The most astonishing and accomplished sequence in Richard Flanagan’s Question 7 arrives near the book’s end, as he describes the near-death experience that inspired his first novel, Death of a River Guide, published in 1994.

It reads as if Flanagan has spent the book winding up, gathering the strength to find an angle of entry into that formative trauma. With propulsive confidence, he details the hours spent trapped under a kayak, being battered and pressed by the Franklin River’s tumultuous waters, brushing up against death, perhaps briefly succumbing, before being rescued and returned, transformed, to the world of the living.

The irony, however, of this sequence’s brilliance, is that it clarifies how certain aspects of the book that precedes it are oddly hesitant.

Review: Question 7 – Richard Flanagan (Knopf)

Question 7 begins with an epigraph from a review of Moby-Dick, printed in an 1851 edition of the Hobart Town Mercury, speculating about the generic ambiguity of Herman Melville’s masterwork. The reviewer is baffled as to whether they are reading “history, autobiography, gazetteer, tragedy, romance, almanac, melodrama or fantasy”.

The reader is thus introduced to the refusal of Question 7 to neatly inhabit a single genre, and its occasional efforts to trouble the distinction between truth and fabrication.

The formal experimentation appears to derive from Flanagan’s anxiety that autobiography is necessarily fictitious. The desire to document one’s life accurately, he suggests, is made foolish by the ephemerality of language, the unreliability of memory, and the unaccountable contingencies of history.

Notably, the narrator of Question 7 – who seems, despite the formal evasiveness, to be Richard Flanagan – refers to Death of a River Guide as “another novel”, suggesting this was the category he had in mind when writing Question 7. Much of the book is, however, essayistic and, for what it’s worth, it is categorised on the publisher’s website as “non-fiction prose”.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville

Who loves longer?

The question around which Question 7 orbits is taken from an early Chekhov story titled “Questions Posed by a Mad Mathematician” (Flanagan omits the title).

Penguin Random House

In Chekhov’s version, a description of a train travelling between stations at specified times, written in the style of a tricky question of arithmetic, ends instead with a metaphysical query: “Who is capable of loving longer, a man or a woman?”

Flanagan’s version, returned to throughout the book, is: “Who loves longer?”

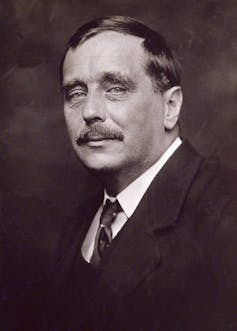

In considering this question, Flanagan traces a path from H.G. Wells’ affair with Rebecca West to Wells’ 1914 novel The World Set Free, the invention of the atomic bomb, and the bombing of Hiroshima, which brought about the end of his father’s internment in a Japanese prison camp.

Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, a key figure in the bomb’s creation, reads Wells and, comprehending the potential destructive reality of such a weapon, conceives of its scientific possibility. Flanagan explains:

Without Rebecca West’s kiss H.G. Wells would not have run off to Switzerland to write a book in which everything burns, and without H.G. Wells’s book Leo Szilard would never have conceived of a nuclear chain reaction. Poetry may make nothing happen, but a novel destroyed Hiroshima and without Hiroshima there is no me and these words erase themselves and me with them.

Flanagan thus intertwines his personal narrative with a kind of historical fiction. The impulse to understand how he is implicated in the broad sweep of historical catastrophe is understandable, but pays off inconsistently. In one instance, for example, he imagines Szilard taking a bath (Flanagan tells us Szilard was an inveterate bather) and contemplating the possibility of Wells’ apocalyptic fictions becoming reality:

As he lay back in his tub that autumnal London morning, Leo Szilard wondered why the forecasts of writers sometimes prove to be more accurate than those of scientists.

U.S. Department of Energy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In the acknowledgements, Flanagan admits Szilard’s bath is “pure fancy”. The problem is that it reads like fancy, more caricature than characterisation, adding nothing of substance. This is particularly evident when contrasted with Flanagan’s descriptions of members of his own family, whom he typically brings to striking, vivid life.

The bath sequence is followed by a passage in which Szilard is struck by the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction while watching traffic lights change in central London, a fact to which the physicist attested that is startling enough and needs no embellishment.

Similarly, a chapter in which Flanagan attempts to get inside the heads of West and Wells during their first encounter, which led to their affair and lifelong entanglement, feels fabricated and flimsy:

And so as their monologues began duelling, dancing, fighting and playing together, tumbling like dangerous kittens, she began enjoying herself.

And yet there are moments of startling historical insight. Fascinatingly, terrifyingly, Flanagan explains that the systematic genocide of Tasmania’s Aboriginal people by British colonists was the stimulus for Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds. Flanagan thus connects the nuclear destruction that terminated the war with Japan, where his Tasmanian father was imprisoned, to the systematic extermination of the first peoples in his native Tasmania.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: The War of the Worlds

Throughout all this, he continues to ask: “Who loves longer?” I was never sure what exactly this meant. Flanagan reads the question as being

Like so much of what Chekhov wrote … about how the world from which we presume to derive meaning and purpose is not the true world.

Undercutting this, the power Question 7 possesses is sourced almost entirely from those moments when Flanagan appears to be trying his hardest to tell the truth. It is an incomprehensible paradox, never quite reconciled, that Flanagan seems convinced of the insufficiency of language, yet equally convinced of a novel’s role in bringing us to the edge of apocalypse.

“All words,” he writes,

are at best transitory and soon enough become archaic, ceasing to belong to language at all and instead becoming the property of data sets that after a further time return only dead URL links, so many 404 errors.

His conclusion? Writers are “no more than dancing shoes sliding between the dancer and the floor”.

There are several philosophical asides like this, expressing anxiety about the language’s failure to rightly communicate meaning. In this picture, there is a true world unavailable to us, and a false one determined by our words. Yet these conceptions of truth and falsity are also linguistically determined, so Flanagan’s notion of insufficiency, hanging on language, in the thrall of a commitment to some essential yet unavailable reality, undoes itself from the inside out.

The central oddness of the book is that the power of this generalised question, fictitiously posed by a mad mathematician, is far less potent than the urgency conjured by Flanagan’s humblest reminiscences. Recounting a cherished childhood memory of capturing and riding a Clydesdale bareback, experiencing the thrill of risking and resisting a fall, Flanagan writes, a touch awkwardly:

It was a time of wonder and all things had the shape of miracles. And like a miracle, no evidence that it ever happened remains.

George Charles Beresford, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite his doubts, Flanagan presents us with the evidence that it did in fact happen, the form of his testimony, his memory. If neither memory nor testimony is evidence of anything, then I’m not sure how we are to make sense of ourselves. Flanagan is presenting a binary view of the world, where the fallibility of memory and language throws our identities into utter crisis.

This is happily undermined by the vibrant energy with which Flanagan tells us of the people he has loved.

The most moving and intelligent parts of Question 7 are the least concerned with the grand fluctuations of world history. They describe Flanagan’s family: his ornery grandmother, known as Mate, regretfully outliving her husband and friends, “condemned to survive on her children’s charity”; his father, disgruntled by Flanagan’s mother’s culinary adventurousness in serving meat and four veg, requesting an end to this “modern food” and a return to meat and three. He recounts a trip to Japan where he meets his father’s erstwhile captors, and describes the death of his mother, the unbearable beauty of friends and family gathering around her in the final days.

Flanagan is at his least convincing when philosophising about the purpose and capacity of writing, as when he makes this baffling claim that the book itself does not bear out:

the only writing that can have any worth confounds time and stands outside of it, swims with it and flies with it and dives deep within it, seeking the answer to one insistent question: who loves longer?

A generous interpretation of this belief is that the best writing raises questions that are impossible to answer. But there are many types of productive ambiguity. Mightn’t there be other formulations, other dispositions, with which we can understand ourselves, others, and literature?

Read more:

Review: Richard Flanagan’s The Living Sea of Waking Dreams considers griefs big and small

That’s life

Question 7 owes a particular debt to Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, another novel that forges a complex relationship with autobiography and contends with the legacies of destruction wrought by the Allies during the second world war.

As Vonnegut meditatively repeats “So it goes” whenever a death is mentioned in his novel, Flanagan repeats the decidedly less poetic “That’s life” a handful of times throughout the book when the spectre of death is conjured.

There are numerous repetitions of this kind – some effective, others less so. For instance, Flanagan twice writes unhelpfully that

Experience is but a moment. Making sense of that moment is life.

Repetition is used more elegantly to reckon with the shifting understanding of one’s parents that comes with ageing. Flanagan tells of his father returning from the unspeakable horrors of a wartime prison camp, taking a train trip around Tasmania:

Perhaps he wanted to see people and places he had thought he would never see again. Perhaps it was an immeasurable comfort to him to be allowed to sit in their homes, their kitchens, their lounges, their backyards and say little or nothing, warmed by the human goodness of others, to be astonished by the small everyday acts of kindness too easily dismissed as everyday.

Near the book’s end, Flanagan writes of his return to the ordinary world after his near-drowning, seeing places and people he thought he would never see again:

It was such a comfort to be allowed to sit in their homes, I sat in their small kitchens, their tired lounges, their blighted backyards and said little or nothing, warmed by the immense human goodness of others. I was astonished by the small everyday acts of kindness too easily dismissed as everyday.

The repetition conveys the ways we follow and resist our parents, the ways we forever comprehend them anew as we grow towards and beyond the age they were when we were born. Through language, through writing, despite his reservations, Flanagan begins to understand and begins to be understood.

Credit: Source link