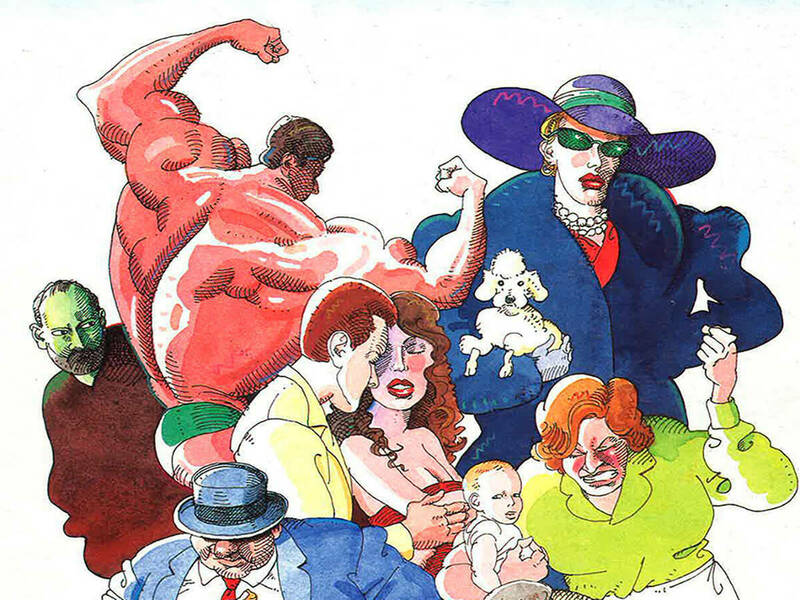

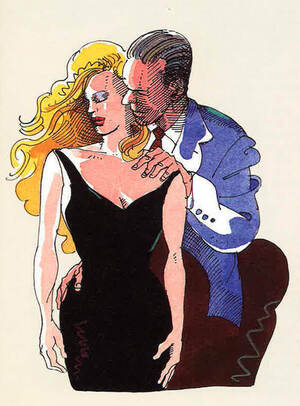

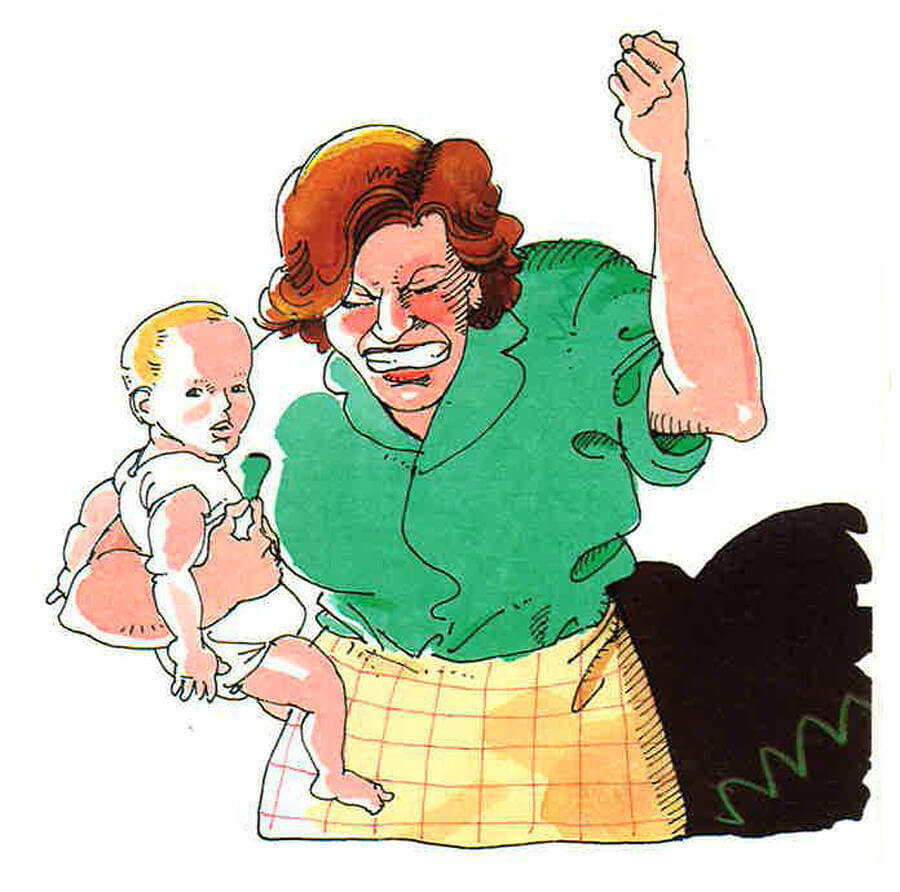

Illustrations by Joe Ciardiello

Editor’s Note: On a peaceful Saturday morning in early September I sat in my backyard, savoring the scene before me: the grass and trees and black-eyed Susans, all feeling different now — as the sunlight and scents took on an autumn mood. It reminded me of a memorable essay from years back, and that got me to conjuring a list of all-time personal favorites published in the magazine over the years. I decided to share them with you, a new one each Saturday until the calendar reaches 2024. I had wanted the magazine to do a story about the Seven Deadly Sins for a long while, but couldn’t find the right writer for such a project. Along came Brooke Hearn, a high school teacher who had randomly sent us an unsolicited essay. She seemed to be up to the task and so I pitched the idea to her. What follows is her masterful evaluation of the sins and American culture. My advice: Read one at a time. Each one is a gem of depth and brilliance.

To name the Seven Deadly Sins is to invoke echoes of Puritanical thunder and ghostly smoke from the pyres of the Spanish Inquisition. The Sins walked the stages of medieval morality plays, fantastic characters quaintly childlike to modern minds and remotely picturesque, like gargoyles, flowing robes and halos — all signs of a culture that viewed sins as henchmen of Evil, bent on a diabolical mission to divert humans from the narrow path of salvation.

In one of the livelier scenes from a 15th-century play, the Seven Sins besiege Mankind, generic humanity, in the Castle of Perseverance until the Virtues within the Castle win the day by pelting them with roses that signify the Passion of Christ. The Sins return to lead the poor, dimwitted hero off course again, but there’s a happy ending. Gentle Mercy and Peace drown out the demands of stern Righteousness for just retribution and persuade God to welcome penitent Mankind into His presence for an eternity of bliss. So ends the drama of every Christian soul that throws itself upon the Church’s mercies, according to the wisdom of the time. The answer to life’s thorniest question — how are we supposed to live here? — was simple for the faithful.

The authors of morality plays, however, were less simple than the message they delivered. The mind of medieval Europe danced nimbly among complexities and made its home in paradoxes every bit as weird as the theories of modern physics. Theologians in charge of Western Man’s spiritual and mental development — as well as much of his real estate — saw him as a contradictory blend of angel and beast, the very heart of God’s mysterious Creation. Without suspecting that their heavy oaken chairs and tables were actually composed of space and moving particles, believers knew things weren’t just what they seemed. If a rose was a rose, it was also a sign of Something Else. To them, the World was not only its gigantic and diversely solid self, our material frame, but also an illusory veil of snares employed by Satan to entrap a naive spirit, which could escape into the clear and certain air of Heaven only through the intervention of the Church.

While each rock and creature had its place in a Divine scheme, at the same time all the matter was ephemeral and unimportant. Man’s spirit, alone in the earthly Creation, partook of the eternal. The drama of human souls wrested from God by sin and returned to Him by the Church was the central story, the heart of the cosmic mystery, the only show in town for Western Europe.

These days, riding our tiny planet around a middle-sized galaxy through a universe that doesn’t seem to have a center anywhere, we find it harder to believe that we human beings and our fate are the point of it all. Our perspective has flipped. While Earth’s uncharted territories shrink and astronauts’ photographs fill us with tenderness for this blue and lovely glob — while Armageddon lies leashed in our labs and we understand that we ourselves may be the authors of Judgment Day — our telescopes probe ever farther into space without disclosing any welcoming gates, and a geographical Heaven recedes into shadowy improbability.

What’s more, mankind’s increasing dominion over the earth has made many of us too comfortable to care about any life hereafter, content just to joyride in the present. Woody Allen sums up the average person’s metaphysical scope when he asks about the unseen world, “How far is it from midtown, and how late is it open?”

In this enlightened century, priests don’t burn heretics for the public good; instead, modern arbiters of virtue grill them in front of cameras. Lawyers, not angels, argue over the fates of mavericks, while social workers search out environmental causes for aberrant behavior. We trust science and money to solve most problems. No one talks much about Evil, except for an occasional psychiatrist.

We are growing up, taking the reins of our own lives away from an elect priesthood, only to find existential paradox more baffling than ever. The pursuit of happiness here in Technology Land evolves into the pursuit of loneliness as do-it-yourselfers end their days in the old-age homes. Psychotherapy hasn’t been able to put joy into the search for fun. In our effort to secure material bliss and be sure nothing BAD ever happens to us, we are sapped by proliferating things — and the insurance on them.

Fortunate people seem tired and uneasy, minds hardened and old in bodies kept supple by expensive exercise. Lightness and balance are as elusive as ever, within the churches and without. The clarity of spiritual calm, that internal truth mirrored in the idea of an external Heaven, is glimpsed now and then only in the few who manage miraculously to sidestep those old ministers of heaviness, the Seven Deadly Sins.

They are still lively and persuasive in the 20th century. Let’s call them by their old names.

LUST

A FISSURE AT THE HEART OF FEELING

“Lust” meant pleasure to its Old-English originators. Well into the 17th century, the word was used to convey delight, appetite or inclination for something. Anything.

Typically suspicious of pleasures of the flesh, Christian theologians attached the word to the appetite most troublesome to them, and in the context of a religion uncomfortable with sexuality, “lust” came to mean libidinous desire or degrading animal passion.

Though one may still occasionally lust after a boat or a painting or a place to live, the original meaning has nearly vanished. We view sexual yearning in a different moral light than a hankering for clam chowder. Sex was always more explosive than soup, I suspect, but out remote forebears seemed to take a more inclusive view of normal desires than we do.

Victorian England sent lust underground for 100 years in the English-speaking countries, camouflaging desire with decorum, banning the body from sight and from conversation. Shakespeare’s direct, earthly language was mildewed over with euphemism as an inflammatory term like “leg” became “limb” in polite discourse. Stories abound of carefully raised young men like John Ruskin paralyzed at the sight of their naked new wives, and of women marrying without the slightest notion about sex, unaware months later that their marriages were unconsummated.

A fissure at the very heart of feeling was the result. Underneath the verbal delicacy and the voluminous skirts, Eros proceeded as usual. Victorian families were enormous (Charles Dickens fathered 10 children before divorcing the wife who bore them and bored him) and the infidelities prodigious. Yet conventions that separated life from language, nature from respectability, hardened a distinction in the mind between lust and love in the country whose culture most deeply influenced our own. Lust sent young men to prostitutes, the inferior women to whom they could appropriately express their desire. Love decreed chaste reverence among young men for Wives and Mothers — women above sexuality who, once married, suffered physical intimacy dutifully in the spirit of the often-quoted maternal advice: “Close your eyes and think of England.”

It would be hard to say which group suffered most. When desire was not legitimately reciprocal, it became furtive and flirted with disease. Even before Victoria’s time, the poet William Blake mourned over the devastating schisms in the soul and the social fabric inflicted by fear of human nature: “But curse/Blasts the newborn Infant’s tear,/And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.”

On this side of the Atlantic, Nathaniel Hawthorne recognized the tragic loss of beauty in life when society’s law thwarts nature’s, but he couldn’t rescue his Hester Prynne from Puritan condemnation or even conceive, from his 19th-century perch, of a society in which men and women lived justly and fully together. Since sexual passion was shameful, men felt divided within themselves and women were victimized, objectified. The division plagues us still, even after Freud, the advent of birth control and the moral explosion of the ’60s.

Everyone over 35 remembers the posters (“The Body is Beautiful”), the bumper stickers (“Make Love Not War”) and the love-ins danced to a beat more grossly and merrily suggestive than anything since Chaucer. Lust came out of the closet and slammed the door behind it. Caution and cashmere were jettisoned together as kids with choices bought used jeans or put on army surplus, gathered in democratic communes and, ignoring all the cows sacred to their coupon-clipping parents, tried to explore the beauties of the earth and their bodies, living freely in the moment without counting costs.

Somehow, though, the movement that meant to make life honest — the “Greening of America” — was blighted as the media translated it into the business of living: Sex means sales. And what are the persuaders? Hints of sado-masochism in the poses of glowering, semi-nude Vogue magazine models; in advertising, a meatmarket approach to the body, usually the female but lately the male as well; sex on the screens, large and small, coupled with violence — as though the liberation of lust had been a bloody revolution, dragging a sad aftermath of anger.

Lust is still divorced from liking — or any responsible concern for another person — and it looks ugly. Perhaps we don’t like ourselves enough to trust the yearnings for such intimate exploration of another as our bodies desire. Perhaps we don’t believe ourselves capable of the spiritual fire that is potential in the strongest physical passion. In a book he describes as a “personal adventure into the sources of our life and legend,” Alexander Eliot wrote: “It was a dark day when the church fathers decided to make demons of the pagan gods. What followed was a slow, forced separation of Christian thought from nature — and from natural passions. . . . People who mistake sex for a thing of sordid pleasure, guilt and shame are farthest away from the goddess. Foam-born Aphrodite can’t be bought, not for love or money. Nor is she ever — in herself — a cause for regret. She comes as a gift and goes again, like a fair wind off the sea.”

British novelist E. M. Forster urged that we “only connect.” Put things together. It may be there’s no holiness for us without wholeness, the acceptance and integration of our natures. It may be that sexual desire, whatever its beginnings in the desire for union with our mothers and whatever its inconvenience, is one of the few avenues open to limited understandings, one of the ways in which we touch the mysterious dimensions in which we live.

We sin in criminalizing the difficult. More intuitive about themselves than we are, the ancient Greeks were able to laugh at the sexual predicaments of their gods and heroes. Heracles — with all of his lusty appetites — attained Olympus through a generous nature and heroic service and was welcomed into godhood. These days, the American press wouldn’t let him win a seat in the Senate.

Terrified by our inner mysteries even after a half century of psychoanalysis, we remain pious, prim and partial. The politicians who survive scrutiny will reflect those values — this in a time that calls for heroic imagination.

To separate humans from their own nature is to separate them from all nature. In the divorce of desire from love and decency we may find the roots of our insensitivity to this planet. That which we don’t know how to love bravely, we use cruelly. Loathing ourselves, we violate one another and rape the earth.

AVARICE

THE GORGEOUS ILLUSION OF WEALTH’S POETRY

Avarice doesn’t seem unreasonable, now that physicists are explaining things. It’s a perfectly legitimate confusion traceable to the nature of the universe. Consider: We are told on the best authority that all observable reality — all of it, from soap bubbles to Mount Rushmore, mountain bikes, Manhattan Island, Classic Coke, the Supreme Court, red squirrels, black bears, junk bonds, your mom’s Apple computer, Neptune’s moons, Woody Allen’s movies — is composed of subatomic particles that are not clearly either matter or energy (those two distinct, we thought, elements of creation).

Who can blame us for snatching at matter to fill gaps of the spirit when no one knows where one ends and the other begins? Now at least we can see why, decades before anyone talked publicly about quarks or other spooky ideas that scientists accept on faith, jazz-age novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald was beguiled with the beauty of lives couched in money.

The romance of wealth isn’t a peculiarly American phenomenon — witness the Midas legend and the Medici family — but it has grown in our free-wheeling climate, without the inhibiting baggage of tradition and cultural unity, into a full-fledged myth, impervious to the bashings of experience. Fitzgerald said, “The rich are different.” Like him, most Americans think that wealth has sorcery — not just buying power and ease, but transforming magic. The more news stories we read about the pitfalls and miseries of affluence, the more we all want to try it ourselves.

If the saga of Jim and Tammy Bakker lacks the glamour and poignancy of The Great Gatsby, the two stories are nonetheless cousins. Maybe a great novelist could convince us that solid gold bathtub faucets and $1,600-per-day hotel suites beckoned the Bakkers toward the same shimmering promise of transcendent loveliness that Gatsby saw in the green light on Daisy Buchanan’s remote dock. Daisy and her world may be a cheap show and Gatsby crude, bootlegging his way to Daisy’s notice, but we don’t laugh at him. We sympathize, so powerfully evoked is the longing Gatsby (and Fitzgerald) felt for that spacious, light and youthful pattern, the gorgeous illusion of wealth’s poetry.

Money as beauty is hard to resist. So is the lure of philanthropy, money as capacity to change the world. It is probably easy to justify tromping on a few miserable corporations, putting a couple hundred airline or steel workers out of work with a takeover, when your new personal fortune is going to fund a center for the aged, a museum to glorify Native American art, or even a ship to bring medicine to people beyond the third world — all named after you. That is power and glory.

Compulsive ownership is harder to understand. Why a mania for things? How is it that a man who drives seven miles to get an office and a home again each day wants five cars in his garage, all equipped with finicky transmissions, fragile exhaust systems and delicate, computerized sound systems? Why does a woman whose house is an impenetrable maze of furniture hunt down antiques — her eyes agleam with acquisitive passion — and keep cramming them in?

Why would Donald Trump tie up $38 million in his yacht, saddling himself with a 282-foot maintenance nightmare, when the same money could fund reading programs in three inner cities and attack crime in its cradle? Is it that things give us the illusion of control over the uncontrollable? As time rushes us down river, do we grab at the reeds along the banks to slow our inevitable progress toward the mystery of open water?

Death makes life tough for everybody. Shakespeare agonized over it and declared he would last somehow: “Not marble, nor the gilded monuments/Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme,” he said, and so far at least part of him has survived because he faced all of life and death squarely, giving the spirit what it cried for. Elizabethan England believed in the power of words to penetrate and prevail.

Power in the 1990s looks different. Watching videos on a 27-inch screen from the 15-foot bed in his private quarters on the Trump Princess while a crew of 35 met his needs, Trump could avoid confronting life. He could escape knowing that the water he plowed is polluted and the streets of the port city were unsafe for him. Inside his dark, protective windows, time itself may have seemed to stand still. Also, people noticed his yacht’s arrival, but that’s another subject.

It is easy for most of us — trying to keep the antiquated washing machine running till the tuition bills are paid — to feel a pious queasiness at bizarre material excesses, but harder to know at what level greed begins or whether we would be any freer and wiser in the shoes of the rich. We may be sickened by the image of a beaming Malcolm Forbes and a plump, bejeweled Liz Taylor cutting the cake at his $2 million birthday party, but is my gobbling up sweaters on sale part of the same revolting business? Would specters of the homeless and the groaning ecological balance lose their power to haunt me if I had a few billion of my own?

Money is a habit-forming drug. At dinner recently, I asked some friends what they would do if they suddenly had $100 million to spend. Their reactions were varied: “Round up the drug dealers and drop them by parachute on Tehran” . . . a few wistful endowments for schools and programs. Two people stopped just short of crossing themselves and said they’d get rid of the money fast, dump it on a foundation. Cowards or realists? In their experience of the world, great wealth blurs human intention and obscures reality for everyone. Like the man-eating plant in Little Shop of Horrors, greed is insatiable.

It is nearly two centuries since Wordsworth complained to the English, “Late and soon/Getting and spending, we lay waste to our powers.” Nothing has changed, nor are those powers defined any more clearly for us than they were for him. What are we supposed to be doing with our immense vitality if not hoarding endless varieties of nuts against a winter that may have no spring?

Even the church has had trouble with the question. Paradoxically resplendent and powerful as it extols the life of a modest carpenter, it delivers a mixed message. When Jesus said “the poor are always with us,” did he mean that there’s no use in trying to alleviate poverty? Was he sanctioning episcopal treasure as an earthly paradigm of heavenly glory? Or did he mean that the poor have the same spiritual opportunities as the non-poor, so riches are irrelevant?

One thing seems clear: If his life was meant to show us the Way, then gilded crosses are no less a detour than gilded faucets. I wonder, when people are drawn into the glorious cathedrals by pomp and pageantry, whether they ever learn there the language of the spirit. Or do they keep reading the lesson always in front of them: “Go for the gold.”

Riches are not the only comforts we clutch greedily to us. Men rack up sexual conquests and brag about them. So do women. Husbands and wives suffocate each other with constant demands for service or attention. Friends demand impossible, exclusive loyalties. Human parents hover possessively over 30-year-old offspring with intrusive advice. Have you ever seen a bird follow its fledglings to the new nesting ground yelling, “Hey don’t build it that way . . . ”? The fear that we won’t exist enough if we let go of anything is strictly human, a paranoid aberration from natural wisdom.

Wordsworth thought we could find our way out of our materialistic treadmill and recover that wisdom by somehow reweaving ancient ties to the natural world. For him, an awareness that was discredited and forgotten in the cerebral Age of Reason was the route into our own deepest natures, all possible earthly happiness, the sense of God. He tramped miles over land he didn’t own, writing of nature’s moments — daffodils, clouds, rainbows and sunsets — with a passionate sense of personal connection that made the territory his own in a way no fence or “Keep Out” sign could have done.

If we can take time out from SAT practice, law school, corporate demands and board meetings—at some point before we drop dead — a little contemplation may bring us down to earth. It may show us that on this ebbing, flowing, coming and going that we call a planet, possession is the cloudiest proposition of all.

Meanwhile, could someone tell me: What on God’s green earth is a junk bond?

GLUTTONY

WHERE HAVE THE MEALTIMES GONE?

A friend of mine trying to shed some midsection puffiness has adopted a regime he can boil down into a simple maxim: “If it tastes good, spit it out.” He will suffer through countless salt-free pretzels and cans of dry tuna — mainly resisting the chocolate eclairs and sticky buns beckoning from the bakery windows — and redefine his waist. For awhile.

No one would call him a glutton. He is a life-loving guy with a sweet tooth who needs more exercise than he can schedule. Chocolate doughnuts or napoleons may tempt him three times a day at mealtimes, but for 15, say, of his 17 waking hours, he can relax his vigilance.

Not so the mountainous sacks of flesh photographed in hospital beds, limbs almost too swollen to move, jaws wired to keep them from eating — or the bulemic adolescents who gorge and regurgitate till they are unable to retain anything and so starve to death, enslaved by the food they reject. In our land of plenty, even the poverty-stricken hungry are probably less obsessed with food than the neurotics who eat to assuage misery or act out of self-loathing. The rise of eating disorders in America makes gluttony a national problem.

Given a propensity for some kind of addiction, what is a man or woman more likely to turn to than food? It is our first comfort; our mothers’ milk brings with it the most perfect warmth and nurture we may ever know. Later, other foods — hot soup on a cold watch, the fragrance of cooking apples meeting the traveler, a hearty stew and wine with conversation — punctuate hard lives with cheer.

Long after the family gathering in a grandparents’ house is forgotten, the smell of blueberry pies baking or spiced gooseberries can bring it back, with all its sprawl of cousins on sofas, its china and glassware, its particular jokes. Look at the four ponderous volumes of intricate memories Proust claimed to retrieve with just one taste of a childhood sweet. It is an atavistic hangover, no doubt but the taste and smell of food stay with us longer, fresh in their associations, than any other sensory harvest.

We send food as presents: fruit from Florida and Oregon, hams from Virginia, cheese from Wisconsin — if you’re lucky, caviar from Russia. Food is the cornerstone of hospitality and has been since Odysseus’ time — if the guest is not fed, the host is shamed. The unpredictable guest was disarmed by food. So were the gods, and food was the obvious propitiatory sacrifice. In a mystical transformation of food’s nurture of mind and body, Christ comes to Christians as bread and wine, to be eaten.

The poetic or magical sense of eating as a way of transferring power is ancient. By accepting a miserable six pomegranate seeds in his realm, Proserpine enabled Hades to keep her in the Underworld for six months each year. Figures in Chinese legend triumphed by eating.

Maxine Hong Kingston writes in The Woman Warrior, “All heroes are bold toward food” and tells of the scholar who swallowed dozens — then hundreds — of frogs spewing from a treasure he found till the frog spirit was drained of mischief and left him the silver ingots for himself. “Big eaters win,” she says. The hero defeats the enemy by incorporating it into himself, not by resisting. His great, lusty “YES!” exhausts the evil.

Immigrants who fled poverty abroad and came to America for opportunity also believed that big eaters won. For those too practiced in hunger to believe in prosperity, extra fat was money in the bank, stored against the lurking bad year. Obsession lingered amidst plenty like a scar. That sort of hoarding was different from the oral fixation that plagues comfortable Americans, the need to be constantly sucking or chewing on something that delivers a quick, fickle, sugar fix, a caffeine or nicotine high, a taste of salt or sweet. The junk-food industry panders to an infantile compulsion with no remaining ties to its original purpose, nutrition, so that meals seem to have disappeared from our culture. Few families gather around a table two or three times a day anymore; instead, airports and malls are crowded with people rushing along and chomping away on cellophane-wrapped goodies with all the food value of paper towels. The result — perpetual hunger and the need for more chocolate chips or Twinkies.

At the same time, everyone insists on a body shape possible only to those with ascetic discipline or the metabolism of a sparrow. Hence our guilt, and the increased compulsion to eat for comfort.

The ancient awareness of magic in food and eating — of health in herbs and strength in assimilation of the terrifying — has become a pale travesty of itself in the furtive, “I’ll eat this to make myself feel better for a minute.” The soul-feeding chatter around a candlelit table and the ritual mystiques of beloved recipes have given way to quick energy fixes and oral gratifications snatched in lieu of happiness.

Concerned health experts warn us we are what we eat. I wonder if Nikos Kazantzakis’ irrepressible Zorba the Greek isn’t closer to the truth when he says, “Tell me what you do with the food you eat, and I’ll tell you who you are. Some turn their food into fat and manure, some into work and good humor, and others, I’m told, into God. So there must be three sorts of men.”

My friend of the doughnut wistfulness falls gracefully somewhere between the last two sorts, a lucky and unusual man. Finding God amid the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to — not to mention the unnatural ones this century has come up with — is a tall order, but maybe it always was and maybe the search is enough to put our lives in balance. To judge by the expressions on the faces of commuters any Wednesday morning, good humor is even more elusive than God; we see someone smiling in his car and ask, “What does that guy know?” Something. Enough, the chances are, to have kept the body and spirit of things together somehow.

All the sins of excess — Lust, Avarice, and Gluttony — seem to emerge when we lose that balance. We get sick when the object or vehicle of desire is divorced from the mind or spirit of desire — namely, the delight and the will that seem to make it all happen here: the small feasts, the great loves and, probably, the motion of the stars.

WRATH

THE UGLY TWIN

Long before men conceived of sin — in the Eden that was perhaps our species’ unselfconscious infancy among the other animals — wrath and fear kept us alive. A prehistoric Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes might have prayed, “Give me the strength to kill the enemies I can, the speed to flee the ones I can’t, and the sense to know the difference.” A charge of adrenalin provided — then as now — the motivating anger or terror, but not the wisdom. Hence, the survival of the realist in a brutal world dominated by physical strength.

In spite of the jungle shadows cast by our gruesome headlines, not many of us in the 20th-century United States carry or fear weapons as we forage for groceries because our battleground has increasingly become an internal one. Most often it is our sense of self that’s threatened, not our lives. Still, the adrenalin pumps — the human animal reacts to the delicious power-surge of anger now with sarcasm or accusation, or to the clammy grip of fear by withdrawing — but winners are hard to distinguish from losers. Even among the clever, survival may be a matter of opinion, and the psyche we shred is often our own.

Self-awareness complicated our relatively simple game of If-I’m-Strong-Enough-to-Keep-It-It’s-Mine. Now there are sand traps, tricky concepts like guilt and sin, and we don’t just club competitors over the head and eat our warthog chops in peace any more. Instead, percussions and repercussions reverberate down the years, generation after generation, and haunt us with spectral battles not our own. A battered child becomes a brutal father who engenders a rapacious CEO. Anger has become so obviously perilous, not only to the recipient but to the one who feels it, that theologians separated it with the other sins of the spirit: Envy, Pride, and Sloth. The question is: Have we outlawed the wrong twin?

A look around an American city explains why wrath continues to take the rap: It’s ugly. Rage boils under the thin surface of modern lives, erupting in jagged crawls on city fences, in the passive-aggressive delay tactics of postal officials, or in the obscene gestures of drivers as they jam accelerators to the floor and graze cyclists. Civility is a lost art on both the public and domestic fronts (we call them “fronts” as though they were war zones), and insult breeds outrage. We respond to the snarls of our politicians and husbands or wives with defiance that is angrier because it covers secret guilt, a hangover from the magical, egocentric thinking of childhood.

When we were small, a door that slammed on our fingers did so intentionally, a thunderstorm was directed at us alone, a parent’s rage at the world was our fault. No wonder Jonathon Edwards could chill the blood of his 18th-century congregation with “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The sermon paralyzed parishioners not because a ferocious God was a shock but because he wasn’t. They recognized the model, a Being who responds to our absentminded or unwitting lapses with the baffling violence of earthly fathers. Even as adults we feel secretly responsible for and targeted by the tantrums of others, so we internalize them and pass them along, raging at all the delays and demands that prevent our perfection by wasting our precious time.

Time drives our 20th-century lives. As we roll into the millennium with our options multiplying, the pace is picking up but the human metabolisms lag behind. Few men or women are as Type A as they manage to appear after three cups of coffee and a workout on a Nautilus. My summer days of island living tell me I’m temperamentally back in the 12th century. Then, Time lazed along through days monotonously indistinguishable till frost or new leaves on the willow woke everyone up to — Hey! A new season!

The medieval division of the day into hours for prayers probably seemed finicky to feudal households. Yet here we are, a few measly hundred years later, scrambling before these inexorable minutes and seconds doled out by digital watches that fix us in one single moment — no sweep of past or future but only the isolated present instant, which is there . . . and gone . . . as we opt for all the possible choices simultaneously.

Women feel pressed to be mothers, chauffeurs, housekeepers, Cordon Bleu cooks and nurses in their spare time now, while they run corporations or galleries. Men sold on the idea of sharing take their turns at the diapers and cooking while trying to maintain competitive law practices 12 hours each day and be good listeners in the evening. To a modern child, rushed from lesson to lesson or babysat by hardsell TV, Huck Finn’s leisurely float down the Mississippi is alien and boring, as incomprehensible and lonely as a moonscape.

In all of us, near-panic is the norm. “How ya doin’?” we ask. “Making it!” is a positive reply. A wet sparkplug or a child’s books forgotten at school can trigger a parental stroke. People drop dead racing to stress tests.

Gridlocked on my way to the airport, I pry my clenched hand off the wheel, close my eyes and concentrate on a mental picture. A smiling, bead-hung Polynesian, who runs his own business, is living differently and longer on his Pacific island. His response to snarled traffic is: “When that truck move, I go.” He is sane and succinctly Holmesian. He changes what he can, accepts serenely what he can’t, and is wise enough to know the difference. His simple, transcendent sense of proportion could free me from terminal self-importance and the tyranny of my relentless watch. Maybe. If I’m not too terrified.

We are afraid to miss a plane — in missing it we might miss something else or incur displeasure. We might be viewed as flawed. We might even be flawed. One of Kurt Vonnegut’s characters proposes that detours and other hitches in a smooth life are dancing lessons from God, but most of us are as unable to get off the highway and dance as we are to be honest, to be comfortably alone, or to love our imperfect neighbors. If we were braver, less appalled by the void out there and the one within, then Patience, Wrath’s virtuous counterpart, might stand a better chance with us.

A wise counselor told me once that anger covers pain. “Take your sadness to breakfast,” she said, meaning “have the courage to face it; give it time and attention.” Otherwise, legitimate, self-preserving anger at true enemies (usually unacceptable and therefore repressed) surfaces in headaches and back spasms (acceptable) or in cowardly attacks on the helpless (unpunishable), and we are crippled by it. The rage of a worker who goes home to wreak havoc instead of confronting the boss remains unexpressed; it distorts and confuses his world and ours.

The anger that rises and erupts in some of the most powerful novels and plays in the last 50 years is different. In women suddenly aware that adventurous females can be described only in male terms (like “tomboy”), in South Africans, in Black or Chinese Americans, rage at dispossession becomes a creative force, opening and changing minds. That anger clarifies. It blows like a northwest breeze through stuffy boardrooms and petrified curricula, bringing new voices, new idioms and shapes, the vigor of truth.

E.M. Forster and Virginia Woolf, Kate Chopin, Alan Paton and Nadine Gordimer, August Wilson, Toni Morrison, Maxine Hong Kingston — all the brave people who have allowed the pain of existence to form and inform them — teach us that it is not wrath that warps our lives, but fear. In this less serious but still brutal world we have inherited, we need more realists, hopeful enough to reject trivial pursuits, courageous enough to embrace their anger and put it to work for us all.

PRIDE

THE SELF-DESTRUCT BUTTON

“Pride goeth before destruction/And a haughty spirit before a fall,” said Alexander Pope magisterially after looking history over. And he wasn’t the first to notice.

Is anyone listening out there? A couple of millennia might seem like a reasonable no-gain period if measured against geological time, but in terms of human history it seems longish. Though warnings have abounded, we continue to skirt the edges of obliteration with the 16-year-old driver’s confidence that it can’t happen to us.

Greek heroes were creamed for their hubris by angry gods, Hitler fell, Iranscam followed Watergate, Washington’s mayor imagines that laws are for underlings — all to an ever-renewed public horror, as though no one had ever told us about the blinding corruption of power, the dangers of pride.

We keep paraphrasing ourselves as the centuries roll along. In 1982, after serving as aide to Lyndon Johnson, Jack Valenti told a writer for The New York Times: “You sit next to the Sun King, and you bask in his rays, and you have those three magic words, ‘the President wants.’ And all of a sudden you have power unimagined by you before you sat in that job. And if you don’t watch out, you begin to believe that it is your splendid intellect, your charm and your insights into the human condition that give you all this power. . . . And even people who would like to discipline themselves are caught off guard. The arrogance sinks deeper into their veins than they think possible. I’m telling you, this is like mainlining heroin. And while you are exercising it, it is so blinding and dazzling that you forget, literally forget, that it is borrowed and transitory power.”

Eleven centuries ago during the dark ages, an Anglo-Saxon poet who wove legends about the feats of long dead kings put these words in the mouth of Hrothgar, a 5th-century Dane: “Be warned, Beowulf, learn the nature of nobility. I who tell you this story am many winters old. It is a miracle how the almighty Lord in his generosity gives wisdom and land and high estate to people on earth; all things are in his power. At times he allows a noble man’s mind to experience happiness, grants he should rule over a pleasant, prosperous country, a stronghold of men, makes subject to him regions of earth, a wide kingdom, until in his stupidity there is no end to his ambition. . . . He suffers no setbacks until the seed of arrogance is sown and grows within him, while still the watchman slumbers; how deeply the soul’s guardian sleeps when a man is enmeshed in matters of this world; the evil archer stands close with his drawn bow, his bristling quiver. Then the poisoned shaft pierces his mind under his helmet and he does not know how to resist the devil’s insidious, secret temptations.”

In the centuries between these two versions of the same message, history dealt us an illustrative procession of egomaniacs and plenty of Hobbesian-Machiavellian advice on the uses of power, but my bet is that Valenti did not concern himself deeply with the lives of the dead dictators or remember Beowulf from college English. He came to Hrothgar’s point of view only through direct experience of men who define themselves by their control of events and other men.

The checks and balances in our government seem to frustrate lawmakers without noticeably impeding excess. Perhaps if we gave modesty a chance, if we put “Hail to the Chief” in mothballs and sent our officials out in public guarded by men dressed like janitors, we could expect more realistic perspective in high places.

I was present inadvertently when former President Ronald Reagan arrived on Tilghman Island, Maryland, several summers ago to address the watermen and sign a bill providing token aid for the Chesapeake Bay clean-up. The drawbridge was raised at 9 a.m., freezing traffic on and off the island; state police and Secret Service men in dark blue suits with gold lapel insignia swarmed over the one pothole-pocked road and the small docks, banning private boat launchings till 2 p.m. Thirty or so watermen lined up webbed aluminum chairs along the edges of their lawns to watch — in contemptuous violation of the Secret Service interdict against leaving their porches. They sat resolutely with their families, taking in the approach of four giant helicopters. One — the president’s — landed while the other three circled noisily.

What does it cost to keep three helicopters circling for two hours while the president is photographed talking to several watermen? What might the money have done for the cleanup effort? All this niggling economy aside, what does it cost a man in perspective to be accorded such importance? If we don’t want to be cut off in the flower of our arrested development, we need to stop behaving as though we were all new here, politically, and learn the difference between a movie star and a statesman.

Closer to home for most human beings is the question of our own roles. Being at the top of the food chain does not necessarily mean being top-of-the-mark qualitatively. As the world shrinks and warms, suspicion arises in gloomy bosoms that human intelligence is an evolutionary blind alley, that we are a collective Icarus, flying too high not to melt our wings and perish. Porpoises may not only be prettier and more fun; they may also be able to teach us something we need to know. We need to unload our medieval baggage, the concept of humankind as the pinnacle of creation and God’s treasure, of Earth as a mere framework for human history.

Once, in a time when natural resources were more plentiful than people and were usually terrifying, it was possible to think in terms of subjugation and extol our heroes for winning over their environment and its monsters . . . but today? We and our poisons have become the monsters.

Native Americans still conceive of the earth with all its inhabitants as an organism, a related, living whole like the ancient Greeks’ Mother Gaia. One trip down into the Grand Canyon with a geologist is enough to convince a skeptic of the liveliness of rock and to permanently dislocate an egocentric sense of time. The Canyon isn’t simply there, it’s happening — as are the raw young Rockies, our angular, adolescent mountains. Amid the multiplicity of rhythms on this earth, the 70-year life spans we make so ponderous are the briefest sparks — but they seem lovelier known that way, like the flights of butterflies across granite, like an eyelash sweeping a cheek.

My life is important, just as each separate moment in time with its unique, unrepeatable composition is important — but no more so. Like a frame in a movie, it is part of the rest. So am I. The brutalizing of earth by one of its species is like the violation of a tree by one of its branches: grotesque, foul as a cancer.

Pride seems to be a kind of cancer. Like cells that lose their place in the scheme and grow to kill the body that supports them, we tend with any encouragement at all to move to center stage and focus the world picture around ourselves. Pretty soon, we’re IT and the rest is props. The result — for an individual or a species — is death. Emotionally, politically, historically, we die of unreality.

Imagining the conflicting forces in great explorers, Alexander Eliot groups humility, intuition and energy as interdependently creative, and lumps pride with fanaticism and decay. The pattern holds for the professor who refuses to listen to new voices in the world and insists on his “canon,” the Western-white-male-approved culture, as the world’s sole wisdom; for the woman with a madonna complex who justifies herself with motherhood and devours her children; for all of us insofar as we are blindly narcissistic, gazing only at our own faces wherever we look.

What mysterious self-destruct button is built into our characters? Blake said once that Shame is Pride’s cloak, and George Bernard Shaw paraphrased him through a character who refused to be intimidated by conventional opinion and admitted cheerfully to being shameless. The reverse idea seems as likely, that Pride is the shield worn by Shame. Coming to this life partial and disconnected — ashamed of our inadequacies — what can we do but paint ourselves bigger and bigger to fill the ego’s black hole and keep the aliens at bay?

Albert Schweitzer mystified his friends when he decamped for Lamborene to practice primitive medicine in the bush, but he knew what he was doing in rejecting the assumption that a European was more valuable than an African. He perceived the beauty and pathos in all things destined to change when he pleaded for “Reverence for Life” in its multiple forms, and his path was a pattern for the serious business of living. Ours not to judge and rank; ours but to make contact, do what we can.

When we learn that there are no aliens, and that fellow travelers on this small spaceship of ours — those other aborigines, wild flowers and fierce birds — complete us, then Pride will join the dinosaur and other outmoded figures of history. If it doesn’t we’re in big trouble.

ENVY

WHEN THE COLORS OF THE LOVELY EARTH DIM

“Not poppy, nor mandraqgora,/Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,/ Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep/ Which thou ow’dst yesterday. . . .”

So gloated Iago as he plotted to destroy Othello with the most visceral and poisonous form of envy, sexual jealousy. Iago’s “green-ey’d monster” crawls in the blood, bitter as cyanide, corrupting sleep, food, thought and every human contact.

When I am jealous, the colors of the lovely earth dim, the family of man fades to a pale cutout, and the suspect lover sheds all humanity and shrinks to a single function, one act of stabbing betrayal. What was whole and real is shattered and shadowy because my domain is violated and cheapened by an intruder. Someone else has access to those warm eyes and hands, those invitations and familiar responses. An outsider has breached my magic circle of power and safety. Killing would be easy.

For most of us, envy isn’t like that. It’s a momentary twinge, wistful:

“That profile would make me loved. If I had her face. . .”

“You’ve gotta be dishonest to make that kind of money without working. . .”

“How come their children can hold jobs and still make the Dean’s List?”

“She must be crazy, walking away from that beautiful place and her nice husband when she’s middle-aged and has nothing of her own. What’s she got to look happy about?”

These are passing afflictions, sinking spells amid the contradictory demands of lives out of focus. Perhaps all of us have known such petty defeats — or nearly all. A journalist said once of Lady Antonia Frazer that she is entirely without malice. It may be so. Beautiful, warm and gifted, she may never have known this bitter fruit of envy, affirmation’s flip side. Affirmation celebrates and emulates; envy says, “If I can’t own it, destroy it.”

It happened in Victorian drawing rooms, as women in creaking stays cut up the reputations of their lovelier sisters along with the tea cake. It happens now in boardrooms, where the old-boy network makes short shrift of bright interlopers with challenging ideas.

Some people are born to envy as others are born to humor or devotion. A scenario:

Paul Stone in his 40s still hates his high school teachers. A man with large eyes and a small mouth, he works grimly at a job he doesn’t respect, pays his bills on time, tries to see that his three children behave responsibly, is doggedly faithful to his wife, Ann. He avoids undue social activity, preferring to putter in his house surrounded by his family. He lends his tools to less fortunate friends and is patient with their idiosyncrasies.

When Paul and Ann are drawn into the orbit of new neighbors, the Cutlers, a warm, witty couple with a flair for profitable investment and spontaneous plans, Paul is secretly flattered to be included in their circle. He eats authentic Peruvian arroz con pato at their table and watches silently as Tom and Betsy Cutler regale dinner guests with stories in which perfectly ordinary people, animals and places suddenly glow with beguiling eccentricity. Paul takes in the hilarity and the wonder, and he listens as others seek advice from the Cutlers and warm themselves in the household’s laughter. He complains later to his wife that dinner is too late and the food too spicy.

Paul, Ann and their children are invited to join the Cutlers’ family excursions — impromptu picnics in a museum garden, weekend theater trips, ski weeks — but Paul usually resists Ann’s enthusiasm and declines. He’s too busy or the trip is too expensive.

When Paul’s daughter Margaret is accepted into a university writing program Paul can’t afford, Tom Cutler offers financial help. He can pass along information about a stock issue forbidden to him as a broker but legal for outsiders. Paul refuses to consider a deviation from the investment advice of the firm that served his father well. Ann pleads, but he lashes out, “Why should I trust Cutler? He can afford to risk losing money — and I can’t.” Ann sells her grandmother’s jewelry to send Margaret to school.

The Stones don’t see much of the Cutlers for a season. Late one misty summer night, Margaret Stone flings into her parents’ bedroom. The Cutlers are away for the weekend and their son Steve has totaled the car and been charged with drunk driving and resisting arrest. They must come at once — he’s in jail. Paul wants to let him stay there overnight: “He’ll learn something.” Margaret insists; he wasn’t drunk, he had two beers and hit an oil slick in the fog. The cop was nasty. When Steve tried to protest, he got slugged and taken away.

The Stones drive to the station and Paul smiles at Ann. “You think they’re God’s gift to the world. Well, it looks as though they make some mistakes too. I wouldn’t leave my kids home to crack up the cars while I’m off socializing.” He pays the bail and enjoys walking down to the Cutlers’ on Monday night to present his account. He savors his small victories — like the news that his old English teacher was killed riding her bike to school on Earth Day.

Why does a man loathe the thing he needs most? Like a mole burrowing away from the sun, he shuts out beauty, lightness and wit. He can’t see the courage and deft timing of another man as a gift but merely as a reproach to his own gracelessness. His black-hole ego devours all light and reflects none. His kind abounds in families from Cinderella’s on, clogging the world’s arteries with resentment.

Why, on the other hand, does another man, decent and ordinary, live among his glittering charismatic brothers with no envy at all?

Why doesn’t Horatio turn on Prince Hamlet when he has the chance? Hamlet sees Horatio as one whose passion and judgment are so well mixed “that they are not a pipe for fortune’s finger/To sound what stop she please.” The man is somehow possessed of the psychic soil that nurtures magnanimity.

Such generous and empathetic good will toward enviable spirits does not blossom from self-denial or conscious martyrdom. The more we give up for other people, the more self-congratulatory and carping critical of them we often become — the more separate and incomplete.

If psychiatry is right and our lonely fragmented egos mourn our expulsion from the Eden of the womb, possibly the only road to integration — wholeness of holiness — is intense involvement in the wider universe we inherit. A liberal upbringing — liberal in the old sense of free and generous — may convince us that love exists powerfully, may give each the courage to know and identify with others in wider and wider circles of connection to the things around us — to music, manatees and men.

I don’t fear and hate the possessor of the beautiful profile if I know and like the woman and feel that she is beautiful for us all. The dancer who moves with the fluidity of cats and dolphins celebrates bodies, mine with her own. I and my craft are larger for the poet who can write rings round me.

A friend, a musician who died recently of AIDS, wrote to me that facing death wasn’t so difficult because his experience made him feel part of all life, something large and enduring. He had lived idiosyncratically and hilariously, in total disregard of Opinion, responsible only to art and friendship. I think he died without regrets and without enemies.

People said they envied his free spirit, but what they meant was, they loved it. He was a window on a possible world, defying tax collectors on behalf of us all. Some may think he got caught in the end, but he didn’t.

SLOTH

THE DEADLIEST OF THEM ALL

Sloth is the laughable sin. Picture the sluggish zoological specimen hanging inert from a tree. Picture its human counterparts: a man with a beer belly snoozing mountainously in his hammock, a woman in a housedress popping mid-morning chocolates and watching soaps. There’s no glamour; the lapses are undramatic, unheroic, petty and suburban, and seemingly innocuous. But Sloth is the one to watch, the most insidious, the deadliest of them all.

Sloth means settling for less, making an inner deal. Everyone has known it (everyone but Ralph Nader), the laziness that allows one to toss the beer can out the car window, leave politics to somebody else, or accept lust as a substitute for love. It is Sloth, not the medieval villain Covetousness, that prepares the way for all the other sins.

Compulsive activity, no matter how virtuous seeming, can be a mask for laziness. Witness the writer who answers all the calls on his message tape, gets ahead on his bills and balances his checkbook, fixes the back step, even scrubs out the old coffee pot so breakfast won’t taste like petroleum — instead of sitting down at the typewriter to face the inner music. Sloth is avoiding The Thing I Am Supposed to Do, whatever that is. It is Not-painting the picture, Not-examining the marriage, Not-listening to the children. It is washing the car instead of writing the hard condolence letter.

How do I know what I am supposed to do? It is probably the thing which requires most effort and which I would most like to avoid. Hauling garbage looks onerous until I need to come up with a story; then trash cans become weightless, and so does anything else that gets me out of my snarled sentence, out into a wordless world of birdsong. I can kid myself that my garden needs weeding. Something in me knows I am playing hooky, avoiding Real Life.

Psychiatrist Scott Peck opens his best-known book with the words, “Life is difficult.” He isn’t merely observing life, he is defining it, but those of us lucky enough to have basic survival issues resolved don’t believe what he says — that to be alive as a human being involves difficulty in the same way it involves breathing. If we did, we would never park our children in front of television sets. We would understand that labor-saving devices don’t exist to assure us ease but to free up time for pursuits more difficult than manual work, challenges like confronting this life’s nature and living with someone else.

Like most religious thinkers, Peck sees truthfulness and love as the two avenues to a fully conscious humanity. Mental health itself, he says, depends on “an ongoing process of dedication to reality at all costs.” What a prescription! Everyone knows that reality is our least appealing option — at its best paradoxical, at the worst hopelessly incomprehensible, full of nasty surprises like entropy and relativity, not to mention other people.

The most we can do is to take the tiny piece of reality we have at hand and chew it carefully till we begin to like the taste of ambiguity. Possibly it will yield us immunity to the viruses of snap judgment and sanctimony. When reality is a loveless childhood and arrested emotional development, who wouldn’t prefer a wistful fantasy to the bleak recognition of one’s own loneliness and inadequacy? What wife wouldn’t prefer to strike a sanctimonious attitude and blame a husband’s wandering interest on midlife crisis and male immaturity than to examine her own egocentric isolation? When the truth seems to have no light or warmth in it, we need a cozy lie.

Unluckily, not only is there no gain without pain, but there actually is no painlessness, gain or not. Certain suffering belongs to us, is so endemic that when we distort the real world to avoid it, we incur a substitute pain of equal intensity but without the vital, liberating charge a brush with reality would generate. The neurotic substitute is shadow pain, obscuring real needs, confusing and separating us from ourselves, others and serious living. It tangles the demands on us, warps and reduces us. We become ineffectual bores. The easy road leads into miserable terrain, but we drift on to it to keep our backs to the wind.

It is easier to be fanatic than honestly curious. That is why lunatic cults and religious quacks succeed, along with simplistic political rhetoric. It is easier to anesthetize the heart’s deep hunger for truth — with a drink, a drug, a sentimental evasion — than to probe. If we avoid heavy thinking and squint a little, we can see our bad luck as someone else’s fault, our good luck as earned, greed as entitlement, desire as sanction, cruelty as discipline, another person as a cipher or a tool — nearly any twisted pattern that comforts us for the moment.

Then we become solemn instead of serious. Russell Baker made the distinction several years ago in a column for The New York Times Magazine. Serious acts are generated naturally by authentic desire; they well up irrepressibly, like the acts of young children, and are in no way calculated for effect. Solemn acts are phony, distorted by self-importance. Poker, according to Baker, is serious. Jogging is solemn.

Few adults rest comfortably enough in their skins to be honest for long, so seriousness is a minority attitude. Mahatma Gandhi was serious. The British Empire was solemn. It takes rare courage and energy to cut through the fog of shame and societal expectation to one’s own vision, and ignore the howls of outrage all reality elicits. It is much easier to be solemn.

Anything is easier than breaking the habit of searching for ease. Most of us don’t try until we are too paralyzed or agonized by pain that we can’t understand to continue. Then, in desperation, we may elect the knife, turn to the terrible surgery of truth for release.

The other steep trek into adult humanity is love, as rigorous as truth and wedded to it. Scott Peck defines love as “the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth.” “Extend” — there’s that painful growing again. Love’s opposite, evil, is the “exertion of political power or coercion to avoid extending one’s self for spiritual growth.” In between the two lie innumerable pale apathies, gelatinous dissolutions of will that simply allow the emotions to disengage when the fun seems over, another person demands to be subject rather than object, or change is in order.

Love of a partner may require a life-shift and the embrace of something new. A new need may accompany the new look around her waistline and in her eye as she rounds 50. The tempo may shift as he decides to search for the man he hoped once to become. Sloth declines to listen and evades responsibility, taking refuge in a thicket of cliches that cut off discussion.

Love of self may suddenly demand study or committed action, a more disciplined structuring of time, and an end to a secure job or to chatty problem-swapping friends. Sloth excuses itself solemnly from any decisive move; it adheres to fuzzy, specious loyalties, and brightens its listlessness with four fingers of bourbon.

Sloth is the crime of the unhungry spirit against itself, a progressive atrophying of the psyche that bleaches and flattens all experience. In its desolation, it empties our lives of their potential seriousness and of their lovely, peculiar stories.

THE EIGHTH DEADLY SIN

Wallace Stevens calls us “unhappy men in a happy world.” Alexander Eliot sees the earth as “a heaven defiled” and wonders why, “instead of singing, we scratch in the dirt and scold,” bogged down in wistfulness for the vanished happiness of Eden.

Where are the wings that can give us enough loft for real life? Our comic spirits lend them to us — our Molieres, Chaplins, Lewis Carrolls, Woody Allens, Maya Angelous — those architects of human proportion who take a long, clear look at the abyss and laugh.

We love them because they see us with delight, not horror. Shared laughter connects us like shared endeavors and lightens the baggage we carry. Ray Bradbury thought hoots and roars of laughter could cut the Devil himself down to size. A doctor cured his cancer with laughter. Traveling light, we free up energy to pay the price for joy and learn to live.

A student of mine wrote recently, “To be a free spirit means to be inspired by life and the imagination.” Inspiration needs room, unballasted space in the mind and heart. Maybe Humorlessness is the eighth deadly sin, coming into its own in this century of a million deadly fundraisers.

Meanwhile, leaving our happy insights behind us in schoolrooms and movie theaters, we are missing out. If the visionaries of the world have been right all along, time is room, not a road. It exists in its totality relative to this expanding universe.

The picture is beyond our minute capacity to see, but glimmers of this weird reality — that all of history is right now — penetrate our poetry and mathematics. What if Genesis is inspired prophecy and all our nostalgia is for the paradise we are about to lose?

Perhaps the fruit of knowledge, our self-conscious separation from earth, dims awareness. Perhaps the human tragedy is not to recognize heaven when we see it, or know that Eden is here and now.

Brooke Hearn is a writer and high school English teacher who lives in Baltimore.

Credit: Source link