A few years ago I started conducting interviews with over 100 people about their online dating experiences. I wanted to know how people presented themselves on their profiles, perceived other users on the platforms, and made decisions about whom to date.

My participants included single people trying to find “the one,” some simply looking to casually date and hook up, and others in polyamorous or open relationships who were seeking to expand their network of lovers.

Things were going well, with a steady stream of data coming in – right up until the pandemic hit. Lockdown upended the normal ebbs and flows of dating life.

So I switched gears and decided to focus on how the pandemic had influenced the dating lives of my participants. I sent out quarterly surveys and interviewed subjects over video chat, the phone and social media.

One finding soon emerged: People practicing polyamory were facing a totally different set of pandemic-related dilemmas than those who practice monogamy.

At the same time, their experience navigating the complexities of having more than one partner had put them at a particular advantage when it came to managing pandemic-specific dating issues.

A polyamory primer

“The Smart Girl’s Guide to Polyamory” defines polyamory – often shortened to “poly” – as “engaging in multiple romantic relationships simultaneously with full knowledge and consent of all parties.”

Counter to perceptions and myths, poly isn’t strictly about sex, nor is it a form of cheating, which constitutes nonconsensual nonmonogamy. Rather, it’s relationship-focused. Everyone involved is privy to the arrangement.

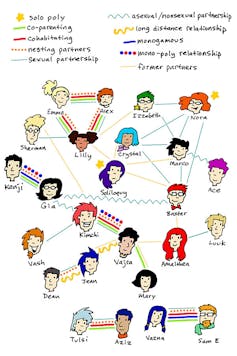

Relationship networks – also known as “polycules” – can be complex and interconnected.

There are numerous forms: hierarchical networks place certain relationships over others. Then there are nonhierarchical arrangements, which don’t prioritize or place couples at the center. In solo poly, individuals prefer autonomy and give all romantic partners equal standing.

With all of this variation, a lexicon unique to poly relationships has emerged. A “metamour” refers to your partner’s partner, and “compersion” refers to a sense of happiness you feel for a partner who is happy with another partner.

Within a hierarchical configuration, poly people use terms like “primary” and “secondary” partner, whereas many solo poly people reject language that characterizes a tiered system. They prefer to call their significant lovers “anchor partners.”

These arrangements are more prevalent than you might think.

A 2016 representative study of adults in the U.S. found that 21% reported participating, at some point in their life, in a relationship defined as one in which “all partners agree that each may have romantic and/or sexual relationships with other partners.” A CBSN documentary suggests that between 4% and 5% of adults living in the U.S. are currently practicing consensual nonmonogamy, while a 2018 study estimates that at least 1.44 million adults in the U.S. fall within the category of polyamorous.

Sociologist Elizabeth Sheff has noted that these statistics likely underestimate the prevalence of these arrangements, because many polyamorists are “often closeted and fear discrimination on account of the stigma often attached to non-traditional relationship models.”

Polycules get put on pause

For single people, finding at least one partner has been hard enough during the pandemic. But for those accustomed to juggling multiple relationships, the pandemic has forced them to rethink their expectations for dating altogether.

On a March 2020 episode of his “Savage Lovecast,” sex columnist Dan Savage declared that “poly is canceled” because of the pandemic, adding that “monogamy is where it’s at these days.”

In my study, some participants who identify as polyamorous – all of whom I refer to with pseudonyms – seemed to agree with Savage’s assertion. They told me that they were “monogamous for now,” though not out of preference, but by circumstance.

In July, Bald Guy, a 50-year-old married poly man, reported that his newest relationship seemed “to be fizzling.”

“I’ve met with her outside at a social distance of about 10 feet three times since the lockdown,” he added. “We have only done video chat once. Messages are dwindling. She is partnered up monogamously with one of her partners, too.”

Lance, a 61-year-old poly man, simply cited a lack of opportunity. “I would like to ‘date cautiously,’” he told me, “but the mechanisms to find others are not functioning as they did prior to the pandemic. I think many people have ‘gone to ground’ in military parlance.”

Aristotle, a 56-year-old solo poly man, reported a newfound openness to monogamy. Trying to manage a poly lifestyle during the pandemic had been exhausting.

“This climate,” he said, “has just put way too much stress on my prior life.”

I noticed how people in Facebook groups devoted to poly relationships were discussing how stay-at-home orders advantaged some relationship types over others. Those with “nesting partners” – a live-in partner or partners – were automatically granted the right to maintain their relationships during lockdown.

Meanwhile, those living apart were expected to cut off connection for an indefinite period.

Pulling from the existing toolkit

In my study there were also participants who have tried to retain some semblance of their preexisting relationships.

Because open communication is an important element of poly relationships, it’s common to talk about sexual health, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and testing.

This experience has served poly people well when it comes to talking about COVID-19 testing and social contacts.

As Dandelion, a 20-year-old nonmonogamous, nonbinary person, explained, “I think having to navigate STI conversations before COVID prepared me a lot to have those conversations.”

A 64-year-old poly man who goes by Special Sauce made a similar point regarding the coronavirus: “Conversations about risk and exposure to SARS-CoV-2 are just like conversations about safe sex and testing.”

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve heard about families and friends forming “pods” or “bubbles,” limiting maskless interaction to a small, predetermined group to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

For many poly people, their pods and polycules do not neatly overlap. Some live with roommates or family members while their partners live elsewhere. Finding ways to connect with partners without endangering members of their pod has proved to be challenging.

Curio, a 38-year-old solo poly woman, reported that members of her household changed the rules in August when they realized they “needed to set people up to make informed and harm-reduction-based decisions, instead of saying a flat ‘no’ to everything.” They agreed that housemates would be permitted to connect with others beyond their bubble if the person they were seeing had received a negative COVID-19 test and quarantined until meeting.

Suedonym, a 35-year-old poly woman, described similar negotiations to protect an immune-compromised pod member; the group decided that “a person needs to be quarantined and asymptomatic for two weeks before being allowed into the pod.”

Webs become unwieldy

And yet the risks could be daunting, with some polyamorous arrangements reflecting a sprawling web of contacts.

Kimchicuddles, Author provided

In May, Poly Slut, a 45-year-old solo poly man, sketched a social network map of his and his roommate’s interconnected polycules. He quickly realized that it would have been impractical to adhere to safety guidelines, so in the end he put some relationships on hold to reduce risk.

In January, Bubbly Brunette, a 47-year-old married, poly woman, decided, sadly, to end “all in-person sleepovers with my boyfriend because … he chooses to spend indoor time unmasked with people that he and his other partner are casual acquaintances with and I’m not.”

A 66-year-old nonmonogamous man who goes by Seadog described a similar shift with one of his regular partners.

“I was widening my sphere of contacts a little,” he explained, “and that made her nervous.”

Therein lies the core dilemma for people in polyamorous relationships. Because of the complexity of pods and polycules, the challenges of keeping romantic relationships alive are even greater. Until life gets back to normal, compromises constantly need to be made.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

Credit: Source link