What is economics all about? Ask a person in the street and the most likely answer will be along the lines of “economics is about money, earning money, something similar to business and finance”. But economics is more than just the study of money – there is a whole other side of economics that many people have never thought of. It is time we spread this message to attract more students, especially women and those from minority backgrounds, into economics.

A lack of diversity among economists has serious consequences for society. A survey of US economists found that the gender mix of economists could affect the nature of policy advice they provide.

In Australia, more than half of university economics students are in the top quarter of socio-economic status, with only about 10% in the bottom quarter. The low proportion of women, minorities and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds in the field of economics affects social problems we should all care about.

Read more:

What economics has to say about same-sex marriage

Economics can help patients find the right kidney donors or match foster children with the most suitable parents. When you do a Google search or use wireless internet, have you ever thought of the integral part that auction theory, a subfield of economics, plays in today’s digital age?

What about the most important issues facing humanity today? Media articles portray an inaccurate picture when they say that young people care more about social issues and the environment than about the economy. Without economics, none of these social and environmental issues can be tackled effectively.

Various specialisations of economics (including public, political, environmental, health, labour, cultural, social welfare, gender and development economics) analyse social issues and design testable solutions and policies for major problems of our times. This includes issues such as climate change, inequality, poverty and immigration.

Read more:

Finkel’s Clean Energy Target plan ‘better than nothing’: economists poll

Society has evolved into an economy. This means we need economic literacy to remain politically and socially informed. The problem begins with getting students into the economics pipeline.

How does an image problem affect the pipeline?

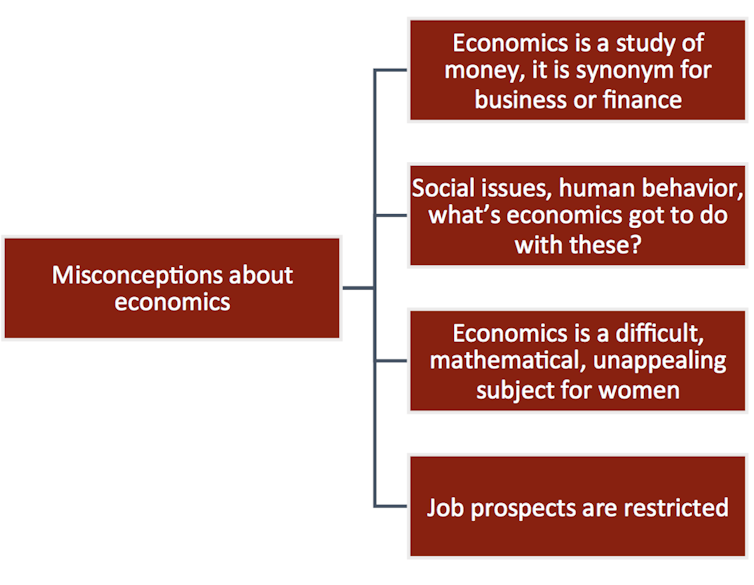

The widespread misconception that economics is essentially business and commerce creates a major hurdle to attracting students into economics. Since high schools introduced business studies in 1991, enrolments in Year 12 economics have fallen by almost 70%.

The lack of female participation in high school economics is equally stark. A 2016 study for the Reserve Bank found only about one-third of Year 12 economics students were female in 2016, down from around half 25 years ago. At Australian universities, women account for between 25% and 45% of undergraduate economics students.

Low female participation in economics at school flows on to a lack of women in economics, especially in academia. Less than 10% of economics professors at Group of Eight universities are women.

Too few high schools teach economics. Even when it is taught, its importance in solving social issues is neglected. Most high school students don’t get to know what an economist actually does and what the potential of economics can truly be.

Moreover, economics is offered mostly in private and boys’ schools. That helps explain why mostly students from a certain gender and socioeconomic background choose it as their career. This contributes to the lack of diversity in economic leadership and the related consequences for public policy and business decisions.

Paul Morse/White House Archives, CC BY

Read more:

What the Nobel Prize tells us about the state of economics

Another misconception about economics is that it is a difficult and mathematical subject, which women cannot succeed in or would not enjoy studying. In any case, there is no evidence that women are worse than men in mathematical subjects, including economics. On the contrary, several studies document the stereotype threat to the performance of women in these subjects.

Finally, the ambiguity of career paths for economics graduates is an important factor in the pipeline problem. If you study law, you become a lawyer. If you study medicine, you become a doctor. What occupation do you get as a graduate of economics?

Most young people are not able to answer this question. Having a clear idea of job prospects is crucial for students, especially those from certain demographic groups, when choosing a university degree.

Author provided

Read more:

How and why economics is taking over sports

How can we fix economics’ image problem?

Unlike declining enrolments in STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, maths), the decline in economics enrolments, especially by women, has received little public attention. The remedy probably starts with expanding the number of high schools that teach economics. The curriculum also needs to be redesigned to highlight the relevance of economics to our daily lives and, more broadly, for resolving social problems.

Universities can also do a lot more. Initiatives that can help include organising high school events where speakers talk about social issues through an economics lens, choosing female speakers for these events, and preparing career guides that explain the wide range of paths that economists can follow.

Recently, steps have been taken to increase women’s participation in economics both at universities, such as the Women in Economics program at the University of Adelaide and Women in Economics Hackathon at the University of Queensland, and nationwide (Women in Economics Network). These initiatives promise the start of a new era for the pipeline problem of women in economics in Australia.

Yet a lot remains to be done to resolve the image problem of economics. Portraying a more accurate and inclusive image of economics in the media would be an effective step in this direction.

Read more:

300,000 women are missing from economics

Credit: Source link