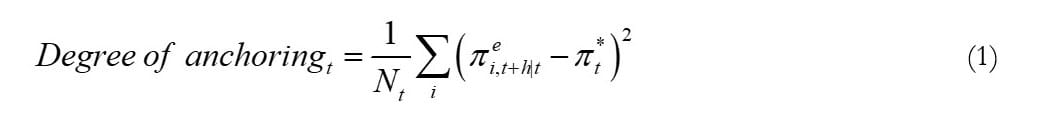

Following the previous discussion, we propose the following measure to capture the extent of inflation expectations’ anchoring at the individual level:

where  denotes the inflation forecast of individual made at time for horizon

denotes the inflation forecast of individual made at time for horizon![]() are the number of survey respondents at time , and

are the number of survey respondents at time , and![]() denotes the inflation target at time .

denotes the inflation target at time .

The measure in (1) relates to the variability of inflation forecasts and is the average deviation (or distance) of the individual inflation forecasts from the inflation target. The intuition behind this measure is that the degree of anchoring of inflation expectations is improving (worsening) as this average deviation becomes smaller (larger). In the extreme, when this deviation equals zero, then each individual reported forecast coincides with the inflation target.

As shown in the appendix, the measure in (1) can be decomposed as follows:

where ![]() denotes the consensus forecast given by the average of the

denotes the consensus forecast given by the average of the ![]() individual forecasts,

individual forecasts, ![]() . That is, our proposed anchoring measure is a combination of two subcomponents that each capture aspects of forecast behavior associated with expectations’ anchoring. The first subcomponent is the deviation (or distance) between the consensus forecast and the inflation target. The second subcomponent is the dispersion of individual forecasts—the average deviation (or distance) of the individual forecasts from the consensus forecast—and represents a standard measure of disagreement. As previously discussed, well-anchored inflation expectations are associated with forecasts that are close, on average, to the inflation target and close to each other (low disagreement). This condition requires each subcomponent in (2) to be small.

. That is, our proposed anchoring measure is a combination of two subcomponents that each capture aspects of forecast behavior associated with expectations’ anchoring. The first subcomponent is the deviation (or distance) between the consensus forecast and the inflation target. The second subcomponent is the dispersion of individual forecasts—the average deviation (or distance) of the individual forecasts from the consensus forecast—and represents a standard measure of disagreement. As previously discussed, well-anchored inflation expectations are associated with forecasts that are close, on average, to the inflation target and close to each other (low disagreement). This condition requires each subcomponent in (2) to be small.

There are several attractive features of (2) worth highlighting. While the deviation of a consensus forecast from an inflation target and forecaster disagreement each describe important aspects of forecast behavior, studies using these objects as measures of expectations’ anchoring typically examine them on an individual basis. As Bems et al. (2021) note, this latter consideration is problematic because neither proposed measure is sufficient for capturing the full extent of anchoring. For example, a set of inflation forecasts could be highly dispersed but have an average value equal to the inflation target. Although expectations would look strongly anchored from the perspective of the alignment between the consensus forecast and the target, there would be significant forecaster disagreement. An example at the other extreme would be a set of identical inflation forecasts centered at a value far away from the target. Although expectations would look strongly anchored from the perspective of forecaster disagreement, there would be notable divergence between the consensus forecast and the target. Consequently, an advantage of (2) is that it incorporates two dimensions of forecast behavior and generates a measure of expectations’ anchoring that is broader in coverage and more robust.

Related to the previous point is the issue of how to combine alternative measures of inflation anchoring. The measure in (2) is simply additive in the two anchoring subcomponents and does not involve the use of transformations or arbitrary combination schemes. This contrasts with Bems et al. (2021), who also recognize the disadvantages of analyzing anchoring measures separately but attempt to remedy this shortcoming by constructing a summary index that averages across a standardized transformation of each measure. While this approach may be reasonable, other weighting schemes can be selected that would generate different summary indexes and thereby make the ability to draw reliable conclusions about the behavior of expectations’ anchoring challenging.

The decomposition in (2) also provides insights into the sources for movements in the anchoring of inflation expectations and the role of monetary policy. The announcement of an explicit quantitative inflation target and enhanced central bank credibility should act to strengthen expectations’ anchoring by improving the alignment between the consensus forecast and the inflation target. In addition, greater transparency and improved communication about the central bank’s forecast, its reaction function, and the course of monetary policy can also act to strengthen expectations’ anchoring by reducing disagreement across forecasters, though this consideration is likely more relevant for a longer-run outlook for inflation than it is for a five-year outlook.

Taken together, we argue that our anchoring measure provides a more comprehensive indicator of expectations’ anchoring than existing measures. We apply this measure to data on forecasters’ expectations of US inflation over the last decade to evaluate the effects of events and episodes that may have exerted a meaningful influence on the degree of anchoring. In addition to the 2012 announcement of a 2 percent target for PCE price inflation, the FOMC announced a switch to a flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT) regime in August 2020. There was also a marked slowdown in inflation over the 2015–2016 period and the surge in inflation starting in spring 2021. While we restrict our analysis to US data during a low-inflation environment, the availability of cross-country data during high-inflation episodes offers further, and perhaps even more compelling, opportunities for the application of our anchoring measure.

Inflation Expectations and the Evolution of Anchoring Since 2012

To construct the overall anchoring measure in (1) and the anchoring subcomponents in (2), we focus on the expectations of professional forecasters about PCE inflation from the SPF conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Our analysis considers the point predictions at a five-year horizon and at a five-year/five-year forward horizon. In terms of the two horizons, the five-year/five-year forward horizon should act to filter out short- and medium-run movements in inflation that reflect the effects of nonmonetary factors and thereby help to isolate the longer-run movements of inflation expectations influenced by monetary policy. Nevertheless, it is useful to include data from the five-year horizon for comparison purposes.

The SPF is conducted on a quarterly basis, and the participants typically work in research institutions and the financial services industry. The SPF forecast data provide predictions for PCE price inflation at the five-year and the five-year/five-year forward horizons starting in 2007:Q1. Survey participation is very similar across the two forecast series. On average, 32 forecasters have participated at the five-year horizon per survey round, while 31 forecasters have participated at the five-year/five-year forward horizon per survey round. The SPF, like other ongoing surveys, has experienced exit and entry of respondents over time, and there are occasional nonresponses by participants to the complete questionnaire.

Our discussion initially focuses on the behavior of the overall anchoring measure in (1). Figure 1 shows the evolution of this measure at the five-year and five-year/five-year forward horizons and the quarterly (annualized) growth rate of the PCE index from 2011:Q1 to 2023:Q2; note that the last observation for latter series is currently not available because of publication lags.

Credit: Source link