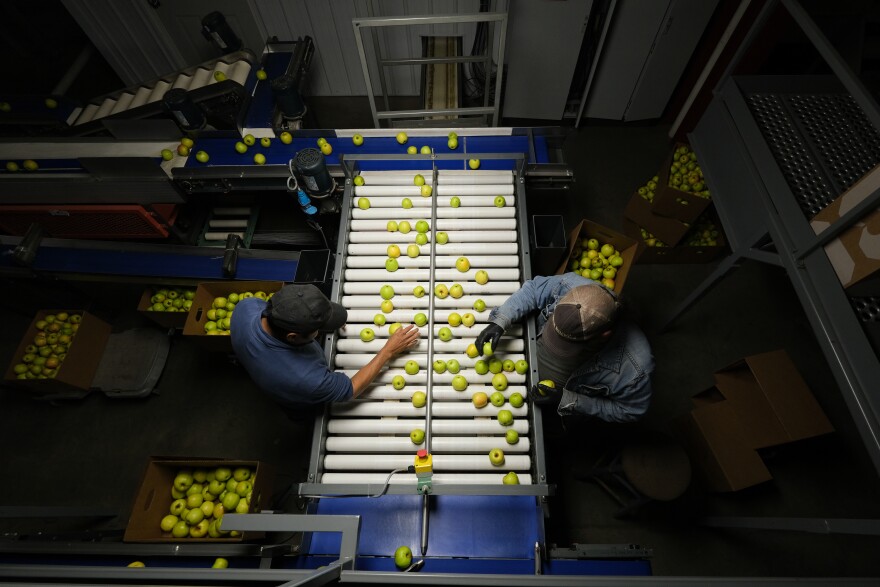

It’s getting late in the harvest season in Berkeley County, West Virginia and Carla Kitchen’s team is in the process of hand-picking nearly half a million pounds of apples. In a normal year, Kitchen would sell to processors like Andros that make applesauce, concentrate, and other products. But this year they turned her away.

“Imagine 80% of your income is sitting on the trees and the processor tells you they don’t want them,” Kitchen says. “You’ve got your employees to worry about. You’ve got fruit on the trees that need somewhere to go. What do you do?”

For the first time in 36 years, Kitchen had nowhere to sell the bulk of her harvest. It could have been the end of her business. And she wasn’t the only one. Across the country, growers were left without a market. Due to an oversupply carried over from last year’s harvest, growers were faced with a game-time economic decision: Should they pay the labor to harvest, crossing their fingers for a buyer to come along, or simply leave the apples to rot?

/ Alan Jinich

/

Alan Jinich for NPR

Bumper crops, export declines and the weather have contributed to the apple crisis

Christopher Gerlach, director of industry analytics at USApple, says the surplus this year was caused by several compounding factors. Bumper crops have kept domestic supply high. Exports have declined 21% over the past decade, a symptom of retaliatory tariffs from India that only ended this fall.

Weather also played a role this year as hail left a significant share of apples cosmetically unsuitable for the fresh market. Growers would normally recoup some value by selling to processors, but that wasn’t an option for many either – processors still had leftovers from last year sitting in climate-controlled storage.

“Last year’s season was so good that the price went down on processors and they said, ‘let’s buy while the buyings good,’ ” Gerlach says. “These processors basically filled up their storage warehouses. It’s just the market.”

While many growers in neighboring states like Maryland and Virginia left their apples to drop. Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia was able to convince the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to pay for the apples produced by growers in his state, which only makes up 1% of the national market.

A relief program in West Virginia donated its surplus apples to hunger-fighting charities

This apple relief program, covered under Section 32 of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1935, purchased $10 million worth of apples from a dozen West Virginia growers. Those apples were then donated to hunger-fighting charities across the country from South Carolina and Michigan all the way out to The Navajo Nation.

A nonprofit called The Farmlink Project took care of more than half the state’s surplus – 10 million pounds of apples filling nearly 300 trucks.

/ Alan Jinich

/

Alan Jinich for NPR

Mike Meyer, head of advocacy at The Farmlink Project, says it’s the largest food rescue they’ve ever done and they hope it can serve as a model for their future missions.

“There’s over 100 billion pounds of produce waste in this country every year; we only need seven billion to drive food insecurity to zero,” Meyer says. “We’re very happy to have this opportunity. We get to support farmers, we get to fight hunger with an apple. It’s one of the most nutritional items we can get into the hands of the food insecure.”

At Timber Ridge Fruit Farm in Virginia, owners Cordell and Kim Watt watch a truck from The Farmlink Project load up on their apples before driving out to a food pantry in Bethesda, Md. Despite being headquartered in Virginia, Timber Ridge was able to participate in the apple rescue since they own orchards in West Virginia as well. Cordell is a third-generation grower here and he says they’ve never had to deal with a surplus this large.

“This was unprecedented territory,” Watt says. “The first time I can remember in my lifetime that they [processors] put everybody on a quota. I know several growers that just let them fall on the ground. … The program with Farmlink has really taken care of the fruit in West Virginia, but in a lot of other states there’s a lot of fruit going to waste. We just gotta hope that there’s funding there to keep this thing going.”

/ Alan Jinich

/

Alan Jinich for NPR

At the So What Else food pantry in Bethesda, Md., apple pallets from Timber Ridge fill the warehouse up to the ceiling. Emanuel Ibanez and other volunteers are picking through the crates, bagging fresh apples into family-sized loads.

“I’m just bewildered,” Ibanez says. “We have a warehouse full of apples and I can barely walk through it.”

“People in need got nutritious food out of this program. And that’s the most important thing”

Executive director Megan Joe says this is the largest shipment of produce they’ve ever distributed – 10 truckloads over the span of three weeks. The food pantry typically serves 6,000 families, but this shipment has reached a much wider circle.

“My coworkers are like, ‘Megan, do we really need this many?’ And I’m like, yes!” Joe says. “The growing prices in the grocery stores are really tough for a lot of families. And it’s honestly gotten worse since COVID.”

Back in West Virginia, apple growers, government officials, and Farmlink Project members come together in a roundtable meeting. Despite the existential struggles looming ahead, spirits were high and even some who were skeptical of government purchases applauded the program for coming together so efficiently.

/ Alan Jinich

/

Alan Jinich for NPR

“It’s the first time we’ve done this type of program, but we believe it can set the stage for the region,” Kent Leonhardt, West Virginia’s commissioner of agriculture says. “People in need got nutritious food out of this program. And that’s the most important thing.”

Following West Virginia’s rescue program, the USDA announced an additional $100 million purchase to relieve the apple surplus in other states around the country. This is the largest government buy of apples and apple products to date. But with the harvest window coming to an end, many growers have already left their apples to drop and rot.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Credit: Source link