A college degree has traditionally been a reliable pathway to the middle class. However, over the past 40 years, college tuition has significantly outpaced many families’ incomes. Consequently, too many college students, particularly those from less-advantaged backgrounds, have had to resort to substantial student loans to finance their education. Indeed, college graduates who are the first in their family to go to college are more likely to incur debt to complete their degree than their peers.

To ensure that the burden of student loans does not hinder the earnings and employment opportunities afforded by a college degree, the Biden-Harris Administration introduced the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan in August 2023. This new income-driven repayment (IDR) plan, like its predecessor, is voluntary and bases monthly student loan payments on the borrower’s earnings. However, the new formula includes adjustments such as (but not limited to) shielding more income from being used to calculate student loan payments and waiving unpaid interest at the end of each month to lower monthly payments.[1] This new plan introduces flexibility compared to previous repayment plans for those who may want to have more cash on hand earlier in their careers: a time when income levels are often lower and individuals tend to be more financially unstable.

While the immediate benefits of having more disposable income are well understood, the SAVE plan also offers significant long-term debt relief. Specifically, IDR plans forgive any remaining balances after the borrower has remained in good standing by making required payments during the repayment period (typically 20 or 25 years). Thus, by reducing total payments over the repayment period, the SAVE plan results in substantial loan forgiveness. In addition, SAVE shortens the repayment period to as few as 10 years for borrowers who have taken out $21,000 or less in student loans–generating even more rapid loan forgiveness.[2]

To summarize the complexities of SAVE, this issue brief uses the rules of the plan to simulate how the SAVE plan reduces monthly payments for a typical Bachelor’s degree holder, emphasizing the significant loan forgiveness and wealth accumulation potential offered by enrolling in SAVE. We also draw parallels between these benefits and what borrowers with different degrees can anticipate from SAVE. Furthermore, we discuss the implications of these benefits for both borrowers and the overall economy.

SAVE Plan Simulations

A standard loan repayment plan typically requires a student to repay their loan over 10 years at a fixed interest rate (most recently 5.5% for undergraduate loans) with equal monthly payments. The old REPAYE plan adjusts payments based on the borrower’s current income and extends the repayment term to up to 20 years. For the majority of borrowers, this provides more liquidity in early years than the standard plan. We focus on the benefits of SAVE compared to REPAYE, thus likely understating the benefits of SAVE compared to a standard repayment plan for most borrowers.

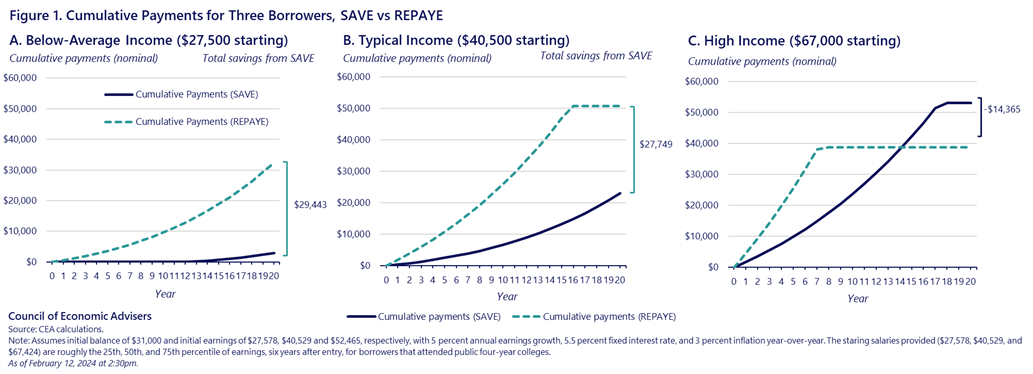

Figure 1 shows lifetime payments (in nominal dollars that are not adjusted for inflation) under the SAVE (dark blue) and REPAYE (light blue) plans for three borrower types: low-income ($27,578 starting salary), typical ($40,549 starting salary), and high-income ($67,424 starting salary). Note that this calculation treats a dollar today as equal to a dollar in ten years. We discuss the importance of accounting for the difference in timing below.

The three salaries approximate the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of initial earnings for full-time employed bachelor’s degree holders in 2022 dollars.[3] The simulation assumes 5% annual earnings growth. This means that, by year 20, the low-income borrower who starts with a salary of $27,578, is projected to earn nearly $70,000 annually. Similarly, the typical borrower starting at $40,549, is projected to earn upwards of $102,00 in year 20, and our high-income borrower’s annual earnings will increase from $67,424 to over $170,000 in year 20.[4] Each simulation assumes a $31,000 loan balance (equal to Federal student loan borrowing limit for dependent undergraduate borrowers) and a 5.5% loan interest rate.[5]

Loan Forgiveness Embedded in SAVE

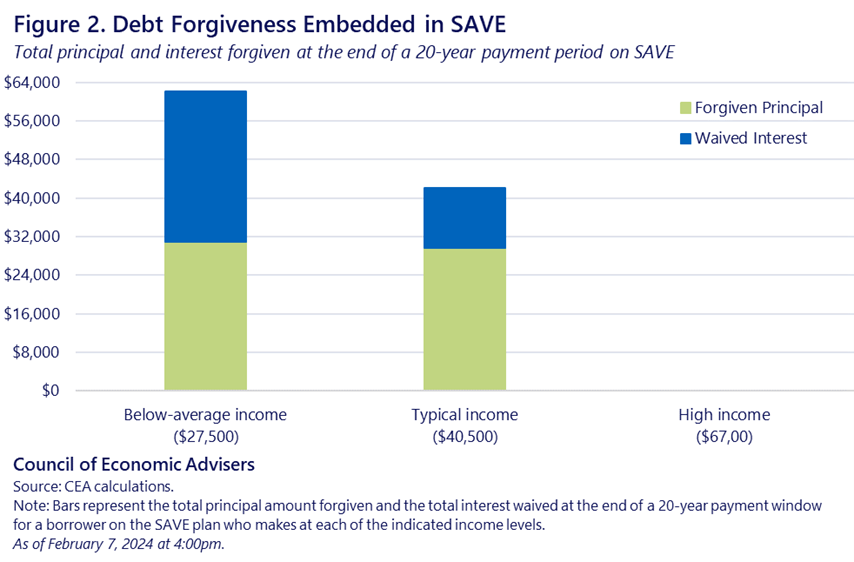

Before comparing SAVE to REPAYE, we first discuss the loan forgiveness features embedded in SAVE. Under SAVE, monthly payments are based solely on a borrower’s income and family size, ensuring that they owe only what they can afford. For the low-income borrower in Panel A of Figure 1, for example, initial payments are zero until their income increases. During this period, unpaid interest is subsidized and the principal remains unchanged. In other words, as long as the borrower makes their monthly payment, they will never see their loan balance grow. We explain SAVE’s interest subsidy (herein referred to as the interest waiver) further in this CEA blog. As income rises, payments for the low-income borrower increase to approximately $50 per month in year 20; at this point the borrower is earning close to $70,000 per year. After 20 years, when all remaining debt is forgiven, the low-income borrower has paid roughly $3,000 cumulatively towards their loan balance. This borrower sees significant savings under SAVE, through substantial interest benefits (roughly $31,000) and 100% of their principal forgiven (see Figure 2).

Borrowers who make roughly the median starting salary for a BA holder ($40,500 in year one) make higher payments than low-income borrowers due to their higher income, but similarly receive substantial forgiveness under SAVE. The median borrower (hereby referred to as the “typical borrower,” and as seen in Figure 1, Panel B), makes low monthly payments in early years, during which time they pay little interest. As income rises, payments begin to cover interest and a small amount of principal. Ultimately, the typical borrower has about $12,000 of interest payments waived and upwards of 95% of their principal forgiven under SAVE. The higher a borrower’s income, the less forgiveness they stand to gain from SAVE. The high-income borrower from Panel C, for example, has initial payments that cover all interest and some principal. Because there is no cap on payments, if they opt in to the SAVE plan, they end up paying off their full balance in 17 years (as opposed to 10 years for a standard loan). The extent to which paying the loan off over 17 vs 10 years is desirable depends on the specific borrower, their risk aversion and how much they value monthly liquidity.

Reduced Debt Cost Under SAVE Relative to REPAYE

So far, this brief has focused on the forgiveness embedded in SAVE, and it is important to note that SAVE offers more generous overall savings than REPAYE, (for example, interest payments are not fully subsidized under REPAYE).[6] However, the most straightforward way to evaluate the benefits of the new plan versus the old is to compare lifetime payments under the two.

Under both IDR plans, monthly payments rise with income, however, Figure 1 demonstrates that the SAVE plan significantly reduces monthly payments for most borrowers, with a notable impact on low- and middle-income individuals. Over 20 years, the low-income borrower’s cumulative payments (not inflation adjusted) under SAVE are less than 10% of what they would have been under REPAYE–with initial monthly payments of 0 under SAVE compared to roughly $80 under REPAYE. Because the outstanding balance is forgiven after 20 years, around 90% of the total loan cost is forgiven compared to REPAYE. This is indicated by the $29,443 difference in cumulative nominal payments indicated in Figure 1. Indeed, single borrowers making under roughly $17 per hour will be protected from the burden of monthly payments and owe $0 per month towards student debt payments.[7]

Even for those with a median starting salary for bachelor’s degree holders (roughly $40,500), SAVE considerably cuts down cumulative monthly payments (Figure 1b) – from $211 to $96 per month. Because the cumulative payments are much smaller, after 20 years these borrowers receive considerable loan cost reductions of about 55% compared to REPAYE — indicated by the $27,749 difference in cumulative nominal payments.

Our high-income borrower (Panel C), is one who receives no forgiveness (see Figure 1). Under REPAYE, this borrower would have paid off their full loan amount by year 7, with monthly payments ranging from roughly $380 at the borrower’s starting salary of $70,000 annually, to over $500 per month as the borrower’s salary grows. Compare this to the SAVE plan, where the same borrower is responsible for monthly payments of less than $150 in their first year. These monthly payment reductions offer the borrower significant liquidity month-to-month. To cover the extra interest payments associated with the longer borrowing time, however, this borrower in nominal terms (i.e., not accounting for inflation) pays more under SAVE than REPAYE—as illustrated by the $14,365 higher cumulative nominal payments (Figure 1). While this may seem undesirable, recall that enrollment in SAVE is voluntary. Borrowers preferring lower total payments but higher monthly installments might choose a different plan. Others might appreciate how SAVE spreads payments over more years, easing the monthly burden and freeing up income for other uses. Additionally, deferring payment under SAVE has a potential wealth-building effect, which we discuss next.

The Potential Wealth Building Power of SAVE: The Time Value of Money

SAVE offers considerable loan forgiveness, and there are obvious benefits to having more cash on hand to cover necessities. However, SAVE also provides sizable potential lifetime wealth benefits to borrowers due to shifting the payments further into the future (even for those who receive no loan forgiveness at all). This wealth effect is driven by the time value of money – i.e., the fact that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in five or ten years. Because of this, a higher-income borrower paying down their loan over 7 years—which is subject to less cumulative interest—could actually be more financially costly than the same borrower paying down their loan over 17 years.

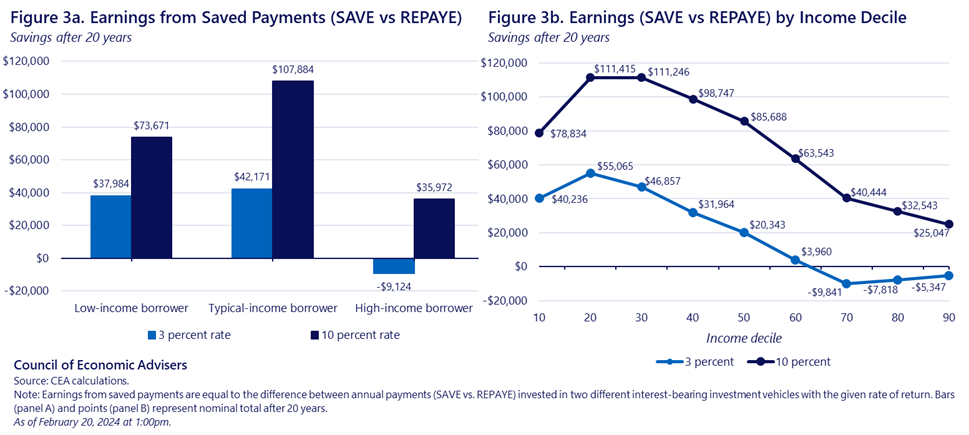

To illustrate this point, let’s see what would happen if a borrower decided to put every dollar saved by switching from the REPAYE to the SAVE plan into one of two interest-bearing investment vehicles at the end of each year. We assume a high-yield savings account with 3 percent interest and the S&P 500 stock market index fund with 10 percent annual return. While this may not be feasible for many borrowers who have little excess money to invest, this thought experiment is instructive. Figure 3a shows how much each borrower type has in savings after 20 years under two different interest rates (in both scenarios we assume that interest is compounded annually for 20 years).

For the low-income earner, the total savings on payments after 20 years was about $29,000 in nominal terms. However, when invested in an account that earns interest, this money will grow. After considering the potential interest, the low-income earner would have $38,000 more if invested in a bank account and $74,000 more if invested in the stock market in year 20 than they would have under REPAYE (see Figure 3a). Adjusted for inflation, this would be equivalent to between $21,000 and $42,000 in today’s dollars. For the middle-income earner, these calculations for the bank account and the stock market are $42,000 and $108,000 in year 20, which is between $24,000 and $62,000 today.

The high-income borrower, who makes higher nominal, cumulative payments under SAVE than REPAYE, is the most salient example of the time value of money. The saved and invested payments in the first 7 years of payment (just over $3,000 annually) can grow significantly—potentially offsetting the additional interest payments associated with a longer repayment period. While this borrower in year 20 will have less savings when put into a savings account (consistent with figure 1), they can actually have nearly $36,000 more if the savings are invested in the stock market. This is because the investment interest earned on savings in the early years can be greater than the additional loan interest. In present-day dollars, if invested in the stock market, this is equivalent to being nearly $21,000 richer today because the borrower switched from REPAYE to SAVE.

Indeed, due to the time value of money and the power of compound interest, our simulations find that the potential wealth effects associated with SAVE relative to REPAYE or a traditional loan (due to the time value of money) is positive for almost all borrowers (see Figure 3b). It is worth noting, however, that the gains associated with the stock market are risky and are not guaranteed.

What about borrowers with other degrees?

While our simulations often focus on bachelor’s degree holders, many U.S. student debt holders have different degrees. In 2019, Brookings estimated that only 29% of total student debt was held by households whose highest level of education is a BA. Graduate degree holders (who also have BAs) accounted for 56%, associate degree holders for 7%, and those without a degree for 8%. CEA analysis of the Current Population Survey shows that the 25th percentile income of bachelor’s degree holders is roughly equivalent to the median income of associate degree holders, while the median income of graduate degree holders tends to be above the median for BA holders. As such, the benefits of SAVE for sub-baccalaureate degree holders (i.e., those with some college education but no 4-year degree) are likely similar to low-income BA borrowers, while the benefits of SAVE for those with graduate degrees would be more similar to those for high-income BA borrowers, with important differences in the structure of the SAVE plan for graduate debt holders.[8] Future CEA analysis will explore the benefits of SAVE for various types of borrowers.

Under the SAVE plan, sub-baccalaureate borrowers, similar to low-income borrowers, are likely to benefit from considerable loan forgiveness. This is driven by a greater share of income being protected – resulting in lower monthly payments, increased liquidity, and lower total payments overall. In contrast, graduate student borrowers, who have higher incomes on average, are more likely to benefit from the potential wealth-building power of SAVE—driven by the time-value of money. By spreading lower payments over a longer repayment period, higher-income graduate borrowers can significantly increase their savings, as shown in Figure 3. While these difference by education level likely hold in general, it is important to note that these assumptions should be taken as exemplars given that income levels can greatly vary across and within different educational attainment levels.

Another benefit introduced by the SAVE plan is the reduction of time to forgiveness for borrowers who have taken out smaller loans to pay for college. As mentioned, the SAVE plan reduces time to forgiveness to as little as 10 years for those borrowers who have taken out $21,000 or less in student loans. This benefit is especially impactful for sub-baccalaureate borrowers, as those with no degree or an associate or certificate degree are more likely to have lower loan amounts than bachelor’s degree holders. The Department of Education estimates that roughly 85 percent of community college borrowers could be debt-free within 10 years as a result of the SAVE plan.

Non-financial economic benefits of SAVE

By reducing payments for low-income individuals and deferring payments to later life stages when disposable income is higher, SAVE lessens the financial burden (which can impact mental health) and reduces the likelihood of default. This facilitates “consumption smoothing”, making additional debt payments less likely to impact consumption and savings, particularly for young borrowers—offering future generations greater financial security and lessening the drag that student debt can have on consumption. Additionally, research shows that debt can negatively impact behaviors and attitudes, leading to sub-optimal career sorting and human capital accumulation. This can be harmful to individuals and society more broadly. The SAVE plan’s debt forgiveness and real savings can alleviate these issues, leading to benefits for individuals and communities over time.

Early Evidence of Success

As of February 20, 2024 7.5 million borrowers were enrolled in the SAVE plan. Of these, 4.3 million have a zero-dollar scheduled payments based on their income levels. Moreover, Department of Education analysis shows that borrowers enrolled in SAVE who are currently making non-zero payments are saving on average $117 per month or over $1,400 per year. This suggests that the SAVE plan is already providing increased liquidity for borrowers. Those who are unable to make payments are shielded from doing so until their income rises, while those who making payments are doing so more comfortably than before. [9]

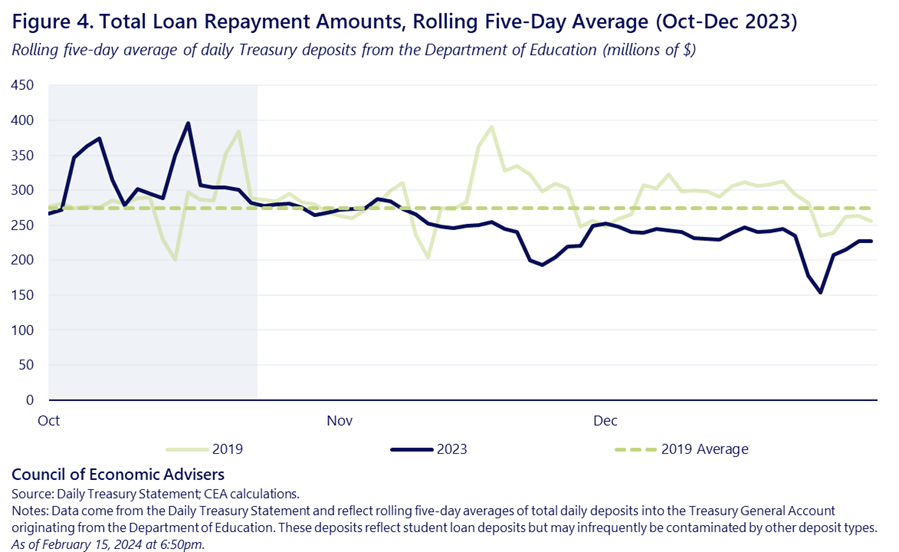

From a macro perspective, these patterns suggests that payment obligations under the SAVE plan are less likely to hinder consumption than previous IDR plans. Figure 4 shows that after a surge in payments at the beginning of the payment restart (see, for example, the shaded period), aggregate daily payments in 2023 are coming in significantly below 2019 levels. Coupled with the evidence that borrowers who have switched to SAVE are saving money on average, this suggests the potential for the SAVE plan to benefit individual borrowers and improve macroeconomic conditions.

It is worth noting that SAVE is compatible with the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) Program. After the equivalent of 120 qualifying payments, PSLF forgives loans for those in qualifying public service jobs, which includes work for government or 501(C)(3) non-profit organizations. Borrowers can benefit from SAVE’s lower monthly payment requirements and interest waivers while also pursuing loan forgiveness through PSLF.

While there is strong evidence of positive engagement with the SAVE plan, especially from those borrowers who have the most to gain, our simulations reveal that a much wider range of borrowers across income levels could benefit from enrolling in the SAVE plan. Our example of the high-income borrower shows that, even when receiving no loan forgiveness and not saving in nominal terms from switching from REPAYE to SAVE, borrowers stand to gain by smoothing payments out over time, freeing up more money in the early years of a borrower’s payment schedule, and (taking advantage of the time value of money) accumulate greater wealth over time.

Importantly, the SAVE plan also offers historically generous loan forgiveness. By reducing the time to forgiveness for borrowers who originally took out $21,000 or less in loans and protecting more of a borrowers’ income over time, the SAVE plan, compared to existing alternatives, offers deep loan forgiveness for the majority of borrowers. In short, the SAVE plan is the single most generous repayment plan ever offered in the United States, with substantial benefits for individuals and the broader economy.

[1] Note that the full SAVE regulations will go into effect on July 1, 2024, but the Department of Education has implemented three key benefits already: first, the amount of income protected from payments on the SAVE plan has risen to 225% of the Federal poverty guidelines (FPL); next, the Department has stopped charging any monthly interest not covered by the borrower’s payment; and finally, married borrowers who file their taxes separately are no longer required to include their spouse’s income in their payment calculation for SAVE. Other provisions, such as payments on undergraduate loans being cut from 10% to 5% of incomes above 225% of FPL, will go into effect in July 2024. For more information on the final implementation of the rule, see guidance from the Department of Education.

[2] As of February 2024, borrowers who borrowed $12,000 or less will receive forgiveness after making the equivalent of 10 years of payments (a 10-year repayment term). For borrowers who borrowed more than $12,000, the repayment term is one year longer for every $1,000 above $12,000 borrowed. For example, an individual who originally borrowed $13,000 could see forgiveness after 11 years when enrolled in the SAVE plan. See Federal Student Aid for more details.

[3] These are measured in 2017 and adjusted to 2022 dollars because starting salaries for BA holders are rarely measured. To capture the average starting salary for BA holders, we use survey data from National Center for Education Statistics’ Baccalaureate and Beyond (B&B) survey as well as Current Population Survey (CPS) data. The last time the B&B survey published data on characteristics of first post-baccalaureate job (including starting salary) was in 2020 for 2017 salaries.

[4] These calculations assume that the borrower in question does not expand their family size of the course of the repayment period. SAVE payments are calculated based on income and family size, and thus can change as the result of marriage and children.

[5] A $31,000 starting loan balance is equal to what a student who borrowed up to the federal limit would enter repayment with, if in-school interest accumulation was waived. The 5% annual earnings growth is derived from an analysis of student borrower income data from the U.S. Departments of Education and Treasury (see note here). The 5.5% loan interest rate aligns with the current rate for new undergraduate loans.

[6] The REPAYE plan had a more limited interest benefit, charging only 50 percent of excess interest in general, and no excess interest in the first three years of repayment on subsidized loans. SAVE expands this interest benefit, and a previous rulemaking eliminated all instances of interest capitalization, except where required by statute.

[7] This assumes $17 an hour over 2,000 hours, the equivalent of a $33,885 annual salary, which is equal to 225% of the 2024 federal poverty guidelines (Department of Health and Human Services).

[8] Graduate debt holders can be seen as standing to see potentially similar, but not identical, benefits of SAVE. It is important to note, however, that several of the terms of SAVE vary for graduate debt holders as opposed to undergraduate debt holders. First, the maximum repayment term is capped at 20 years for those with undergraduate debt, but extended to 25 years for those with any graduate debt. Next, the payment rate on graduate debt will remain 10% (compared to 5% on undergraduate only loans). Those who hold a mix of undergraduate and graduate loans will pay a weighted average between 5% and 10% of their income based on the original principal balances of the loans.

[9] It should be noted that the difference in monthly payments does not account for the compositional changes in borrower pool or the difference in default rates between 2019 and 2023. For example, a higher default rate in December 2023 than in December 2019 could skew average monthly payments if borrowers with higher monthly payment burdens are more likely to default. It is unclear if and how the average monthly payment burden of defaulters differs between 2019 and 2023.

Credit: Source link