As a high school student, Lubna Azmi had a good idea of what she wanted in a college. A campus in a city on the East Coast, for sure. A school that was strong in both majors she was considering—engineering and international studies.

For Azmi, who grew up in a working-class immigrant family in Manassas, Virginia, and would be the first in her family to attend college, financial aid was also critical. She began by researching private universities that offered strong need-based aid packages. This was nonnegotiable.

On top of that, Azmi, whose parents came to the United States from Morocco, sought a campus that was diverse—racially, ethnically, geographically, and socioeconomically—where she would encounter students from different backgrounds and have the support she needed from her college community.

Johns Hopkins checked all the boxes for Azmi, who graduated in May with degrees in sociology and international studies.

“Getting accepted to Hopkins was probably the most exciting moment of my life,” she said. “I remember thinking, ‘I can’t believe this is an option that I have.'”

Until recently, it may not have been so clear of an option.

A $1.8 billion gift from Bloomberg LP and Bloomberg Philanthropies founder, former New York City mayor, and Johns Hopkins alumnus Michael R. Bloomberg in 2018 turbocharged the university’s ability to attract and retain outstanding, high-achieving students regardless of their means.

Image caption: Lubna Azmi graduated from Johns Hopkins University in May 2023 with degrees in sociology and international studies.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Five years later, fueled by changes in admissions and financial aid policies made possible by Bloomberg’s gift, there’s been a noticeable shift on campus. Hopkins is now one of the most diverse universities among its peers socioeconomically, racially, and ethnically—and, according to several outside organizations, one of the most diverse in the country, in terms of its mix of students from different racial and ethnic groups.

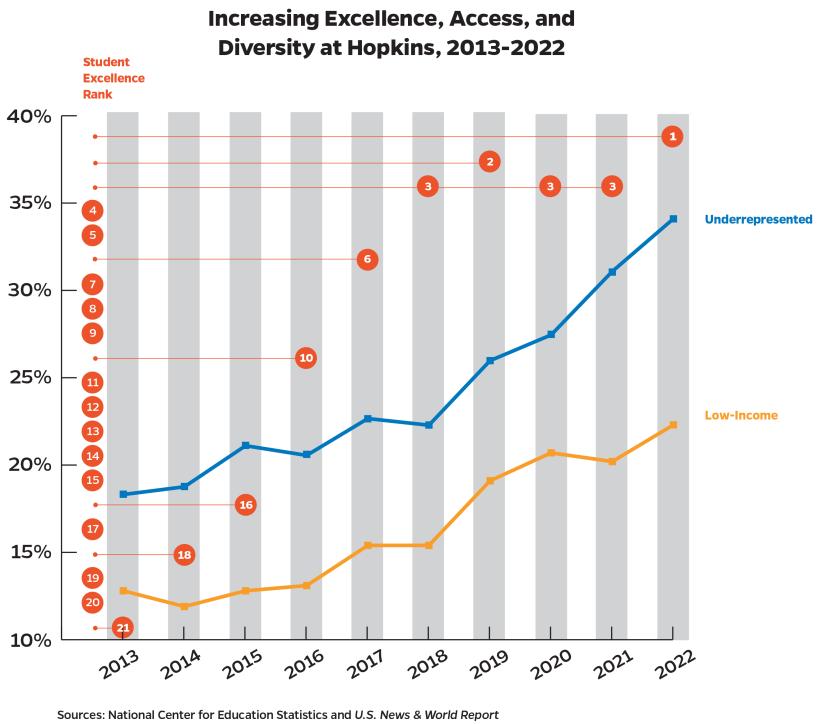

Long known for admitting outstanding students, Hopkins has become even more prestigious academically, in part because these efforts are helping to attract more highly qualified students, from all backgrounds. Over the past three years, the incoming first-year classes at Hopkins have had some of the highest ratings in the country for academic performance—and the No. 1 rating in 2022—according to data that U.S. News & World Report compiles based on standardized test scores and high school performance.

The landscape for university admissions changed dramatically in June when the U.S. Supreme Court severely limited how colleges can consider race as a factor in admissions, but Hopkins has pledged to continue pursuing a diverse student population, in approaches consistent with the new law.

“We remain deeply committed to the progress we have made and even more so to the extraordinary people who make up our student body,” JHU President Ron Daniels wrote in a message to the Hopkins community after the Supreme Court ruling. “We will, to the best of our ability, continue to reduce the barriers that stand between exceptional students and the promise of equal opportunity that forms the bedrock of our country and our university.”

Opening doors

Changes like those that have taken place at Hopkins start with a vision—that a great university should be accessible to any deserving student, that someone’s financial situation should not be a barrier to an education, and that universities are vital engines of opportunity and social mobility in a democratic society.

It’s a vision Daniels brought with him to Johns Hopkins. Since arriving in 2009, he has championed expanding opportunities and increasing the racial, ethnic, geographic, socioeconomic, and viewpoint diversity among students. Johns Hopkins himself extolled similar ideals almost 150 years ago when he imagined a university open to students based on “their character and intellectual promise” and not on their financial means.

“We knew we weren’t as diverse—racially or socioeconomically—as some of our peers, or as diverse as we should be. But the composition of our student body has changed dramatically.”

David Phillips

Vice provost for admissions and financial aid

This vision received a major boost from Bloomberg, whose 2018 gift to support undergraduate financial aid at Hopkins remains the largest-ever single contribution to a U.S. college or university.

“America is at its best when we reward people based on the quality of their work, not the size of their pocketbook,” Bloomberg wrote in a New York Times op-ed announcing his historic gift. “Denying students entry to a college based on their ability to pay undermines equal opportunity. It perpetuates intergenerational poverty. And it strikes at the heart of the American dream: the idea that every person, from every community, has the chance to rise based on merit. … My Hopkins diploma opened up doors that otherwise would have been closed, and allowed me to live the American dream. I have always been grateful for that opportunity.”

It turns out that strong principles and strategic investments are a powerful combination.

“For years, Johns Hopkins had strived to ensure that our university would be open to any high-achieving student, regardless of means, but we knew we needed to do more in order to fulfill our promise,” Daniels said. “Thanks to Mike Bloomberg’s gift, we are able to provide a Hopkins education to all students seeking one regardless of their families’ means. I am deeply moved by the progress we’ve made and the lives that have been changed as a result.”

Rising quickly

In a sector known for moving slowly, the transformations at Hopkins have been remarkably swift.

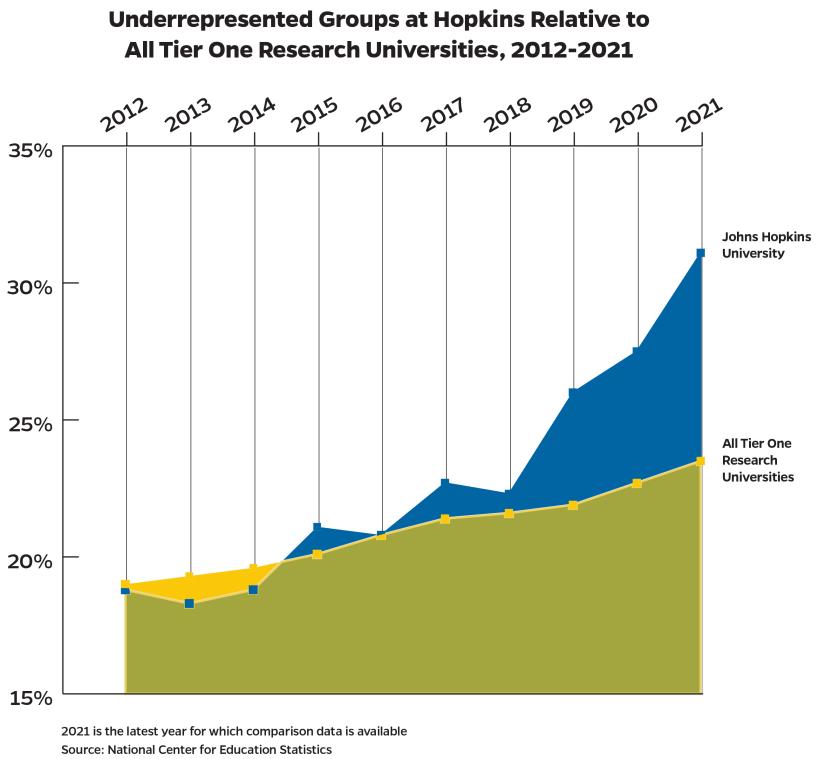

In 2018, the percentage of first-year undergraduates at Johns Hopkins from underrepresented groups was a little over 22%, just about equal to the national average for the country’s most active research universities, informally known as tier one universities. In the years since, JHU’s upward trajectory is dramatic. For the class entering in the fall of 2023, the percentage of students from underrepresented groups was 31%. Hopkins now significantly exceeds the national average for its tier one peers; in fact, it has one the most diverse undergraduate student bodies in the country, according to several national rankings.

“I love that I can walk around campus and not just see a homogeneous group of students, especially since I come from a community in which I was the only South Asian and only Muslim,” said Dua Hussain, a rising sophomore from Delaware.

Image credit: Pam Li / Johns Hopkins University

Among all 435 national universities ranked by U.S. News this fall, Hopkins was tied for the third highest diversity index. Hopkins fared nearly as well in recent diversity rankings from College Raptor (No. 11) and Niche (No. 12), which include wider selections of regional universities and small colleges. All three organizations rank the diversity of undergraduate student bodies based on the demographic mix of undergraduates and the likelihood students will meet peers from racial and ethnic groups other than their own.

“We knew we weren’t as diverse—racially or socioeconomically—as some of our peers, or as diverse as we should be,” said David Phillips, vice provost for admissions and financial aid. “But the composition of our student body has changed dramatically. And when students from all backgrounds have a positive, well-rounded experience here, and they get that word out, it gets other students interested in attending. Then we attract an even more diverse applicant pool, and it gives us even more choices of high-performing students from all backgrounds.”

Maddy Sukhdeo, who graduated in May with degrees in Writing Seminars and psychology, spent the majority of her first year on the university’s Homewood campus before the pandemic forced most students home in March 2020. When she returned to campus the following spring, she noticed a distinct difference.

“It was kind of like, Whoa, there is all this diversity that I originally thought wasn’t here,” said Sukhdeo, whose mother is white and father is Black. “You walk around and there are people of all different backgrounds, which is not something I had experienced in my freshman fall.”

As a result, Hopkins students are exposed to peers with different viewpoints and ideas and experiences from the moment they set foot on campus during their first semester, said Omobolade Odedoyin, who graduated in May with a degree in applied mathematics and statistics.

“I think being encouraged to discuss things with people who don’t necessarily have the same background as you definitely helps widen your perspective on a lot of things,” said Odedoyin, who was raised in East Baltimore and whose parents emigrated from Nigeria to the U.S. in the 1990s. “You become more informed by just being around different people.”

Image credit: Pam Li / Johns Hopkins University

Diversity can mean a lot of things. Some you can see, as Sukhdeo and Hussain did. Some are not as visible, like diversity in socioeconomic backgrounds. But that has increased as well.

Talented students like Azmi are part of the university’s FLI—first-generation and/or limited-income—community, which has increased from 20% in 2017 to close to 30% now.

Limited-income students, measured as those who qualify for federal Pell grants, made up less than 10% of the student body when Daniels arrived. Phillips said 20% is an informal standard commonly accepted among universities. In the past four years, Hopkins has exceeded 20%.

Removing barriers

With the Bloomberg Philanthropies gift providing the financial resources, Hopkins has implemented several changes in admissions and financial aid policies. All have significantly affected the pool of qualified applicants and ultimately the makeup of the student body.

Need-blind admissions

Fulfilling a commitment he made at his installation in 2009, Daniels announced in 2018 that the university would be permanently need-blind in its admission policy for domestic students. That means Hopkins will not consider an applicant’s financial situation when deciding on admission.

This can lead to a mindset change among potential applicants. Some had a perception that their finances reduced (or eliminated) their chances of being accepted, and so would opt to not apply. Without that concern, more high-quality, limited-income candidates are applying. If they are admitted, Johns Hopkins can meet their needs with financial aid packages.

“It’s a promise we make that if you are deserving of a place at Hopkins based on your background and academics, we will support you and figure out a way to make the finances work,” said Tom McDermott, associate vice provost for financial aid. McDermott noted that while need-blind admission currently only applies only to domestic students, the university is exploring expanding it to international students.

Loan-free financial aid

Another immediate change was to eliminate loans from university financial aid. Previously, packages included grants along with the expectation that students would take on loans. Now the aid is all grants and scholarships, plus a work-study program. “It’s a much more supportive financial aid package we’re able to provide today, giving students the freedom and flexibility to pursue their college and post-college plans,” Phillips said.

The average grant award for first-year students in the 2023-24 academic year was $60,000, which covers 70% of the cost to attend. That’s up from $44,886 in 2018, which covered 58% of the cost to attend. Across the full undergraduate population, the university spends $161 million annually on need-based grants. At the same time, the number of students who are taking out loans has decreased.

“It really levels the playing field,” McDermott said. “Essentially we’re telling students and their families that if they warrant admission to Johns Hopkins, finances should not be a barrier to them attending.”

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

The financial aid package arrives alongside the acceptance letter, McDermott said, so prospective students can have the full financial picture when deciding whether to attend.

Added Phillips: “We have a simple message: We will meet your full demonstrated need with a financial aid package tailored to your family’s circumstances. When potential applicants realize their unique situation may mean they only pay a fraction of the sticker price, and with the added benefit of graduating without student loan debt, they start to realize, ‘Maybe this is possible for me.'”

That was the experience for Melody Lei, who graduated this past spring with a degree in mechanical engineering.

“It was the deciding factor for me, just seeing the financial aid,” said Lei, who is considered a FLI student. Lei said even with aid and scholarships, other schools she was considering—private and public—would have cost $15,000 to $30,000 more per year out-of-pocket. “It eliminated all my other options,” she said.

Azmi narrowed her choices down to two schools. With her aid package, her first-year cost at Hopkins was half of what it would have been at the other option. “You can’t turn that down,” she said.

Elimination of legacy admissions

This was something Daniels tested out beginning in 2014 and made official in 2019. It means that the alumni status of an applicant’s family members cannot factor into whether that student is admitted. For Daniels, this was a move toward increased opportunities and admissions based on merit, not family history.

In 2009, the incoming class had more students with legacy status than it had students who qualified for Pell grants. In the most recent entering classes, less than 2% have legacy status.

Commitment to limited-income students

When Bloomberg’s gift was announced, Daniels committed to a student body in which at least 20% of students were eligible for Pell grants by 2023. That goal has already been exceeded, ahead of schedule.

With many barriers removed, Hopkins modified its recruiting approach to attract more diverse high-achieving applicants. That included an increased focus on high schools in underresourced communities, including Title 1 schools—those that receive funding from a federal program designed to support students from low-income households—and partnering with community-based organizations that typically work with successful students who are first-generation, limited-income, or come from underrepresented groups.

Plus, there’s the natural cycle of progress leading to more progress. More diverse undergraduates lead to a more diverse alumni base advocating for the university. Underclassmen in high school may see others from their school going to Hopkins and consider it for themselves. Prospective students visiting campus may have a tour guide that looks more like them or comes from a similar background.

Sukhdeo, an intern in the Office of Multicultural Affairs, remembers speaking to prospective students of color as part of a panel discussion. “I could tell these students that, yes, there is a space for you on campus, and the university has made a commitment to creating that,” she said.

After a visit to campus the spring of her senior year of high school, Azmi knew she made the right choice.

“I remember looking at the statistics for diversity here,” she said. “Then I was able to come visit for the spring open house, and there was a resource fair, and each table I visited said they were here to support you. I didn’t see that elsewhere.”

Added Phillips: “Ten years ago, if you were a student from a limited-income background or you were from an underrepresented racial group and you came to visit Hopkins, you probably said, ‘I don’t see students like myself here. Is this really a place for me?’ We’ve done a lot to make it feel like it’s a place for everybody.”

Credit: Source link