Ireland ever comes – for 20 years. Now is a curious time to threaten it.

Yet the lessons of history are repeatedly forgotten, or disregarded by those who find them inconvenient for their present circumstances. In Blair’s more recent words, it is an “irresponsibility that is frankly sickening” that there are British politicians who would “sacrifice peace in Northern Ireland on the altar of Brexit”.

His views are shared by his predecessor, the Conservative Prime Minister John Major, who engaged with and edged along the politically precarious process of engagement with the IRA. But opposition from his own party’s right wing meant only a Labour prime minister could carry it through to fruition.

April 2018, with an uncertain Brexit hovering over the graveyards, is an apposite moment to recall the grim origins of the ‘peace process’, which lie in part in a particularly gory incident on the streets of Belfast that brought home to the British public the horror that most have since preferred to forget.

It was shortly after noon on Friday 19 March 1988, two weeks before Good Friday. Father Alec Reid, a Catholic priest, was walking down Andersonstown Road when he heard angry shouts and animal-like screams mounting in murderous crescendo.

Two British army corporals had apparently accidentally driven into the path of the funeral procession of an IRA member, himself killed by a loyalist gunman at a funeral three days earlier. Fearing a repeat attack, the crowd set upon the two soldiers, who were wearing civilian clothes, in their car. One of the soldiers drew his service pistol and fired in the air. They were dragged from the car.

The men were overpowered, beaten and stripped. They were then shot dead on a patch of wasteland next to Andersonstown social club.

Footage of the incident shocked the world. But with it came an image of compassion: a Catholic priest, grief etched on his face, ministering to one of the British soldiers in death. Few who looked upon that scene were aware that a regular visitor to Reid’s confessional was a former barman named Gerry Adams.

Indeed, Reid was already by this time acting as a go-between for Adams, the leader of the IRA, and John Hume, head of the moderate nationalist SDLP. The incident on the Andersonstown Road strengthened his determination to bring about an alliance between the two men. Staggeringly, it emerged years later that he was carrying a message from Adams to Hume on the day of the killings.

The IRA were understandably toxic to British politicians. The aim was to bring them in from the cold. Hume was a republican but respectable. The theory was that he might be able to convey to London what it would take to make the IRA call off their campaign of violence.

The most difficult issue was the IRA’s total refusal to recognise an inner-Ireland border guarded by soldiers and armed police. (Sound familiar?)

I understood all this. I had grown up in Northern Ireland; had lost two schoolfriends to the IRA. I was also aware of what had led to the violence: my Protestant grandfather had been a landlord who had three votes in local elections, while his Catholic tenants had none.

Talking to Adams represented a political risk for Hume. Reid orchestrated secret meetings at Clonard Monastery on the ‘peace line’ in Belfast, where the 20ft-high wall had a statue of the Virgin Mary on one side and a ‘No Surrender’ mural on the other.

The IRA top command had started to realise they might not convince the British government to ‘sell out’ the wishes of nearly one million citizens in Northern Ireland at the barrel of a gun. The slogan ‘Armalite in one hand and ballot box in the other’, coined by Danny Morrison in 1981, was being called into question.

On the other hand, Peter Brooke, British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland between 1989 and 1992, admitted military defeat of the IRA was ‘difficult to envisage’.

Still, many at the top of the IRA now believed London’s insistence – communicated publicly by Brooke – that it laid no claim to the six counties other than respecting the wishes of a majority of its people.

Reid was also in regular contact with Irish taoiseach Charles Haughey. Brooke, meanwhile, set up shop in Stormont and held regular talks with Dublin politicians. Soon after taking up his post he had been briefed on the existence of a back channel between Michael Oatley, an MI6 agent, codenamed ‘Mountain Climber’, and the IRA’s hard man Martin McGuinness; he authorised it to be continued.

The word ‘clarification’ bounced back and forth in the game of semantics versus reality, the perpetual hallmark of Anglo-Irish relations. There were regular calls between Dublin wordsmith Martin Mansergh and Northern Ireland Office man John Chilcot (later to become known for overseeing the inquiry into the Iraq War) in an attempt to find common ground.

Palace coups played their part in bringing matters to a head. First, Margaret Thatcher was ousted by her party, then Haughey by his. The ‘Iron Lady’ and ‘The Boss’ were gone. In their places were the less intimidating and more amenable John Major and Albert Reynolds.

In February 1993 Major was looking over papers in the Cabinet Room when he was informed that there was a phone call for him from the IRA, possibly McGuinness himself. “The conflict is over, but we need your advice on how to bring it to a close.” Major decided to take the call seriously.

A bomb in Warrington a few weeks later, which killed two children, nearly destroyed everything, until the IRA, chastened by their own wives and mothers, confidentially apologised: they had uncontrollable hardliners too. Indeed, in October, a bungled attack on a loyalist paramilitary office above a chip shop killed nine. A retaliation Halloween attack on a Catholic pub killed eight.

But the forces of reason still rang out loud. By December, Major and Reynolds agreed what became known as the Downing Street Declaration, containing most of the points that would later be embodied in the Good Friday Agreement. The response was hesitant, but in August 1994 the IRA declared a ‘cessation of hostilities’.

It seemed Major’s gamble had paid off, even if at a rally outside Belfast City Hall in August 1995 Gerry Adams was cheered when he declared: “They haven’t gone away, you know.”

In November, US President Bill Clinton addressed another Belfast rally and announced Senator George Mitchell as his ‘special envoy’ to the peace talks.

Mitchell declared his strategy to be a twin track of talks and moves towards arms decommissioning. The two main unionist parties, the UUP and the more hardline DUP, refused to attend negotiations. Sinn Fein were refused entry. The political wings of unionist paramilitaries, however, were allowed in.

In late 1997 I sat with David Ervine, a former UVF man jailed for possession of explosives, now a member of their political wing, the Progressive Unionist Party, in a north Belfast bar. Guinness dripped from his moustache as he shared his changed views:

“Pope John Paul II is a nice old Polish bloke; it doesn’t do anybody any good going around shouting he is the antichrist.

“If you want to make peace with men with guns,” he went on, “you have to talk to those who represent the men with guns.”

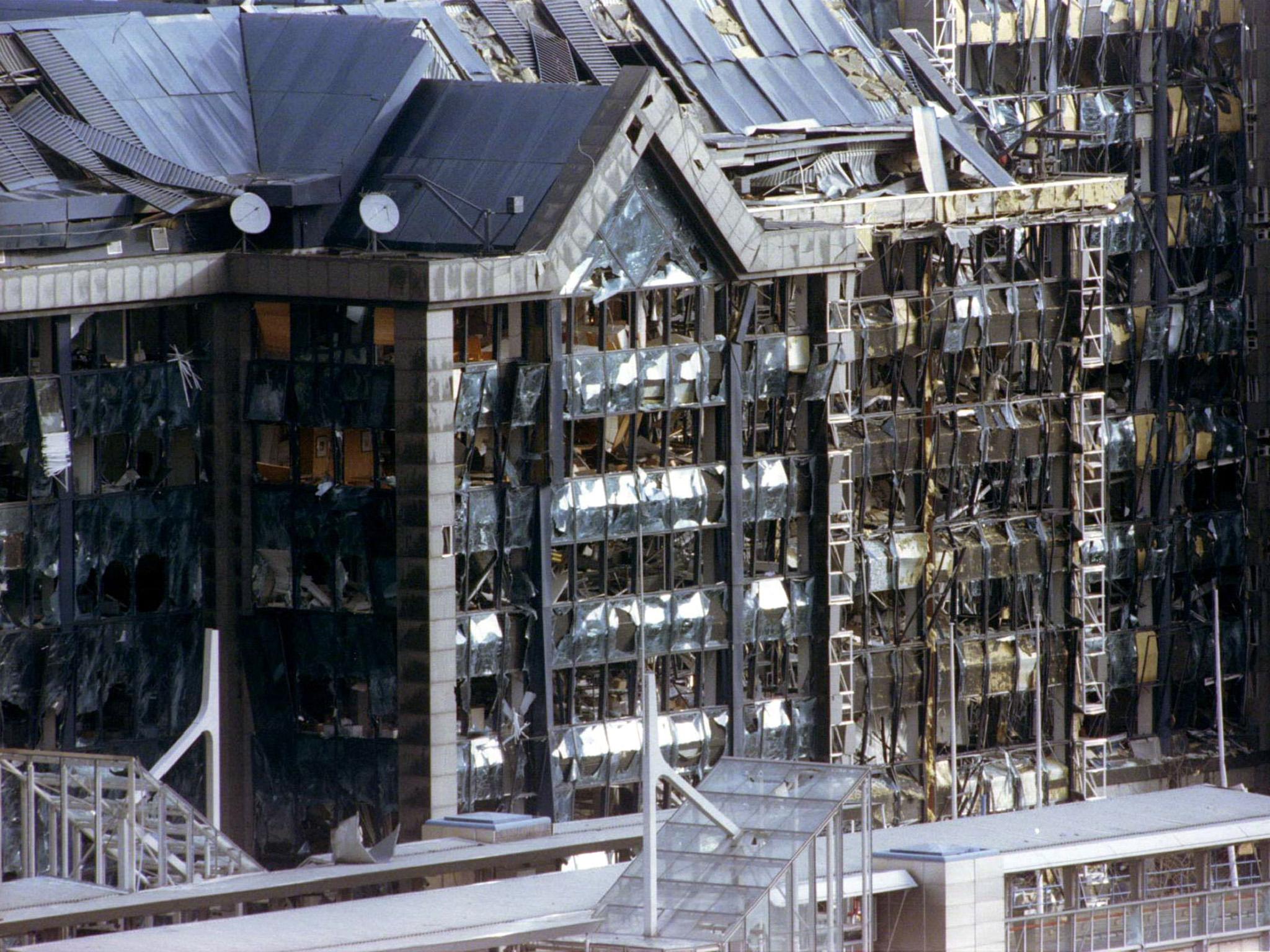

The British government had initially done that with one side but not the other. As a result, the IRA ceasefire ended abruptly on 9 February 1996 when a bomb in London’s Canary Wharf financial district killed two and wounded more than 100.

Allegations of foot-dragging were exchanged by both sides. In June, elections were held for a Northern Ireland Forum. Sinn Fein won 17 of 110 seats but refused to take up membership of what it considered a puppet British institution.

Sure enough, the day after the Forum’s first meeting, the IRA gave its clear verdict: a 1,500 kilo bomb (the biggest in Britain since the end of World War Two) wiped out a large portion of Manchester city centre. A 90-minute warning saw 75,000 people evacuated from the area, and while there were no fatalities hundreds were injured.

Again, though, a change of government put talks back on track. In May 1997 John Major handed the keys of 10 Downing Street to Tony Blair, a Labour leader who didn’t have to cope with the hard right wingers Major himself called “bastards”.

Blair’s new Northern Ireland minister Mo Mowlam issued the long-awaited invitation to Sinn Fein to join the talks. In July, the IRA announced a renewed ceasefire.

Crucially, in January 1998 Blair announced a fresh public inquiry into the 1972 Bloody Sunday killings in Derry, in which 14 unarmed citizens were shot dead by British troops. Its conclusions, finally revealed in 2010, exonerated Martin McGuinness from involvement and blamed British paratroopers for firing first.

Compromises paid off. A legally binding agreement, involving both British and Irish governments and echoing the 1993 Downing Street Declaration, was at last on the cards. The wording was designed to be a classic agreement to differ, to promise everything to everyone.

The key elements were a mutual renunciation of violation, and assurances that Northern Ireland would remain part of the UK as long as a majority of its citizens wanted it to – but could in principle become part of the Irish Republic if a majority desired it in the future.

The provisions were put to referendums on both sides of the border. In the Republic, more than 94 per cent of a 56 per cent turnout voted ‘yes’, in the north 71 per cent voted ‘yes’ on a turnout of 81 per cent. There was no official breakdown of the ethnic pattern in the north; independent observers reckoned it was overwhelming in republican circles but marginal among unionist voters.

Of Northern Ireland’s nine political parties, eight signed up to the agreement. Only one, the DUP, refused (a fact Theresa May might have missed in 2017 when she welcomed the party as an ally to prop up her minority government).

Ireland amended its constitution to remove the claim that the territory of the state was the ‘whole island’. In return Britain repealed the symbolic but obsolete 1920 Government of Ireland Act, which still nominally implied similar territorial claims.

The European Union ploughed money into north-south Irish infrastructure, including a motorway from Dublin to Belfast. The single market and customs union meant border posts disappeared, and so did the armed men who guarded them.

The early days were difficult. The old ‘moderate parties’ – the UUP and SDLP – initially dominated the new Northern Ireland Assembly, including by taking up the roles of first and deputy first minister. But after arguments broke out in 2001, the assembly was ultimately suspended by Westminster and Northern Ireland reverted to direct rule from London until a new agreement and the Assembly’s restoration in 2007.

This time, as David Ervine had predicted, the real power brokers were to be found in the driving seat: the DUP veteran firebrand Ian Paisley and ex-IRA man Martin McGuinness.

Against all odds, they not only agreed to work together but found points in common to the extent that they became something like friends, nicknamed ‘the Chuckle Brothers’. It was everything and more than the script writers of the Good Friday Agreement had dared dream of.

Decommissioning of weapons, overseen by two American politicians and two generals, one Canadian, one Finnish, went on until 2005, by which time the international committee reckoned the IRA had done away with an armoury that included some 1,000 rifles, three tonnes of Semtex, and 20-30 heavy machine guns.

In the current Brexit context it is interesting to consider how British membership of the Euro currency – to which Ireland of course signed up – would have meant an even less obvious border between north and south.

It wasn’t to happen though: British politicians treated the issue as done and dusted, and forgot the price.

There is a belief among some Ulster Unionists – just as there is among many Brexiteers – that any risk is worth taking, any outcome acceptable, as long as it achieves the sole important aim: in the former case staying in a union; in the latter, getting out of one.

Kate Hoey, the pro-foxhunting Labour MP who has more in common with the DUP than her own party, is one of those who straddles both those camps. The Antrim-born Brexit supporter has said she would “do anything” to ensure Northern Ireland remains an integral part of the UK. She also caused outrage by suggesting that if Brexit did mean a hard border in Ireland, then it would have to be the EU – and thus the Irish – who would pay for it (on the basis that the British have no desire to erect one).

Hoey and others like her give the strong impression of being dyed-in-the wool members of what was once the ‘protestant ascendancy’ who, like their forefathers, see British rule as a guarantee of superiority on their home turf.

The Good Friday Agreement questioned that assumption; Northern Ireland’s demographic shift in the years since is moving it towards breaking point. Unionist parties lost their outright majority at Stormont in Assembly elections just over a year ago. How long will it be till a majority of voters in Northern Ireland would prefer to see their future as part of Ireland, not the UK?

Set against this backdrop, Brexit looked to many unionists like locking a fire safety door.

That classic guide to British history up to 1918, Sellar’s and Yeatman’s ‘1066 and all that’, declared: “Gladstone tried all his life to guess the answer to the Irish question. Unfortunately, whenever he was getting warm, the Irish secretly changed the question.”

This time it is the British who have changed the question.

And nobody knows the answer.

Northern Ireland – a brief history

The Northern Ireland we know today was born in 1920 as part of a solution to long-running Irish ‘home rule’ demands, by creating two separate jurisdictions on the island, both still within the UK.

It was a selective gerrymandering designed to perpetuate the rights of a pro-British, mainly Protestant ‘ascendancy’ within six of the nine counties of the historical province of Ulster, while giving discrete home rule to the south.

It was not just too little too late, but way past its sell-by date. The scheme had been thrown into chaos by the First World War, the 1916 Easter Rising and its bloody suppression, then Sinn Fein’s 1918 landslide election and declaration of independence.

The status of the ‘six counties’ was a major factor in the ensuing civil war over the new country’s status. But the deal survived and an imposing neo-classical parliament building was erected at Stormont on the outskirts of Belfast.

Within their new Northern Irish fiefdom, with its built-in two-thirds majority rights, the Protestant-dominated government for the next 40 years oversaw a regime which frequently discriminated against the pro-Irish, largely Catholic minority. Prejudice was evident in housing, employment and voting rights, among other areas.

The status quo was maintained by an almost exclusively Protestant armed police force that gloried in its ‘Royal’ Ulster Constabulary title and had a paramilitary wing known as the ‘B-Specials’, used against street riots in the 1930s and in the suppression of an IRA campaign in the 1950s.

After renewed civil rights marches in the late 1960s led to further riots, brutally put down, regular British troops were sent to Northern Ireland and the ‘Specials’ were disbanded.

A split within the IRA in 1969 had created the more militant ‘Provisional’ wing, which began a violent campaign both in Northern Ireland and mainland Britain. Stormont’s response was internment without trial and a declaration that it was “at war”.

In January 1972 British soldiers shot dead 13 people in (London)Derry, which would become known as Bloody Sunday. In response the British embassy in Dublin was burnt down. Two months later direct rule from London was imposed on Northern Ireland.

Unionists at first considered this a blow but came to realise direct rule actually reinforced the province’s British status. The IRA stepped up its campaign, leading to a virtual civil war, with British troops considered to be on the side of the unionists.

The death toll on both sides of the Irish Sea soared into thousands, with no end in sight. It was against that background that forces of sanity plucked the Good Friday Agreement seemingly from nowhere, persuading both sides that this was the only way to ensure peace and security for the foreseeable future.

But the foreseeable future is hostage to demographics. In the 2017 elections, after the polarising Brexit vote, the combined unionist lobby lost their majority for the first time. The hardline DUP lost 10 seats, talking a total of 28, just one more than Sinn Fein.

The Good Friday Agreement’s promise to both sides that Northern Ireland’s future would be determined by the wishes of the majority may eventually point towards a vote for Irish unity.

As things stand, few would see the point of posing such a potentially explosive question. But Brexit and the possibility of a ‘hard border’ between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic could put all sorts of options back on the table.

Credit: Source link